The Aim of Life - The World As I See It

The World as I see It

Introduction

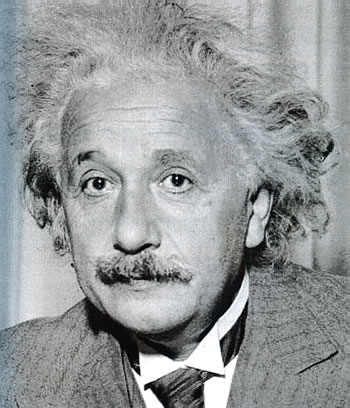

The man who became a world-famous scientist during his own lifetime did not do well at school. Albert Einstein's teacher wrote that he "could not be expected to make a success of anything. "1 In fact, he was late in learning to walk and did not speak fluently until he was nine. He later wrote that at the age of five he had been stirred by the mystery of a compass and he said:

At the age of twelve I experienced a second wonder of a totally different nature in a little book dealing with Euclidean plane geometry... Here were assertions, as for example, the intersection of the three altitudes of a triangle in one point, which though by no means evident — could nevertheless be proved with such certainty that any doubt appeared out of the question. This lucidity and certainty made an indescribable impression on me.2

Scientific books, especially books on mathematics, interested the young Einstein much more than school. By fifteen he gave up school altogether and went with his parents from Germany to Italy. Eventually, he applied for The Polytechnic in Zurich, only to fail the entrance examination. He studied for another year to make up for his deficiencies and passed the examination the following year. Still a

1. D. J. Raine, Albert Einstein and Relativity (Pitman Press, England, 1984), p. 17.

2. Carl Sagan, Broca's Brain (New York, Ballantine, 1980), p. 23.

mediocre student by academic standards, he relied on a friend's notes to get through. He greatly resented the examination system, the rigidity of the lecture system and the lack of freedom to study what interested him. This made him discontent, and he was unpopular with his teachers. Yet he managed to graduate with the help of his friend.

At the turn of the century, this friend's father got him a job as a Swiss civil servant (third class) at the Swiss Patent Office, when the more desirable research and university positions failed to materialise. He served there for seven years. During this period he married a fellow-student who had been the only one to fail the final examination in physics. They had two children and life appeared very ordinary in an undistinguished career. The Patent Office must not have been a very busy place, for Einstein recalled those years with nostalgia as a cloister where he could hatch "my most beautiful ideas ".

The "beautiful ideas" were contained in four papers that he published in 1905. Any of them would have been an impressive output of a life-time's work; so one can imagine the astonishment they created in the scientific world. The first demonstrated that light has particle as well as wave properties and explained the previously baffling photo-electric effect in which electrons are emitted by solids when irradiated by light. The second explored the nature of molecules by explaining the statistical "Brownian motion " of suspended small particles, and the third and fourth introduced the special theory of relativity and for the first time expressed the famous equation, E=mc2, which is so widely quoted. His theories were by no means readily accepted, and remained highly controversial if not rejected as incomprehensible or erroneous.

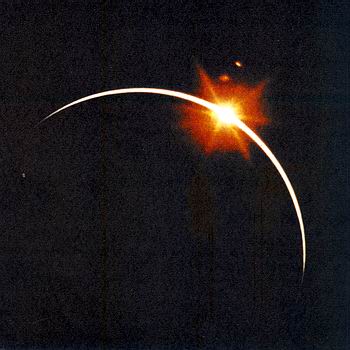

Nevertheless, these papers made him a name in the scientific community. He lectured at Bonn University and soon became a professor at Zurich University, and then in Prague, before receiving a professorship in Berlin which was then the centre of European science. Here Einstein remained for several years, devoting most, of his time to scientific research. When the first world war broke out in 1914, he quietly continued his work, but eventually suffered a breakdown from the tension of the war, lack of attention to his health and the breakup of his marriage. He was nursed back to health by his cousin, whom he later married. At the end of the war, British expeditions to Brazil and Africa established this German scientist as a world figure. The purpose of these expeditions was to photograph the eclipse of the sun from two distant points on the earth in order to test Einstein's theory that light is subject to gravitational forces. Sir Arthur Eddington took the measurements of the photographs and later said that this experience stayed in his memory as the greatest moment in his life. Fellows of the Royal Society rushed the news to one another:

Eddington by telegram to the mathematician Littlewood, and Littlewood in a hasty note to Bertrand Russell: "Einstein's theory is completely confirmed. "'

Einstein became a pacifist during the first world war and only his Swiss citizenship saved him from prison in Germany, while his friend Bertrand Russell was sent to jail in England for similar political ideals. During the period between the two world wars, Einstein's reputation grew as he travelled, lectured, and got extensive press coverage. He felt it was his responsibility to speak out his convictions and to lend his name to causes he found to be true. When the madness of Nazism overwhelmed Germany with the rise of Hitler in 1933, he had to flee Germany. When the Nazi terror spread across Europe, Einstein changed his pacifist views and told the conscientious objectors to fight in the war. The Nazis reacted by placing a price on his head and by denouncing his works, publicly burning his books and forcing scientists to speak against him. The great upsurge of anti-Semitism2 that came with Nazism caused Einstein to openly admit his Jewish origins. He even became interested in helping to form the state of Israel, while at the same time calling for an understanding of the Arab situation. In 1948 he was offered the Presidency of Israel, which he politely declined.

After leaving Germany, Einstein made his permanent home at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton University in the United States. It was there, during World War II, that his fellow scientists persuaded him to write to the President of the United States urging the development of the atomic bomb. There was a fear that Germany was already developing it. Einstein did not himself participate in the development of the bomb. It was later discovered that Germany would not succeed in making the bomb. Had he known this, Einstein said, he would never have supported its development by the United. States. He felt a great remorse for the advice he had given to the President. He attempted to unite scientists to stop all nuclear weapons development, but without success. Einstein continued in America to fight for the civil rights of all people and got his share of criticism during the era of Mc Carthyism,3 when people with Communist sympathies or leftist views lost their jobs or were brought to court for "un-American activities ".

His years at Princeton University saw no decrease in his intense research activities. Bronowski has fond memories of the great man lecturing in an old sweater

1. J. Bronowski, The Ascent of Man, London, Futura, 1984.

2. anti-Semitism: Sentiment against the Jews expressed in persecutions and restrictions which can be both racial and religious.

3. McCarthyism: McCarthy, Joseph R. 1908-1957. US Senator and Republican known for his vigorous attacks mainly on Communists and

subversives.

and carpet slippers with no socks, completely unconcerned with worldly success, respectability or conformity.1 But years of labour in pursuit of a unified field theory which would combine gravitation, electricity, and magnetism on a common basis seemed to have been unsuccessful.

Einstein's greatness allowed him to acknowledge his mistakes. In his model of the universe he did not follow his original calculations; had he done so, he might have made the same discovery that the American scientist Edwin Hubble made, namely, that the universe is expanding. Einstein referred to this as "the biggest blunder of my life". He did live to see his general theory of relativity incorporated as the principal tool for understanding the large scale structure and evolution of the universe, and he would have been delighted to see its vigorous application in current astrophysics.

Einstein himself had advanced the idea of probability as a way to avoid the need for two theories of light. The idea was taken up by others and was found to work. A whole new physics called " quantum physics " was developed to calculate the probabilities of events in the sub-atomic world. At this stage, however, Einstein disagreed with his colleagues. He could not reconcile himself with the idea of probability as an over-arching frame for science. As he put it: "God doesn't play dice with the cosmos. "2 His arguments against the new physics, however, did not stand. The last thirty years of his life were spent looking for an alternative to quantum physics, a work he felt had to be done even though there was small chance of success.

Einstein's death in 1955 concluded a lifetime of work in which he joined light to time and time to space, energy to matter, matter to space, and space to gravitation. These theories must be brought together, and after fifty years of work scientists still do not know how. Einstein opened new doors on the frontiers of knowledge that only a handful of people have walked through, but the effects of his discoveries are part of the world we all live in. He is a man who changed the world.

Einstein's life was filled with the tragedies of war and oppression, and he fought against them with all the power of his brilliant spirit; he never accepted the brutalities of his age but sought to overcome them through his life and work. In the selection from his writings that follows, he has told us of those principles which he believed in and which formed the basis of his pursuit of truth, whatever the cost or consequences.

1. J. Bronowski, Op. cit., p. 161.

2. Sagan, Op. cit., p. 35.

What an extraordinary situation is that of us mortals! Each of us is here for a brief sojourn; for what purpose he knows not though he sometimes thinks he feels it. But from the point of view of daily life, without going deeper, we exist for our fellowmen — in the first place for those on whose smiles and welfare our happiness depends, and next for all those unknown to us personally with whose destinies we are bound up by the tie of sympathy. A hundred times every day I remind myself that my inner and outer life depend on the labours of other men, living and dead, and that I must exert myself in order to give in the same measure as I have received and am still receiving. I am strongly drawn to the simple life and am often oppressed by the feeling that I am engrossing an unnecessary amount of the labour of my fellow-men. I regard class differences as contrary to justice and, in the last resort, based on force. I also consider that plain living is good for everybody, physically and mentally.

In human freedom in the philosophical sense I am definitely a disbeliever. Everybody acts not only under external compulsion but also in accordance with inner necessity. Schopenhauer's saying, that "a man can do as he will, but not will as he will", has been an inspiration to me since my youth up, and a continual consolation and unfailing wellspring of patience in the face of the hardships of life, my own and others. This feeling mercifully mitigates the sense of responsibility which so easily becomes paralysing, and it prevents us from taking ourselves and other people too seriously; it conduces to a view of life in which humour, above all, has its due place.

To inquire after the meaning or object of one's own existence or of creation generally has always seemed to me absurd from an objective point of view. And yet everybody has certain ideals which determine the direction of his endeavours and his

judgments. In this sense I have never looked upon ease and happiness as ends in themselves... such an ethical basis I call more proper for a herd of swine. The ideals which have lighted me on my way and time after time given me new courage to face life cheerfully, have been Truth, Goodness, and Beauty. Without the sense of fellowship with men of like mind, of preoccupation with the objective, the eternally unattainable in the field of art and scientific research, life would have seemed to me empty. The ordinary objects of human endeavour — property, outward success, luxury — have always seemed to me contemptible.

My passionate sense of social justice and social responsibility has always contrasted oddly with my pronounced freedom from the need for direct contact with other human beings and human communities. I set my own pace and have never belonged to my country, my home, my friends, or even my immediate family, with my whole heart; in the face of all these ties I have never lost an obstinate sense of detachment, of the need for solitude — a feeling which increases with the years. One is sharply conscious, yet without regret, of the limits to the possibility of mutual understanding and sympathy with one's fellow-creatures. Such a person no doubt loses something in the way of geniality and light-heartedness; on the other hand, he is largely independent of the opinions, habits, and judgments of his fellows and avoids the temptation to take his stand on such insecure foundations.

My political ideal is that of democracy. Let every man be respected as an individual and no man idolized. It is an irony of fate that I myself have been the recipient of excessive admiration and respect from my fellows through no fault, and no merit, of my own. The cause of this may well be the desire, unattainable for many, to understand the one or two ideas to which I have with my feeble powers attained through ceaseless struggle. I am quite aware that it is necessary for the success of any complex undertaking that one man should do the thinking and directing and in general bear the responsibility. But the led must not be compelled, they must be able to choose their leader. An autocratic system of coercion, in my opinion, soon degenerates. For force always attracts men of low morality, and I believe it to be an invariable rule that tyrants of genius are succeeded by scoundrels. For this reason I have always been passionately opposed to systems such as we see in Italy and Russia today. The thing that has brought discredit upon the prevailing form of democracy in Europe today is not to be laid to the door of the democratic idea as such, but to lack of stability on the part of the heads of governments and to the impersonal character of the electoral system. I believe that in this respect the United States of America have found the right way. They have a responsible President who is elected

Albert Einstein

for a sufficiently long period and has sufficient powers to be really responsible. On the other hand, what I value in our political system is the more extensive provision that it makes for the individual in case of illness or need. The really valuable thing in the pageant of human life seems to me not the State but the creative, sentient individual, the personality; it alone creates the noble and the sublime, while the herd as such remains dull in thought and dull in feeling.

This topic brings me to that worst outcrop of the herd nature, the military system, which I abhor. That a man can take pleasure in marching in formation to the strains of a band is enough to make me despise him. He has only been given his big brain by mistake; a backbone was all he needed. This plague-spot of civilisation ought to be abolished with all possible speed. Heroism by order, senseless violence, and all the pestilent non-sense that goes by the name of patriotism — how I hate them! War seems to me a mean, contemptible thing: I would rather be hacked in pieces than take part in such an abominable business. And yet so high, in spite of everything, is my opinion of the human race that I believe this bogey would have disappeared long ago, had the sound sense of the nations not been systematically corrupted by commercial and political interests acting through the schools and the Press.

The fairest thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the fundamental emotion which stands at the cradle of true art and true science. He who knows it not and can no longer wonder, no longer feel amazement, is as good as dead, a snuffed- out candle. It was the experience of mystery — even if mixed with fear — that engendered religion. A knowledge of the existence of something we cannot penetrate, of the manifestations of the profoundest reason and the most radiant beauty, which are only accessible to our reason in their most elementary forms — it is this knowledge and this emotion that constitute the truly religious attitude; in this sense, and in this alone, I am a deeply religious man. I cannot conceive of a God who rewards and punishes his creatures, or has a will of the type of which we are conscious in ourselves. An individual who should survive his physical death is also beyond my comprehension, nor do I wish it otherwise; such notions are for the fears or absurd egoism of feeble souls. Enough for me the mystery of the eternity of life, and the inkling of the marvellous structure of reality, together with the single-hearted endeavour to comprehend a portion, be it ever so tiny, of the reason that manifests itself in nature.

Good and Evil

It is right in principle that those should be the best loved who have contributed most to the elevation of the human race and human life. But, if one goes on to ask who they are, one finds oneself in no inconsiderable difficulties. In the case of political, and even of religious leaders, it is often very doubtful whether they have done more good or harm. Hence I most seriously believe that one does people the best service by giving them some elevating work to do and thus indirectly elevating them. This applies most of all to the great artist, but also in a lesser degree to the scientist. To be sure, it is not the fruits of scientific research that elevate a man and enrich his nature, but the urge to understand, the intellectual work, creative or receptive. It would surely be absurd to judge the value of the Talmud, for instance, by its intellectual fruits.

The true value of a human being is determined primarily by the measure and the sense in which he has attained to liberation from the self.

Society and Personality

When we survey our lives and endeavours we soon observe that almost the whole of our actions and desires are bound up with the existence of other human beings. We see that our whole nature resembles that of the social animals. We eat food that others have grown, wear clothes that others have made, live in houses that others have built. The greater part of our knowledge and beliefs has been communicated to us by other people through the medium of language which others have created. Without language our mental capacities would be poor indeed, comparable to those of the higher animals; we have, therefore, to admit that we owe our principal advantage over the beasts to the fact of living in human society The individual, if left alone from birth, would remain primitive and beastlike in his thoughts and feelings to a degree that we can hardly conceive. The individual is what he is and has the significance that he has not so much in virtue of his individuality, but rather as a member of a great human society, which directs his material and spiritual existence from the cradle to the grave.

A man's value to the community depends primarily on how far his feelings, thoughts, and actions are directed towards promoting the good of his fellows. We

call him good or bad according to how he stands in this matter. It looks at first sight as if our estimate of a man depended entirely on his social qualities.And yet such an attitude would be wrong. It is clear that all the valuable things, material, spiritual, and moral, which we receive from society can be traced back through countless generations to certain creative individuals. The use of fire, the cultivation of edible plants, the steam engine — each was discovered by one man.

Only the individual can think, and thereby create new values for society — nay, even set up new moral standards to which the life of the community conforms. Without creative, independently thinking and judging personalities the upward development of society is as unthinkable as the development of the individual personality without the nourishing soil of the community. The health of society thus depends quite as much on the independence of the individuals composing it as on their close political cohesion. It has been said very justly that Graeco-Europeo- American culture as a whole, and in particular its brilliant flowering in the Italian Renaissance, which put an end to the stagnation of medieval Europe, is based on the liberation and comparative isolation of the individual.

Let us now consider the times in which we live. How does society fare, how the individual? The population of the civilised countries is extremely dense as compared with former times; Europe today contains about three times as many people as it did a hundred years ago. But the number of great men has decreased out of all proportion. Only a few individuals are known to the masses as personalities, through their creative achievements. Organisation has to some extent taken the place of the great man, particularly in the technical sphere, but also to a very perceptible extent in the scientific.

The lack of outstanding figures is particularly striking in the domain of art. Painting and music have definitely degenerated and largely lost their popular appeal. In politics not only are leaders lacking, but the independence of spirit and the sense of justice of the citizen have to a great extent declined. The democratic, parliamentarian regime, which is based on such independence, has in many places been shaken, dictatorships have sprung up and are tolerated, because men's sense of the dignity and the rights of the individual is no longer strong enough. In two weeks the sheep-like masses can be worked up by the newspapers into such a state of excited fury that the men are prepared to put on uniform and kill and be killed, for the sake of the worthless aims of a few interested parties. Compulsory military service seems to me the most disgraceful symptom of that deficiency in personal dignity from which civilized mankind is suffering today. No wonder there is no lack

of prophets who prophesy the early eclipse of our civilization. I am not one of these pessimists; I believe that better times are coming... This text was written by Einstein in German and first published in 1934. The selections presented above are taken from pages 7 to 10 of the English translation by Alan Harris, published by The Philosophical Library, New York, in 1949, under the title The World as I see It.

A few dates

|

1879 |

Birth of Albert Einstein in Ulm, Germany. |

|

1900 |

Einstein becomes Swiss citizen. |

|

1905 |

Special Relativity. |

|

1914 |

Appointed in Prussian Academy of Sciences, Berlin. |

|

1915 |

General Theory of Relativity. |

|

1919 |

Confirmation of Einstein's theory by astronomers. |

|

1921 |

Nobel prize of physics. |

|

1933 |

Einstein leaves Germany and settles in America (Princeton). |

|

1955 |

Death of Einstein. |

The New Physics

In two articles published in 1905, Einstein initiated two revolutionary trends in scientific thought. One was his special theory of relativity; the other was a new way of looking at electromagnetic radiation which was to become characteristic of quantum theory, the theory of atomic phenomena.

Einstein strongly believed in nature's inherent harmony, and throughout his scientific life his deepest concern was to find a unified foundation of physics. He began to move toward this goal by constructing a common framework for electrodynamics and mechanics, the two separate theories of classical physics. This framework is known as the special theory of classical physics. It unified and completed the structure of classical physics, but at the same time it involved radical changes in the traditional concepts of space and time. Ten years later Einstein proposed his general theory of relativity, in. which the framework of the special theory is extended to include gravity. This is achieved by further drastic modifications of the concepts of space and time.

The other major development in twentieth-century physics was a consequence of the experimental investigation of atoms. At the turn of the century physicists discovered several phenomena connected with the structure of atoms, such as X-rays and radioactivity, which were inexplicable in terms of classical physics. Besides being objects of intense study, these phenomena were used, in most

ingenious ways, as new tools, to probe deeper into matter than had ever been possible before.

This exploration of the atomic and subatomic world brought scientists in contact with a strange and unexpected reality that shattered the foundations of their world view and forced them to think in entirely new ways. Nothing like that had ever happened before in science. Revolutions like those of Copernicus and Darwin had introduced profound changes in the general conception of the universe, changes that were shocking to many people, but the new concepts themselves were not difficult to grasp. In the twentieth century, however, physicists faced, for the first time, a serious challenge to their ability to understand the universe. Every time they asked nature a question in an atomic experiment, nature answered with a paradox, and the more they tried to clarify the situation, the sharper the paradoxes became. In their struggle to grasp this new reality, scientists became painfully aware that their basic concepts, their language, and their whole way of thinking were inadequate to describe atomic phenomena.

It took these physicists a long time to accept the fact that the paradoxes they encountered are an essential aspect of atomic physics, and to realise that they arise whenever one tries to describe atomic phenomena in terms of classical concepts. Once this was perceived, the physicists began to learn to ask the right questions and to avoid contradictions, and finally they found the precise and consistent mathematical formulation of that theory. Quantum theory, or quantum mechanics as it is also called, was formulated during the first three decades of the century by an international group of physicists including Max Planck, Albert Einstein, Niels Bohr, Louis De Broglie, Erwin Schrodinger, Wolfgang Pauli, Werner Heisenberg, and Paul Dirac.

Even after the mathematical formulation of quantum theory was completed, its conceptual framework was by no means easy to accept. Its effect on the physicists' view of reality was truly shattering. The new physics necessitated profound changes in concept of space, time, matter, object, and cause and effect; and because these concepts are so fundamental to our way of experiencing the world, their transformation came as a great shock. To quote Heisenberg, "The violent reaction to the recent development of modem physics can only be understood when one realises that here the foundations of physics have started moving; and that this motion has caused the feeling that the ground will be cut from science."

Einstein experienced the same shock when he was confronted with the new concepts of physics, and he described his feelings in terms very similar to Heisenberg's: "All my attempts to adapt the theoretical foundations of physics to this [new type of] knowledge failed completely. It was as if the ground had been pulled out from under one, with no firm foundation to be seen anywhere, upon which one could have built." To the end of his life Einstein could not reconcile himself to accept the consequences of the theory that his earlier work had helped to establish.

Out of the revolutionary changes in our concepts of reality that were brought about by modem physics, a consistent world view is now emerging. This view is not shared by the entire physics community, but is being discussed and elaborated by many leading physicists whose interest in their science goes beyond the technical aspect of their research. The scientists are deeply interested in the philosophical implications of modem physics and are trying m an open-minded way to improve their understanding of the nature of reality.

In contrast to the mechanistic Cartesian view of the world, the world view emerging from modem physics can be characterised by words like organic, holistic, and ecological. The universe is no longer seen as a machine, made up of a multitude of objects, but has to be pictured as one indivisible, dynamic whole whose parts are essentially interrelated and can be understood only as patterns of a cosmic process. An increasing number of scientists are aware that mystical thought provides a consistent and relevant philosophical background to the theories of contemporary science, a conception of the world in which the scientific discoveries of men and women can be in perfect harmony with their spiritual aims.

Extract from: Fritj of Capra, The Turning Point (London, flamingo edition, 1983), pp.63 ff.

Suggestions for further reading

Barnett, Lincoln. The Universe and Dr. Einstein. New York: Bantam Books, 1968.

Calder, Nigel. Einstein's Universe. Penguin Books, 1985.

Capra, Fritjof. The Tao of Physics. Berkeley, Shambhala Publications, 1975.

Einstein, Albert. Essays in Science. New York: Philosophical Library, 1934.

The Evolution of Physics. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1967.

Ideas and Opinions. New York: Bonanza, 1954.

The Meaning of Relativity. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 1967.

Out of my Later Years. Totowa: Littlefield, Adams, 1967.

The World as I See It. New York: Philosophical Library, 1949.

Schilpp, Paul Arthur. Albert Einstein: Philosopher - Scientist. New York: Tudor, 1951.

Talbot, Michael. Mysticism and the New Physics. New York: 1981.

Related Books

- Alexander the Great

- Arguments for The Existence of God

- But it is done

- Catherine The Great

- Danton

- Episodes from Raghuvamsham of Kalidasa

- Gods and The World

- Homer and The Iliad - Sri Aurobindo and Ilion

- Indian Institute of Teacher Education

- Joan of Arc

- Lenin

- Leonardo Da Vinci

- Lincoln Idealist and Pragmatist

- Marie Sklodowska Curie

- Mystery and Excellence on The Human Body

- Nachiketas

- Nala and Damayanti

- Napoleon

- Parvati's Tapasya

- Science and Spirituality

- Socrates

- Sri Krishna in Brindavan

- Sri Rama

- Svapnavasavadattam

- Taittiriya Upanishad

- The Aim of Life

- The Crucifixion

- The Good Teacher and The Good Pupil

- The Power of Love

- The Siege of Troy

- Uniting Men - Jean Monnet