The Good Teacher and The Good Pupil - To Parents Teachers And Pupils

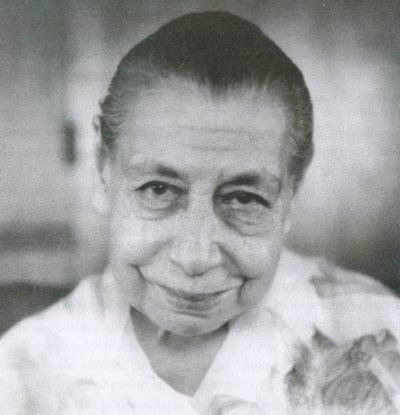

The Mother

To Parents Teachers and Pupils

The Mother was born in Paris on February 21, 1878, in a very materialistic, upper middle class family. She completed a thorough education of music, painting and higher mathematics. A student of the French painter Gustave Moreau, she befriended the great Impressionist artists of the time. She later became acquainted

with Max Theon, an enigmatic character with extraordinary occult powers who, for the first time, gave her a coherent explanation of the spontaneous experiences' occurring since her childhood, and who taught her occultism during two long visits to his estate in Algeria.

In 1914 she visited the city of Pondicherry, which was at that time a French colony, in South India, and met Sri Aurobindo. She returned permanently to Pondicherry in 1920 via Japan and China, and when Sri Aurobindo "withdrew" from outer contact in 1926 to devote himself to the "supramental yoga", she collaborated with him and at the same time organized and developed the Ashram.

The Mother is the author of several books. Prayers and Meditations and On Education are her short but important books. She presided over the Sri Aurobindo International Centre of Education in which hundreds of students studied. The Mother herself taught classes, and her talks to the children constitute a series of nine books entitled Entretiens or Questions and Answers. She also wrote stories and short plays which were staged under her direction. Her plays are symbolic and bring out through meaningful dialogues a profound message.

In 1958, eight years after Sri Aurobindo's departure, she in turn withdrew to her room to come to terms with the problem of evolution. From 1958 to 1973, she slowly uncovered the "Great Passage " to the next species and a new mode of life in matter, and narrated her extraordinary exploration to her closest confidant, Satprem. This tremendous document of 6,000 pages in thirteen volumes is calledMother's Agenda. It is a document of experimental evolution, and goes to the heart of the question of our times. For, whatever the appearances, mankind is not at the end of a civilization but at the end of an evolutionary cycle. Are we going to find the passage to the next species... or perish? In 1968, Mother founded Auroville and declared in its Charter that its aim was, inter alia, to be a site of perpetual education and youth that never ages.

We present here a few extracts from the Mother s book On Education. The selected extracts give valuable insights into what parents and teachers should do in regard to education and children. They also give valuable advice to those who are seeking the discovery of the true self and to achieve higher and higher degrees of perfection.

(To Know Oneself and Control Oneself)

An aimless life is always a miserable life.

Everyone of you should have an aim. But do not forget that on the quality of your aim will depend the quality of your life.

Your aim should be high and wide, generous and disinterested; this will make your life precious to yourself and to others.

But whatever your ideal, it cannot be perfectly realised unless you have realised perfection in yourself.

To work for your perfection the first step is to become conscious of yourself, of the different parts of your being and their respective activities. You must learn to distinguish these different parts one from the other, so that you may find out clearly the origin of the movements that occur in you, the many impulses, reactions and conflicting wills that drive you to action. It is an assiduous study which demands much perseverance and sincerity. For man's nature, specially his mental nature, has a spontaneous tendency to give a favourable explanation for whatever he thinks, feels, says and does. It is only by observing these movements with great care, by bringing them, as it were, before the tribunal of our highest ideal, with a sincere will to submit to its judgment, that we can hope to educate in us a discernment which does not err. For if we truly want to progress and acquire the capacity of knowing the truth of our being, that is to say, the one thing for which we have been really created, that which we can call our mission upon earth, then we must, in a very regular and constant manner, reject from us or eliminate in us whatever contradicts the truth of our existence, whatever is in opposition to it. It is thus that little by little all the parts, all the elements of our being, could be organised into a homogeneous whole around our psychic centre. This work of unification demands a long time to be brought to some degree of perfection. Hence, to accomplish it, we must arm ourselves with patience and endurance, with a determination to prolong our life as far as it is necessary for the success of our endeavour.

As we pursue this labour of purification and unification, we must at the same time take great care to perfect the external and instrumental part of our being. When the higher truth will manifest, it must find in you a mental being supple and rich enough to be able to give to the idea seeking to express itself a form of thought

which preserves its force and clarity. This thought, again, when it seeks to clothe itself in words must find in you a sufficient power of expression so that the words reveal the thought and not deform it. And this formula in which you embody the truth should be made articulate in all your sentiments, all your willings and acts, all the movements of your being. Finally, these movements themselves should, by constant effort, attain their highest perfection.

All this can be realised by means of a fourfold discipline the general outline of which is given here. These four aspects of the discipline do not exclude each other, and can be followed at the same time, indeed it is better to do so. The starting-point

is what can be called the psychic discipline. We give the name "psychic" to the psychological centre of our being, the seat within of the highest truth of our existence, that which can know and manifest this truth. It is therefore of capital importance for us to become conscious of its presence within us, to concentrate on this presence and make it a living fact for us and identify ourselves with it.

Through space and time many methods have been framed to attain this perception and finally to achieve this identification. Some methods are psycho- logical, some religious, some even mechanical. In reality, everyone has to find out that which suits him best, and if one has a sincere and steady aspiration, a persistent and dynamic will, one is sure to meet in one way or another, externally by study and instruction, internally by concentration, meditation, revelation and experience, the help one needs to reach the goal. Only one thing is absolutely indispensable: the will to discover and realise. This discovery and this realisation should be the primary occupation of the being, the pearl of great price which one should acquire at any cost. Whatever you do, whatever your occupation and activity, the will to find the truth of your being and to unite with it must always be living, always present behind all that you do, all that you experience, all that you think.

A story-day in the Mother's class for children

To complete this movement of inner discovery, it is good not to neglect the mental development. For the mental instrument can be equally a great help or a great hindrance. In its natural state the human mind is always limited in its vision, narrow in its understanding, rigid in its conceptions, and a certain effort is needed to enlarge it, make it supple and deep. Hence, it is very necessary that one should consider everything from as many points of view as possible. There is an exercise in this connection which gives great suppleness and elevation to thought. It is as follows. A clearly formulated thesis is set; against it is opposed the antithesis, formulated with the same precision. Then by careful reflection the problem must be widened or transcended so that a synthesis is found which unites the two contraries in a larger, higher and more comprehensive idea.

Many exercises of the same kind can be undertaken; some have a beneficial

effect on the character and so possess a double advantage, that of educating the mind and that of establishing control over one's feelings and their results. For example," you must never allow your mind to judge things and people; for the mind is not an instrument of knowledge — it is incapable of finding knowledge — but it must be moved by knowledge. Knowledge belongs to a region much higher than that of the human mind, even beyond the region of pure ideas. The mind has to be made silent and attentive in order to receive knowledge from above and manifest it. For it is an instrument of formation, organisation and action. And it is in these functions that it attains its full value and real utility.

Another practice may be very helpful for the progress of the consciousness. Whenever there is a disagreement on any matter, such as a decision to take, or an act to accomplish, one must not stick to one's own conception or point of view. On the contrary, one must try to understand the other's point of view, put oneself in his place and, instead of quarrelling or even fighting, find out a solution which can reasonably satisfy both parties; there is always one for men of goodwill.

Here must be mentioned the training of the vital. The vital being in us is the seat of impulses and desires, of enthusiasm and violence, of dynamic energy and desperate depression, of passions and revolt. It can set in motion everything, build up and realise, it can also destroy and mar everything. It seems to be, in the human being, the most difficult part to train. It is a long labour requiring great patience, and it demands a perfect sincerity, for without sincerity one will deceive oneself from the very first step, and all endeavour for progress will go in vain. With the collaboration of the vital no realisation seems impossible, no transformation impracticable. But the difficulty lies in securing this constant collaboration. The vital is a good worker, but most often it seeks its own satisfaction. If that is refused, totally or even partially, it gets vexed, sulky and goes on strike; the energy disappears more or less completely and leaves in its place disgust for people and things, discouragement or revolt, depression and dissatisfaction. At these moments one must remain quiet and refuse to act; for it is at such times that one does stupid things and in a few minutes can destroy or spoil what one has gained in months of regular effort, losing thus all the progress made. These crises are of less duration and are less dangerous in the case of those who have established a contact with their psychic being sufficient to keep alive in them the flame of aspiration and the consciousness of the ideal to be realised. They can, with the help of this consciousness, deal with their vital as one deals with a child in revolt, with patience and perseverance showing it the truth and light, endeavouring to convince it and

awaken in it the goodwill which for a moment was veiled. With the help of such patient intervention each crisis can be changed into a new progress, into a further step towards the goal. Progress may be slow, falls may be frequent, but if a courageous will is maintained one is sure to triumph one day and see all difficulties melt and vanish before the radiant consciousness of truth.

Lastly, we must, by means of a rational and clear-seeing physical education, make our body strong and supple so that it may become in the material world a fit instrument for the truth-force which wills to manifest through us.

In fact, the body must not rule, it has to obey. By its very nature it is a docile and faithful servant. Unfortunately it has not often the capacity of discernment with regard to its masters, the mind and the vital. It obeys them blindly, at the cost of its own well-being. The mind with its dogmas, its rigid and arbitrary principles, the vital with its passions, its excesses and dissipations soon do everything to destroy the natural balance of the body and create in it fatigue, exhaustion and disease. It must be freed from this tyranny; that can be done only through a constant union with the psychic centre of the being. The body has a wonderful capacity of adaptation and endurance. It is fit to do so many more things than one can usually imagine. If instead of the ignorant and despotic masters that govern it, it is ruled by the central truth of the being, one will be surprised at what it is capable of doing. Calm and quiet, strong and poised, it will at every minute put forth effort that is demanded of it, for it will have learnt to find rest in action, to recuperate through contact with the universal forces the energies it spends consciously and usefully. In this sound and balanced life a new harmony will manifest in the body, reflecting the harmony of the higher regions which will give it the perfect proportions and the ideal beauty of form. And this harmony will be progressive, for the truth of the being is never static, it is a continual unfolding of a growing, a more and more global and comprehensive perfection. As soon as the body learns to follow the movement of a progressive harmony, it will be possible for it, through a continuous process of transformation, to escape the necessity of disintegration and destruction. Thus the irrevocable law of death will have no reason for existing any more.

As we rise to this degree of perfection which is our goal, we shall perceive that the truth we seek is made up of four major aspects: Love, Knowledge, Power and Beauty. These four attributes of the Truth will spontaneously express themselves in our being. The psychic will be the vehicle of true and pure love, the mind that of infallible knowledge, the vital will manifest an invincible power and strength and the body will be the expression of a perfect beauty and a perfect harmony.

Education

... The majority [of the parents], for various reasons, take very little thought of a true education to be given to children. When they have brought a child into the world, and when they have given him food and satisfied his various material wants by looking more or less carefully to the maintenance of his health, they think they have fully discharged their duty. Later on, they would put him to school and hand over to the teacher the care of his education.

There are other parents who know that their children should receive education and try to give it. But very few among them, even among those who are most serious and sincere, know that the first thing to do, in order to be able to educate the child, is to educate oneself, to become conscious and master of oneself so that one does not set a bad example to one's child. For it is through example that education becomes effective. To say good words, give wise advice to a child has very little effect, if one does not show by one's living example the truth of what one teaches. Sincerity, honesty, straightforwardness, courage, disinterestedness, unselfishness, patience, endurance, perseverance, peace, calm, self-control are all things that are taught infinitely better by example than by beautiful speeches. Parents, you should have a high ideal and act always in accordance with that ideal. You will see little by little your child reflecting this ideal in himself and manifesting spontaneously the qualities you wish to see expressed in his nature. Quite naturally a child has respect and admiration for his parents; unless they are quite unworthy, they will appear always to their children as demigods whom they will seek to imitate as well as they can.

With very few exceptions, parents do not take into account the disastrous influence their defects, impulses, weaknesses, want of self-control have on their children. If you wish to be respected by your child, have respect for yourself and be at every moment worthy of respect. Never be arbitrary, despotic, impatient, ill- tempered. When your child asks you a question, do not answer him by a stupidity or a foolishness, under the pretext that he cannot understand you. You can always make yourself understood if you take sufficient pains for it, and in spite of the popular saying that it is not always good to tell the truth, I affirm that it is always good to tell the truth, only the art consists in telling it in such a way as to make it accessible to the brain of the hearer. In early life, till he is twelve or fourteen, the child's mind is hardly accessible to abstract notions and general ideas. And yet you can train it to understand these things by using concrete images or symbols or parables. Up to a sufficiently advanced age and for some who mentally remain always children, a

The Mother giving a prize in the Playground

narrative, a story, a tale told well teaches much more than a heap of theoretical explanations.

Another pitfall to avoid: do not scold your child except with a definite purpose and only when quite indispensable. A child too often scolded gets hardened to rebuke and no longer attaches much importance to words or severity of tone. Particularly, take care not to rebuke him for a fault which you yourself commit. Children are very keen and clear-sighted observers: they soon find out your weaknesses and note them without pity.

When a child has made a mistake, see that he confesses it to you spontaneously and frankly; and when he has confessed, make him understand with kindness and affection what was wrong in his movement and that he should not repeat it. In any case, never scold him; a fault confessed must be forgiven. You should not allow any fear to slip in between you and your child; fear is a disastrous way to education:

invariably it gives birth to dissimulation and falsehood. Only an affection that is discerning, firm yet gentle and a sufficient practical knowledge will create bonds of trust that are indispensable for you to make the education of your child effective. And never forget that you have to surmount yourself always and constantly so as to be at the height of your task and truly fulfil the duty which you owe your child by the mere fact of your having brought him into existence.

Psychic and Spiritual Education

... The three lines of education — physical, vital and mental — deal with that which may be defined as the means of building up the personality, raising the individual out of the amorphous subconscious mass, making it a well-defined self- conscious entity. With psychic education we come to the problem of the true motive of life, the reason of our existence upon earth, the discovery to which life must lead and the result of that discovery: the consecration of the individual to his eternal principle. This discovery very generally is associated with a mystic feeling, a religious life, because it is religions particularly that have been occupied with this aspect of life. But it need not be necessarily so: the mystic notion of God may be replaced by the more philosophical notion of truth and still the discovery will remain essentially the same, only the road leading to it may be taken even by the most intransigent positivist. For mental notions and ideas possess a very secondary importance in preparing one for the psychic life. The important thing is to live the experience: for it carries its own reality and force apart from any theory that may precede or accompany or follow it, because most often theories are mere explanations that are given to oneself in order to have more or less the illusion of knowledge. Man clothes the ideal or the absolute he seeks to attain with different names according to the environment in which he is born and the education he has received. The experience is essentially the same, if it is sincere; it is only the words and phrases in which it is formulated that differ according to the belief and the mental education of the one who has the experience. All formulation is only an approximation that should be progressive and grow in precision as the experience itself becomes more and more precise and coordinated. Still, if we are to give a general outline of psychic education, we must have an idea, however relative it may be, of what we mean by the psychic being. Thus one can say, for example, that the creation of an individual being is the result of the projection, in time and space, of one of the countless possibilities latent in the Supreme Origin of all manifestation which, through the one and universal consciousness, is concretised in the law or the truth of an individual and so becomes by a progressive growth its soul or psychic being.

I stress the point that what I have said here in brief does not profess to be a complete exposition of the reality and does not exhaust the subject — far from it. It is just a summary explanation for a practical purpose so that it can serve as a basis for the education with which we are concerned.

It is through the psychic presence that the truth of an individual being comes into contact with him and the circumstances of his life. In most cases this presence acts, so to say, from behind the veil, unrecognised and unknown; but in some, it is perceptible and its action recognisable; even, in a few among these, the presence becomes tangible and its action quite effective. These go forward in their life with an assurance and a certitude all their own, they are masters of their destiny. It is precisely with a view to obtain this mastery and become conscious of the psychic presence that psychic education has to be pursued. But for that there is need of a special factor, the personal will. For till now, the discovery of the psychic being, the identification with it, has not been among the recognised subjects of education. It is true one can find in special treatises useful and practical hints on the subject, and also there are persons fortunate enough to meet someone capable of showing the path and giving the necessary help to follow it. More often, however, the attempt is left to one's own personal initiative: the discovery is a personal matter and a great resolution, a strong will and an untiring perseverance are indispensable to reach the goal. Each one must, so to say, chalk out his own path through his own difficulties. The goal is known to some extent; for, most of those who have reached it have described it more or less clearly. But the supreme value of the discovery lies in its spontaneity, its genuineness: that escapes all ordinary mental laws. And this is why anyone wanting to take up the adventure, usually seeks at first some person who has gone through it successfully and is able to sustain him and show him the way. Yet there are some solitary travellers and for them a few general indications may be useful.

The starting-point is to seek in yourself that which is independent of the body and the circumstances of life, which is not born of the mental formation that you have been given, the language you speak, the habits and customs of the environment in which you live, the country where you are born or the age to which you belong. You must find, in the depths of your being, that which carries in it the sense of universality, limitless expansion, termless continuity. Then you decentralise, spread out, enlarge yourself; you begin to live in everything and in all beings; the barriers separating individuals from each other break down. You think in their thoughts, vibrate in their sensations, you feel in their feelings, you live in the life of all. What seemed inert suddenly becomes full of life, stones quicken, plants feel and will and suffer, animals speak in a language more or less inarticulate, but clear and expressive; everything is animated with a marvellous consciousness without time and limit. And this is only one aspect of the psychic realisation. There are many others. All combine

in pulling you out of the barriers of your egoism, the walls of your external personality, the impotence of your reactions and the incapacity of your will.

But, as I have already said, the path to come to that realisation is long and difficult, strewn with traps and problems, and to face them demands a determination that must be equal to all test and trial. It is like the explorer's journey through virgin forest, in quest of an unknown land, towards great discovery. The psychic being is also a great discovery to be made requiring at least as much fortitude and endurance as the discovery of new continents. A few words of advice may be useful to one resolved to undertake it:

The first and perhaps the most important point is that the mind is incapable of judging spiritual things. All those who have written on Yogic discipline have said so; but very few are those who have put it into practice and yet, in order to proceed on the path, it is absolutely indispensable to abstain from all mental opinion and reaction.

Give up all personal seeking for comfort, satisfaction, enjoyment or happiness. Be only a burning fire for progress, take whatever comes to you as a help for progress and make at once the progress required.

Try to take pleasure in all you do, but never do anything for the sake of pleasure.

Never get excited, nervous or agitated. Remain perfectly quiet in the face of all circumstances. And yet be always awake to find out the progress you have still to make and lose no time in making it.

Never take physical happenings at their face value. They are always a clumsy attempt to express something else, the true thing which escapes your superficial understanding.

Never complain of the behaviour of anyone, unless you have the power to change in his nature what makes him act thus; and if you have the power, change him instead of complaining.

Whatever you do, never forget the goal which you have set before you. There is nothing small or big in this enterprise of a great discovery; all things are equally important and can either hasten or delay its success. Thus before you eat, concentrate a few seconds in the aspiration that the food you will take brings to your body the substance necessary to serve as a solid basis for your effort towards the great discovery, and gives it the energy of persistence and perseverance in the effort.

Before you go to bed, concentrate a few seconds in the aspiration that the sleep may restore your fatigued nerves, bring to your brain calmness and quietness, that

on waking up you may, with renewed vigour, begin again your journey on the path of the great discovery.

Before you act, concentrate in the will that your action may help, at least not hinder in any way, your march forward towards the great discovery.

When you speak, before the words come out of your mouth, concentrate awhile just long enough to check your words and allow those alone that are absolutely necessary and are not in any way harmful to your progress on the path of the great discovery.

In brief, never forget the purpose and the goal of your life. The will for the great discovery should be always there soaring over you, above what you do and what you are, like a huge bird of light dominating all the movements of your being.

Before the untiring persistence of your effort, an inner door will open suddenly and you will come out into a dazzling splendour that will bring to you the certitude of immortality, the concrete experience that you have lived always and always shall live, that the external forms alone perish and that these forms are, in relation to what you are in reality, like clothes that are thrown away when worn out. Then you will stand erect freed from all chains and instead of advancing with difficulty under the load of circumstances imposed upon you by nature, borne and suffered by you, if you do not want to be crushed under them, you can walk on straight and firm, conscious of your destiny, master of your life.

And yet this release from all slavery to the flesh, this liberation from all personal attachment is not the supreme fulfilment. There are other steps to climb before you reach the summit...

From Sri Aurobindo and the Mother on Education

(Pondicherry: 1982) pp. 89-95, 97-99 and 121-27.

Contemplation, Painting by Rolf, Auroville

Pictures credit

— RolfLieser, Auroville: p. 37, p. 44, p. 57, p. 66, p. 84, p. 108, p. 119, p. 124, p. 220, p. 236, p. 525 — Olivier Barot, Auroville: p. 24, p. 28, p. 40, p. 58, p. 78, p. 423 — G.N. Chaturvedi: p. 174, 177, 306, 308 — Rajendran, Auroville: p. 171 — Pino Marchese, Auroville: p. 21, p. 22, p 347, p. 363, p. 516 — Nathalie Nuber, Auroville: p. 368, p. 373, p. 406, p. 409, p. 411 — Lea, Auroville: p. 459, p. 461 — Shakti, Auroville: p. 484 — Bettina, Auroville: p. 120 — Auroville Archives, Auroville: p. 501 — Pavitra, Auroville: p. 513—Nehru Memorial Museum Library, New Delhi: p. 374, p. 383 — Paulo Freire Institute: p. 490, p. 507 — Maria Montessori Association Archives, Amsterdam: p. 345, 348— Pestalozzi Institute:

p. 260, p. 269, 272, p. 277 — Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust Archives, p. 514, p. 515, p. 520 — Editions Auroville Press Publishers: p. 495 — Jean-Louis Nou, Mathura Museum: p. 96 — Abanindranath Tagore: p. 60 — Nandalal Bose: p. 74, p. 75, p. 81

— Upendra Maharathi, National Gallery of Modern Arts, New Delhi: p. 93.

Related Books

- Alexander the Great

- Arguments for The Existence of God

- But it is done

- Catherine The Great

- Danton

- Episodes from Raghuvamsham of Kalidasa

- Gods and The World

- Homer and The Iliad - Sri Aurobindo and Ilion

- Indian Institute of Teacher Education

- Joan of Arc

- Lenin

- Leonardo Da Vinci

- Lincoln Idealist and Pragmatist

- Marie Sklodowska Curie

- Mystery and Excellence on The Human Body

- Nachiketas

- Nala and Damayanti

- Napoleon

- Parvati's Tapasya

- Science and Spirituality

- Socrates

- Sri Krishna in Brindavan

- Sri Rama

- Svapnavasavadattam

- Taittiriya Upanishad

- The Aim of Life

- The Crucifixion

- The Good Teacher and The Good Pupil

- The Power of Love

- The Siege of Troy

- Uniting Men - Jean Monnet