The Siege of Troy - Appendices

Summary of the Iliad

At the opening of the poem, the Greeks have already besieged Troy for nine years in vain; they are despondent, homesick, and decimated with disease. They had been delayed at Aulis by sickness and a windless sea; and Agamemnon had embittered Clytemnestra, and prepared his own fate, by sacrificing their daughter Iphegenia for a breeze. On the way up the coast, the Greeks had stopped here and there to replenish their supplies of food and concubines; Agamemnon had taken the fair Chryseis, Achilles the fair Briseis. A soothsayer now declares that Apollo is withholding success from the Greeks because Agamemnon has violated the daughter of Apollo's priest, Chryseis. The King restores Chryseis to her father, but, to console himself and point a tale, he compels Briseis to leave Achilles and take Chryseis' place in the royal tent. Achilles convokes a general assembly, and denounces Agamemnon with a wrath that provides the first word and recurring-theme of the Iliad. He vows that neither he nor his soldiers will any longer stir a hand to help the Greeks. (I-II)

We pass in review the ships and tribes of the assembled force, and (III) see bluff Menelaus engaging Paris in single combat to decide the war. The two armies sit down in a civilized truce; Priam joins Agamemnon in solemn sacrifice to the gods. Menelaus overcomes Paris, but Aphrodite snatches the lad safely away in a cloud and deposits him, miraculously powdered and

perfumed, upon his marriage bed. Helen bids him return to the fight, but he counter proposes that they "give the hour to dalliance." The lady flattered by desire, yields. (IV) Agamemnon declares Menelaus the victor, and the war is apparently ended; but the gods, in imitative council on Olympus, demand more blood. Zeus votes for peace, but withdraws his vote in terrified retreat when Hera, his spouse, directs her speech upon him. She suggests that if Zeus will agree to the destruction of Troy she will allow him to raze Mycenae, Argos, and Sparta to the ground. The war is renewed; many a man falls pierced by arrow, lance, or sword, and "darkness enfolds his eyes." (V) The gods join in the merry slicing game; Ares, the awful god of war, is hurt by Diomed's spear, "utters a cry as of nine thou-sand men" and runs off to complain to Zeus. (VI) In a pretty interlude the Trojan leader Hector, before rejoining the battle, bids good-by to his wife Andromache. "Love," she whispers to him, "thy stout heart will be thy death; nor hast thou pity of thy child or me who shall soon be a widow." Then he strides down the causeway to battle and (VII) engages Ajax, King of Salamis, in single combat. They fight bravely, and separate at nightfall with exchange of praise and gifts — a flower of courtesy floating on a sea of blood. (VIII) After a day of Trojan victories, Hector bids his warriors rest. (IX) Nestor, King of Elian Pylus, advises Agamemnon to restore Briseis to Achilles; he agrees and promises Achilles half of Greece if he will rejoin the siege; but Achilles continues to pout. (X) Odysseus and Diomed make a two-man sally upon the Trojan camp at night and slay a dozen chieftains. (XI) Agamemnon leads his army valiantly, is wounded, and retires. Odysseus, surrounded, fights like a lion; Ajax and Menelaus cleave a path to him and save him for a better life. (XII-XIII) When the Trojans advance to the walls that the Greeks have built about their camp (XIV), Hera is so disturbed that she resolves to rescue the Greeks. Oiled, perfumed and ravishingly gowned, and bound with Aphrodite's aphrodisiac girdle, she seduces Zeus to a divine slumber while Poseidon helps the Greeks to drive the Trojans

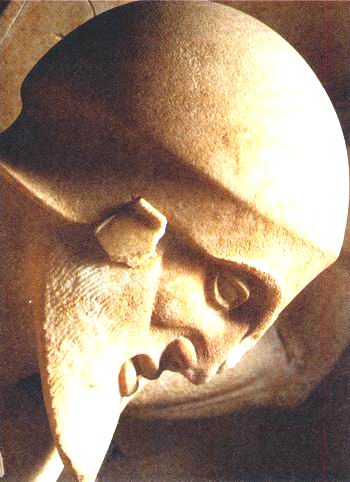

Agamemnon's funeral mask

back. (XV) Advantage fluctuates; the Trojans reach the Greek ships, and the poet rises to a height of fervid narrative as the Greeks fight desperately in a retreat that must mean death. (XVI) Patroclus, beloved of Achilles, wins his permission to lead Achilles' troops against Troy; Hector slays him, and (XVII) fights Ajax fiercely over the body of the youth. (VIII) Hearing of Patroclus' death, Achilles at last resolves to fight. His goddess-mother Thetis persuades the divine smithy,

Hephaestus, to forge for him new arms and a mighty shield. (XIX) Achilles is reconciled with Agamemnon, (XX) engages Aeneas, and is about to kill him when Poseidon rescues him. (XXI) Achilles slaughters a host of Trojans. The gods take up the fight: Athena lays Ares low with a stone, and when Aphrodite, going for a soldier tries to save him, Athena knocks her down with a blow upon her fair breast. Hera cuffs the ears of Artemis; Poseidon and Apollo content themselves with words.- (XXII) All Trojans but Hector fly from Achilles; Priam and Hecuba counsel Hector to stay behind the walls, but he refuses. Then suddenly, as Achilles advances on him, Hector takes to his heels. Achilles pursues him three times around the walls of Troy; Hector makes a stand, and is killed. (XXIII) In the sub-siding finale of the drama, Patroclus is cremated with ornate ritual. Achilles sacrifices to him many cattle, twelve captured Trojans, and his own long hair. The Greeks honor Patroclus with games, and (XXIV) Achilles drags the corpse of Hector behind his chariot three times around the pyre. Priam comes in state and sorrow to beg for the remains of his son. Achilles relents, grants a truce of twelve days, and allows the aged king to take the cleansed and anointed body back to Troy.

from Will Durant — The Life of Greece

Before the siege of Troy

Troy's strong walls were reputedly built with the help of the gods Poseidon and Apollo. The Trojans were further favored by the gift of the Palladium, an image of Pallas-Athene which fell to them from heaven. By the time Priam and Hecuba ruled, Troy was a prosperous center of civilization in Asia Minor. Priam and his wife had many children, but Hector was the noblest and most beloved. Prior to the birth of their son Paris, his mother dreamed of a firebrand. That dream was given the interpretation that the child about to be born would

be the cause of Troy's destruction. To save their city, the parents decided to send the babe to be left on Mt. Ida. As fate would have it, the child was rescued and then raised by kind shepherds. He became a hearty and strong youth with a reputation for his good looks.

After the Iliad

Even after the death of Hector, the Trojans continued to fight sending out fresh heroes to take his place. One was the Amazon queen Penthesilea, who was killed by Achilles. It was said that when he removed her helmet and saw her beauty, that he stood fixed in sorrow at the fate of so fair a face. Memnon, the Egyptian, arrived to assist Troy, but he too was felled by Achilles. Finally it was the hero's time to die. The god Poseidon guided an arrow of Paris to the one vulnerable spot in Achilles' body: the heel by which his mother held him when he dipped him into the immortalizing water of the river Styx. Still Troy did not yield. Achilles' son, Pyrrus, entered the fray, and the poisoned arrows of Philoctetes were brought to be used. With one of them Paris met his death. An oracle said that Troy would not fall as long as it had possesion of the Palladium, a sacred statue. Odysseus and Diomede resolved to steal it, but the Trojans continued to resist. At last Odysseus hit upon a plan. Under his guidance they fabricated an immense wooden horse which moved on wheels. The belly of it was hollow and large enough to hold twelve armed men. This' giant horse with its hidden cargo of twelve soldiers was left outside the walls of Troy and the Greeks pretended to leave their camps for home. The Trojans debated about what to do with the horse and finally, considering it to be a gift from the gods, decided to make a breech in their massive walls and drag it inside their city — fatal mistake. While the Trojans slept that night, the Greeks hidden within the horse climbed out, signaled their fellow Greeks and opened the gates for them to

The Trojan Horse (painting by Tiepolo)

enter. The Greeks stormed the city killing many of the men and capturing the women and children. Priam was stabbed to death by Achilles' son. The only Trojan hero to escape was Aeneas, who later, according to legend, went on to found Rome.

The princes of Greece sailed away, each with a share of the spoils, but many did not have a joyful homecoming. Some were ship-wrecked or driven astray in stormy weather. Some came back to find themselves forgotten or supplanted. Most ill-fated was King Agamemnon, who was stabbed to death by his wife and her lover. She had never forgiven her husband for sacrificing their daughter in return for gaining fair winds for sailing. Most famous of the returning heroes is Odysseus, whose travels and eventual homecoming are recounted in the Odyssey, the other of Homer's two great epics.

Achilles: the archetypal Greek hero

The Greek conception of a hero does not always run parallel to our modern or yogic conceptions. Achilles himself gives a brief definition of a hero when he remembers his heroic and now deceased friend, Patroclus: "... he longed for his man-hood, his gallant heart— what rough campaigns they'd fought to an end together, what hardships they had suffered, cleaving their way through wars of men and pounding waves at sea."

The Greek hero is fully a man and enters into the activities of ancient manhood — war, plunder, adventure — with a happy heart. He worships the gods in the prescribed way, honoring them outwardly by burning thighs of oxen, and inwardly with an attitude of humility and reverence, always recognizing his own place in the divine scheme of things and recognizing that whatever powers are at his disposal are ultimately god-given.

The Iliad gives us the striking example of such a man —Achilles, who abides in the human dimension of life, but is pulled godward by unseen forces (called gods by the Greeks). Achilles fulfills his social obligations, earns honor by his physical courage and prowess as a warrior, reveres the gods and listens to their guidance. He is able to express pity and mercy and friendship to his foe when the gods demand it of him.

In Homer's description of the events of the siege of Troy we are presented with a vast field of vital education: war. In the experience of war a man is tested to see the strength of his courage and heroism. His nature is honed by gigantic forces (human and divine) that work to bring out noble human possibilities. The struggles between the Greeks and the Trojans, between Achilles and his king Agamemnon, revolve around issues of power and honor (two of the usual passions that dominate man's lower vital). From one point of view Achilles is a god-like hero who allows himself to be overpowered by enormous vital passions: pride, anger, grief and finally a blood-

thirsty revenge. In spite of these indisputably lower movements, a transformation is brought about in him when he finally follows the divine command to "check your rage" and opens his heart in a spirit of mercy and compassion to his enemy. The climax of the Iliad is not Troy's defeat (in fact that event is not even included in Homer's tale), it is the reconciliation of two of its most powerful antagonistic figures. This may not be a verifiable historical fact, but it is a poetic fact of the highest" order. Homer allows us to enter into a spirit and atmosphere which passed away centuries ago, but still has the power to uplift us because it expresses the universal human possibility of rising above the lower nature.

According to Greek mythology, Achilles, the greatest warrior of Agamemnon's army at Troy, was the son of the mortal king Peleus and the immortal sea-nymph Thetis. In one tale of his childhood, it is related that his mother dipped him into the river Styx to thus immortalize him and to make him invulnerable in war. Apparently she was interrupted in her task, the result being that he was invulnerable with the exception of the heel by which she held him. (Hence our modem day expression "Achilles heel" which means a weak point.) Achilles was educated by Chiron, the elder centaur known for his deep wisdom. An oracle in his father's court predicted that Achilles would die fighting in Troy. To escape this prophecy his mother disguised him as a girl and sent him to live with the daughters of a neighboring king. However, another soothsayer pro-claimed that Troy could not be taken without Achilles' help, so the Greeks sent wily Odysseus to search for him. When discovered by Odysseus, Achilles was quite willing to join the Greek army and headed his father's Myrmidon troops when the fleet embarked for Troy.

By examining closely several descriptions of the hero Achilles, his nature may be better understood. First of all, he is renowned for his physical strength, boldly describing him-self as "swift and excellent... brilliant." He furthermore pro-claims that "no man is my equal among the bronze-armed

Acheans." Homer gives an example of his strength in comparison to normal men: "A single pine beam held the gates [to Achilles' camp] and it took three men to ram it home, three to shoot the immense bolt back and spread the doors — three average men. Achilles alone could ram it home himself."

Others concur with Achilles' glowing self-evaluation. He is described by Odysseus, another of the great Greek heroes as: "brave... godlike... greatest of Acheans, greater than I, stronger with spears by no small edge."

Beyond mere physical courage and strength was his fearless poise in the face of his own immanent death. He had known from childhood that he has the power to choose the course of his life:

"Mother tells me,

The immortal goddess Thetis with her glistening feet

That two fates bear me on to the day of death.

If I hold out here and I lay siege to Troy,

My journey home is gone, but my glory never dies.

If I voyage back to the fatherland I love,

My pride, my glory dies...

True, but the life that's left me will be long."

As he is about to kill a young Trojan in battle he utters this speech about himself:

"So friend, you die also. Why all this clamour about it? Patroclus is also dead, who was better by far than you are. Do you not see what a man I am, how huge, how splendid and born of a great father and the mother who bore me immortal? Yet, even I have also my death and my strong destiny, and there shall be a dawn or an afternoon or a noontime when some man in the fighting will take the life from me also either with a spear cast or an arrow flown from a bowstring."

His death is forecast more than once and each time he meets

the prospect with a calm courage. In the next passage, he has a conversation with his horses which have been divinely inspired by the goddess Hera to warn him of his impending death:

"But the day of death already hovers near and we are not to blame, but a great god is and the strong force of fate..."

He answers:

"Why prophesy my doom? Don't waste your breath. I know,„ ell I know — I am destined to die here, far from my dear father, far from my mother. But all the same I will never stop till I drive the Trojans to their bloody fill of war."

Achilles is loved by the gods. It is known that he will die in the siege of Troy, but the gods will ensure his glory among men and his immortal fame. They enhance his own innate prowess as a warrior with their power. One of the greatest Trojans, Aeneas, comments:

"That is why no mortal can fight Achilles... at every foray one of the gods goes with him, beating back his own death. Even without that power his spear flies, straight to the mark, never stops; not till it bores clean through some fighter's flesh."

The gods, too, have complimentary words to say about Achilles.

Poseidon advises Aeneas not to fight against Achilles, saying:

"Aeneas — what god on high commands you to play them adman? Fighting against Achilles' overwhelming fury —both a better soldier and more loved by the gods."

Iris calls him "brilliant Achilles". Zeus, chief of the Gods, says:

Ajax carrying the body of Achilles

(painted by Exekias, c. 540 BC)

"Achilles is no madman, no reckless fool, not the one to defy the gods' Commands. Whoever begs his mercy he will spare with all the kindness in his heart."

Usually Achilles is on good terms with the gods and is favored by them, but at one point in the battle he quarrels with Zeus' river, the Scamander. The river begs him to desist from his bloodshed as his clear waters are being polluted:

"Stop Achilles! Greater than any man on earth,

Greater in outrage too —

For the gods themselves are always on your side!

But if Zeus allows you to kill off all the Trojans,

Drive them out of my depths at least, I ask you,

Out on the plain and do your butchery there.

All my lovely rapids are crammed with corpses now,

No channel in sight to sweep my currents out to sacred

sea—

I'm choked with corpses and still you slaughter more,

You blot out more! Leave me alone, have done —

Captain of armies, I am filled with horror!"

When Achilles is almost overwhelmed, by the river's fury, Poseidon and Pallas Athene encourage him with these words:

"Courage, Achilles! Why such fear, such terror?

Not with a pair like us to urge you on — gods-in-arms

Sent down with Zeus's blessings, I and Pallas Athene.

It's not your fate to be swallowed by a river:

He'll subside, and soon — you'll see for yourself...

But once you've stripped away Prince Hector's life,

Back to the ships you go! We give you glory —

Seize it in your hands!"

Achilles is an irresistible and bloodthirsty fighter. In Homer's description of the fight to the death with Hector we can

feel the savage intensity of Achilles as a warrior.

"...but Achilles was closing on him now like the god of war, the fighter's helmet flashing, over his right shoulder shaking the Pelian ash spear, that terror, and the bronze around his body flared like a raging fire or the rising blazing sun. Hector looked up, saw him, started to tremble, nerve gone, he could hold his ground no longer, he left the gates behind and away he fled in fear — and Achilles went for him, fast, sure of his speed as the wild mountain hawk, the quickest thing on wings, launching smoothly, swooping down on a cringing dove and the dove flits out from under, the hawk screaming over the quarry, plunging over and over, his fury driving him down to break and tear his kill — so Achilles flew at him, breakneck on in fury with Hector fleeing along the walls of Troy, fast as his legs would go... So Hector could never throw Achilles off his trail, the swift racer Achilles — time and again he'd make a dash for the Dardan Gates (safety), trying to rush beneath the rock-built ramparts, hoping men on the heights might save him, somehow, raining spears but time and again Achilles would intercept him quickly, heading him off, forcing him out across the plain and always sprinting along the city side him-self... And Achilles charges, too, bursting with rage, barbaric, guarding his chest with the well-wrought blazoned shield, head tossing his gleaming helmet, four horns strong and the golden plumes shook that the god of fire drove in bristling thick along its ridge. Bright as that star amid the stars in the night sky, star of the evening, brightest star that rides the heavens, so fire flared from the sharp point of the spear Achilles brandished high in his right hand, bent on Hector's death, scanning his splendid body — where to pierce it best?"

Achilles on the battlefield is a personification of martial violence, as this passage vividly illustrates:

"Achilles now

Like inhuman fire raging on through the mountain gorges

Splinter-dry, setting ablaze big stands of timber,

The wind swirling the huge fireball left and right —

Chaos of fire — Achilles storming on with brandished spear

Like a frenzied god of battle trampling all he killed

And the earth ran black with blood. Thundering on,

On like oxen broad in the brow some field hand yokes

To crush white barley heaped on a well-laid threshing floor

And the grain is husked out fast by the bellowing oxen's hoofs —

So as the great Achilles rampaged on, his sharp-hoofed stallions

Trampled shields and corpses, axle under his chariot splashed with blood,

Blood on the handrails sweeping round the car,

Sprays of blood shooting up from the stallions' hoofs

And churning, whirling rims — and the son of Peleus

Charioteering on to seize his glory, bloody filth

Spattering both strong arms, Achilles' invincible arms."

Achilles is not only a fierce warrior; his nature has another aspect too — that of a refined mind and emotions, qualities much admired by the ancient Greeks. He is a devoted and faithful friend to Patroclus, his childhood companion. When this friend is killed in battle and comrades bring him the painful news, Achilles is overwhelmed with grief:

"A black cloud of grief came shrouding over Achilles.

Both hands clawing the ground for soot and filth,

He poured it over his head, fouled his handsome face

And black ashes settled onto his fresh clean war-shirt.

Overpowered in all his power, sprawled in the dust,

Achilles lay there, fallen...

Tearing his hair, defiling it with his own hands...

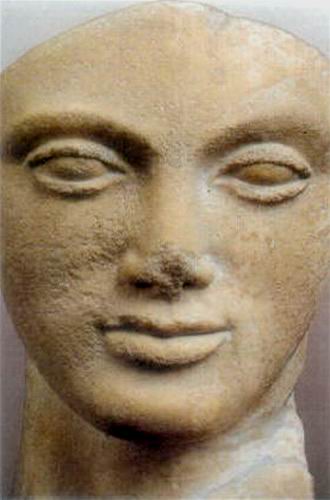

Dying warrior

(detail from a pediment sculpture, temple of Aphaea, c. 500 BC)

Antilochus kneeling near, weeping uncontrollably,

Clutched Achilles' hands as he wept his proud heart out—

For fear he would slash his throat with an iron blade.

Achilles suddenly loosed a terrible, wrenching cry..."

His devotion to his friend and the pain of his death lead him to set aside his prideful anger, heal his quarrel with his king and re-enter the battle to take a bloody revenge.

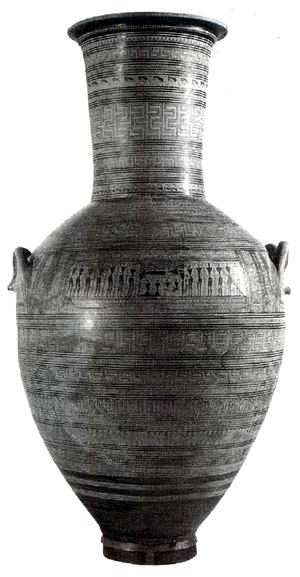

This amphora was originally placed as a tomb marker over a grave. A scene of a funeral is painted on it. (760-750 BC)

"Enough. Let bygones be bygones. Done is done.

Despite my anguish I will beat it down,

The fury mounting inside me, down by force.

Now, by god, I can call a halt to my anger —

It's wrong to keep on raging, heart-inflamed forever.

Quickly, drive our long-haired Acheans to battle now!"

When the Greeks send an embassy to persuade the proud hero to re-join the fight, Homer gives us a brief but telling glimpse of Achilles at home:

"Reaching the Myrmidon shelters and their ships,

They found him there, delighting his heart now,

Plucking strong and clear on the fine lyre —

Beautifully carved, its silver bridge set firm —

He won from the spoils when he razed Eetion's city.

Achilles was lifting his spirits with it now,

Singing the famous deeds of fighting heroes."

Achilles is a man of refinement. He entertains his guests with every courtesy and prepares the meal for them with his own hands. Later on, in Patroclus' honor he organizes and presides over funeral games, showing respect for each of the Greek heroes and sorting out the ego clashes that arise during the competitions with a gentlemanly tact. However, his fierce devotion to his friend's memory leads him to extreme actions:

"Farewell, Patroclus, even there in the House of Death!

Look — all that I promised once I am performing now:

I've dragged Hector here for the dogs to rip him raw —

And here in front of your flaming pyre I'll cut the throats

Of a dozen sons of Troy in all their shining glory,

Venting my rage on them for your destruction!"

No delineation of Achilles' character would be complete without a mention of his cardinal defects: pride and anger.

Homer's first lines tell us of the wrath of Achilles and of its disastrous consequence: the destruction of so many great fighters. However, his anger and its results serve a higher purpose, and this, too, Homer makes clear from the very beginning of the poem:

"Sing to me, Muse, of the wrath of Achilles Pelidean,

Murderous, bringing a million woes on the men of Achaea,

Many the mighty souls whom it drove down to Hades,

Souls of heroes and made of their bodies booty for vultures,

Dogs and all birds; so the will of Zeus was wholly accomplished

Even from the moment when they two parted in strife and anger,

Peleus' glorious son and the monarch of men Agamemnon."

{Translation of lines 1-7 by Sri Aurobindo}

To understand the nature of Achilles' pride and anger, it is useful to look a little more closely at the nature of the quarrel between Achilles and his king, Agamemnon. The episode begins when Achilles responds to the problem at hand — the fact that Greek soldiers are dying of a pestilence — with calm reasonableness. He consults a soothsayer and then in public assembly tries to persuade his king to follow the prescribed advice, i.e. to return the captured slave girl to her father, Apollo's priest. The king replies by asking Achilles to give up his own slave girl to replace the one that will have to be returned. The modern reader must understand the extent to which this is insulting behavior on the part of the king. Throughout the Iliad Achilles is acknowledged without question as the greatest Greek fighter. He has fought long and hard on the king's behalf and has fairly won his booty. To be deprived of it is to be deprived of the honor and glory of which

it is the outer sign. Their quarrel quickly escalates to the point where Agamemnon delivers this hostile speech:

"You (and he refers to Achilles) — I hate you most of all the warlords

Loved by the gods. Always dear to your heart,

Strife, yes, and battles, the bloody grind of war.

What if you are a great soldier? That's just a gift of god.

Go home with your ships and comrades, lord it over Your Myrmidons!

You are nothing to me — you and your overweening anger."

Being addressed in such a way by his king awakens a fury in Achilles' heart and he struggles to control it, finally receiving divine help:

"Anguish gripped Achilles.

The heart in his rugged chest was pounding, torn...

Should he draw the long sharp sword slung at his hip,

Thrust through the ranks and kill Agamemnon now?

Or check his rage and beat his fury down?"

Hera and Athena rush to intervene, demanding self-control and obedience from their favored hero:

"Down from the skies I come to check your rage —

Stop this fighting, now. Don't lay hand to sword.

And I tell you this — and I know it's the truth —

One day glittering gifts will lie before you,

Three times over to pay for all his out rage.

Hold back now. Obey us both."

Achilles is quick to respond, ready to surrender his small will to that greater Divine Will:

"I must — when the two of you hand down commands, Goddess,

A man submits though his heart breaks with fury.

Better for him by far. If a man obeys the gods

They're quick to hear his prayers."

In a way, the rest of the Iliad is about how circumstances arrange themselves so that Achilles fulfills this initial promise of obedience to the Divine Will. Achilles withdraws himself and his men from the siege and says he will not rejoin the battle until the Achaeans are disgraced. Several friends make attempts through reason to change his mind, arguing that the Trojans would be overjoyed to see the king and his finest warrior angry with each other, but for a time nothing persuades the hero. The Greeks begin to suffer terrible losses in battle, so much so that Achilles' friend Patroclus begs to be allowed to fight in Achilles' stead to hearten the Greek troops in their hour of need. Achilles permits his friend to don his own heavenly armor, little suspecting that the outcome of this brave venture will be Patroclus' death at the hands of Prince Hector. Achilles is overcome with grief when he realizes that he has bought his own glory and honor with the death of his beloved friend. This pushes him to take revenge by re-entering the battle. His rage, still furiously ignited, is now at least spending itself to help the Greek cause, the one favored by Zeus. He rises in public assembly and says:

"For years to come, I think

They will remember the feud that flared between us both.

Enough. Let bygones be bygones. Done is done.

Despite my anguish I will beat it down,

the fury mounting inside me, down by force.

Now, by god, I call a halt to my anger—

It's wrong to keep on raging, heart inflamed forever.

Quickly drive our long-haired Achaeans to battle now!"

This god-like man stands as an example to all Greeks —indeed to humanity — as one who subdues his lower nature and puts himself in the hands of the gods to work out a divine purpose. In a way he may be compared to Arjuna who is asked to make a similar surrender. Both offer their capacities as skillful and courageous warriors to be used by a force greater than their own that works in the lives of men to work out inscrutable will. At the deepest level, the true hero is the manor woman who is able to make the complete surrender to the Divine.

A brief comparison of Achilles and Arjuna

Nowadays it is an undisputed fact that the Mahabharata and the Iliad are two of the world's greatest epics. In these times of a growing global consciousness it may be of interest for students and teachers of East and West to compare the two splendid heroes that are introduced to world civilization in these epics.

Although both poems are literary expressions of a particular people, it is clear that they are founded on actual historical events that have assumed great importance in the life of mankind. The Mahabharata gave us the great spiritual teaching of the Gita which it is said will yet liberate mankind; the Iliad led to the creation of Hellas and modern western civilization. Both epics have put before us heroes who upheld the ancient warrior code of life and battle. Arjuna and his Greek counter-part, Achilles, are representative men — master-men in the making who have been chosen by the gods and given a divine work. It is, in both epics, the warrior's dharma to battle for the right, to lay down his life, or to win a glorious victory for a just cause. Both men are conscious of a divine mission in life and in various ways are the constant recipients of divine guidance Arjuna directly from Lord Krishna, and Achilles, as directly from Zeus, Athena, and other Greek deities.

The seers who wrote these epics attributed semi-divine parentage to both heroes. Arjuna is said to be the son of the god Indra and Achilles has a divine mother: Thetis. These heroes have received special training in the art of warfare, and have even been given divine armor and weapons that give the man extraordinary power on the battlefield. There, none can equal them and they display a remarkable physical prowess and an unwavering physical courage. Circumstances around them have been arranged so that they are called to fight for a just cause. Each one aims for a great achievement in battle, and to each a victory is given. Achilles is eventually killed by the Trojans, but his re-entry into the field of battle assures their eventual victory, for so it has been foretold. Arjuna is part of the victorious army on the field of Kurukshetra. Krishna has assured him that he and his brothers are destined to win.

Both of these personalities exhibit heroic qualities of the highest order. Besides physical skills and even great physical beauty, both men are known to have qualities of the heart. Each one displays a loyalty that is inspiring: Arjuna serves his brothers, mother, and wife in a most loyal fashion; Achilles is devoted to his friend Patroclus and makes every effort to avenge his death so that he can be given a fitting funeral. Both men are said to be noble in bearing and are recognized as heroes by the men around them. They are refined in their tastes —not merely brute soldiers. Achilles played the lyre and sang; Arjuna was enough of a dancer to train a princess in that graceful art.

But even more interesting is the way these men are shown to respond to a divine guidance. Arjuna faces doubt and faint-heartedness about his chosen mission at the commencement of the great war. He turns to Krishna for help and soon there after his mind is illumined and he again takes up his mission — but this time with a deeper understanding of its hidden values. The great message "Abandon all dharmas and take refuge in Meal one". Armed with its Light Arjuna takes his stance in battle

on the side of a right trying to establish itself in the midst of a darkness that has overtaken the entire Kshatriya race. Achilles also must face the limitations of his lower nature. He is struck by pride and anger and deserts his king when his help is most needed. He has to be prodded by the gods and by circumstances to re-direct that anger so that he can re-enter the fray, and finally to check it completely at the order of the gods. He does not reach the spiritual heights described in the Gita. His. surrender takes longer. He clings to grief and anger until he gets the direct command from Zeus to return Hector's body to the Trojan King Priam so that it may be honorably buried. At that moment he rises to his greatest height and achieves a harmony with his enemy.

The heroes of both epics may be further illumined by deeper comparison of their natures. Such a reflection will widen the understanding between the peoples of East and West and can be a valuable aid to teachers around the world.

The fight between Hector and Achilles

Related Books

- Alexander the Great

- Arguments for The Existence of God

- But it is done

- Catherine The Great

- Danton

- Episodes from Raghuvamsham of Kalidasa

- Gods and The World

- Homer and The Iliad - Sri Aurobindo and Ilion

- Indian Institute of Teacher Education

- Joan of Arc

- Lenin

- Leonardo Da Vinci

- Lincoln Idealist and Pragmatist

- Marie Sklodowska Curie

- Mystery and Excellence on The Human Body

- Nachiketas

- Nala and Damayanti

- Napoleon

- Parvati's Tapasya

- Science and Spirituality

- Socrates

- Sri Krishna in Brindavan

- Sri Rama

- Svapnavasavadattam

- Taittiriya Upanishad

- The Aim of Life

- The Crucifixion

- The Good Teacher and The Good Pupil

- The Power of Love

- The Siege of Troy

- Uniting Men - Jean Monnet