The Aim of Life - Search For Utter Transcendence

Search For Utter Transcendence

Introduction

The Upanishad describes Reality as Sat, Being; but it also speaks of asat, Non- being, as the Ultimate from which Being appeared. This nothing, this Nihil, is seen as a "something" which is beyond positive comprehension. Just as pure Being is the affirmation of the Ultimate as the free base of all cosmic existence, so Non-being is the contrary affirmation of the Ultimate s freedom from all cosmic existence. Non- being permits Being as Silence permits activity. It is necessary to grapple with these concepts if we are to understand the message of the Buddha. It has been said that the Buddha rejected the teaching of the Upanishads and the Veda and maintained a Nihil or a zero as final and ultimate. But examining more closely what he is reported to have said about the ultimate reality, it becomes clear that he did not want any formula that would limit what he had experienced as something incapable of being described as either Being or Non-being.

The Buddha achieved Buddhahood and the state of Nirvana when he was only 35 years old. And having reached this state, he did not cease to be engaged in activity. The possibility of having an entirely motionless personality and a void calm within, while outwardly manifesting the eternal verities — Love, Truth and Righteousness — was perhaps the real gist of the Buddha s message. Indeed, it must be affirmed that he did not represent the petty ideal of an escape from the trouble and suffering of physical birth, but rather showed that a perfect man could combine

in himself both silence and activity, and that the absolute freedom of Nirvana could be reached without losing hold on existence and the universe.

The life of the Buddha, known also as Gautama and Sakyamuni, has fascinated people throughout history. That he was born around 560 BC in the Himalayan town of Kapilavastu, into the Sakya clan, and given the name Siddhartha, which means "wish fulfilled", is part of what is agreed to be factual of the beginning of the Buddha's life. Later tradition recounts the appearance and early life of the Buddha through history mixed with myth and legend.

It is said that before he was conceived, his mother, Mahamaya, dreamt of a beautiful white elephant entering her side. At his birth his body was found to bear thirty-two auspicious marks. Seven Brahmin priests predicted that if the child remained at home he would become a universal monarch; if, on the other hand, he encountered four signs — an old man, a sick man, a dead man and a wandering ascetic — he would renounce his worldly life, attain wisdom and enlighten the world. But the eighth priest to examine the new-born child, Kondanna, was unequivocal: the baby's markings could indicate only one thing, namely, the boy would one day renounce the world and become a Buddha, an enlightened being. Indeed, so impressed was Kondanna that he himself decided to renounce the world, and accompanied by four friends of like mind he went away to wait for Siddhartha to grow up and attain Buddhahood.

Suddhodana, Siddhartha's father, took every precaution that the four signs might not come within the sight of his son. The Buddha himself is reported to have said about his upbringing:

Bhikkus [disciples], I was delicately nurtured, exceedingly delicately nurtured, delicately nurtured beyond measure. In my father's residence lotus ponds were made, one of blue lotuses, one of red lotuses, and another of white lotuses, just for my sake. ...I had three palaces: one for winter, one for summer, and one for the rainy season.1

But in later youth, some years after his marriage to his cousin Yasodhara, he was confronted with the four signs and one night he slipped away from the palace. Taking up the life of a wandering ascetic he went in search of a teacher, and eventually associated with the greatest masters of his time. From these men he learned all they could teach, became their equal, even surpassed them, and yet remained unsatisfied. He then, with a group of companions — Kondanna and the

1. Angultara Nikaya, Collection of the Gradual Sayings of the Buddha.

four others who had been waiting for him all these years — began to practise severe austerities and self-mortification. It was a period of self-discovery in which he depended upon direct personal knowledge and direct personal experience. He is said to have described that at a certain stage, through a disciplined lack of food his body reached a state such that when he would touch the skin of his stomach he took hold of his spine.

After six years of such practices the Buddha remembered an experience of his childhood. Once, while waiting for his father under the shade of a jambu tree, he had spontaneously entered a state of consciousness characterised by a sense of freedom, bodily well-being and mental happiness. With this memory he realised that fasting and a life of extreme asceticism was not the way to achieve passionlessness, enlightenment and liberation. He stopped his austerities and soon regained his old health and robustness. But his companions were shocked and upset at his abrupt change. They decided to have no more to do with him and departed, leaving him behind.

In the neighbourhood at that time there lived a woman named Sujata. She was expecting a baby and had vowed that if it were a son she would make a special food- offering to the deity of a nearby banyan tree. The son was duly born and Sujata set about the elaborate ritual of preparing a meal fit for a god. When it was ready she put it in a golden bowl and sent her maid to the tree to make arrangements. Meanwhile, Gautama had sat down under this very tree to meditate. When the maid approached she thought the golden-hued figure was truly a god and rushed back to tell her mistress. Sujata came hurrying with her bowl and offered it to Gautama, saying, "Venerable Sir, whoever you may be, god or human, please accept this food and may you achieve the goal to which you aspire. " Taking the bowl, Gautama ate the meal. He then went to the river and placed the bowl upon the water. "If today I am to attain enlightenment, " he said, "may this golden bowl float upstream. " The bowl immediately did so.

That evening, Gautama made his way to the Bodhi tree, resolved not to rise until he reached enlightenment. Mara, an evil demon, appeared to him to try to keep him from his goal with threats, provocations, violence, and when these did not succeed, with enticement and alluring temptations. To Mara, the Buddha said:

Lust is your first army; the second is dislike for higher life; the third is hunger and thirst; the fourth is craving; the fifth is torpor and sloth; the sixth is fear, cowardice; the seventh is doubt; the eighth is hypocrisy and obduracy; the ninth is gains, praise, honour, false glory; the tenth is exalting self, despising others. Mara, these are your

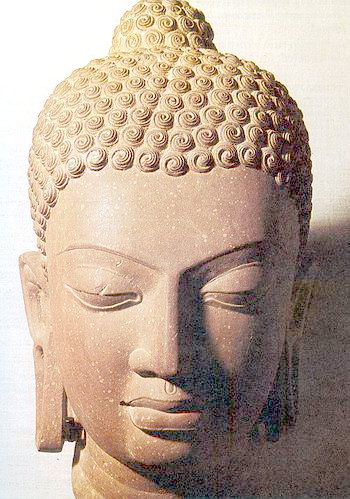

Mathura Museum, Gupta art, 5th centure

armies. No feeble man can conquer them, yet only by conquering them one wins bliss. I challenge you! Shame on my life if defeated! Better for me to die in battle than live. defeated....

Mara replied:

For seven years have I followed the Lord step by step. I can find no entrance to the All- enlightened, the watchful one. As a crow went after a stone that looked like a lump of fat, thinking, surely, here I shall find a tender morsel, and finding no sweetness there, departed thence; so like a crow attacking a rock, in disgust I leave Gautama,

Mara retreated and the Buddha achieved his goal.

The Buddha debated whether he should undertake the path of communicating to others the truth of the state he had reached. He compared the world to a lotus pond: in a lotus pond there are some lotuses still under water; there are others that have risen up only to water level; and there are still others that stand above water and are untouched by it. Similarly, in this world there are men of different levels of development — surely some would need and understand his teaching. Since his former teachers were no longer living, the Buddha sought out his original five companions, those who had left him in disgust, among whom was Kondanna. The Buddha began to teach, and, at the Deer Park, Isipatana, now called Sarnath, delivered his first message, known as the Dhammacakkappavattanasutta, "Setting in Motion the Wheel of Truth ".from which here is an extract:

Now this, O monks, is the noble truth of pain: birth is painful, old age is painful, sickness is painful, death is painful. Contact with unpleasant things is painful, separation from pleasant things is painful and not getting what one wishes is also painful. In short the five khandhas of grasping are painful.

Now this, O monks, is the noble truth of the cause of pain: that craving, which leads to rebirth, combined with pleasure and lust, finding pleasure here and there, namely the craving for passion, the craving for existence, the craving for non-existence.

Now this, O monks, is the noble truth of the cessation of pain: the cessation without a remainder of that craving, abandonment, forsaking, release, non-attachment.

Now this, O monks, is the noble truth of the way that leads to the cessation of pain: this

is the noble Eightfold Path, namely, right views, right intention, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, right concentration.1

Thereafter, according to tradition, the Buddha journeyed from place to place for more than 40 years, speaking to all who would listen.2 He acquired a unique reputation as a great teacher. Behind his philosophy and strict ethics he is described as having a quiet sense of humour and as being affectionate and devoted to his disciples. Although gifts of land and buildings were offered to him by his followers, he appears to have had no settled dwelling place. Near the age of eighty, the Buddha made his final journey to the sola tree grove at Kushinara. His last words to his disciples were these: "It is in the nature of all things that take form to dissolve again. Strive earnestly [to attain perfection]. " It is said that the Buddha then moved through various rapturous stages of meditation until he reached final and perfect Nirvana.

The awareness of suffering and death in this world is what sent the young Siddhartha on his quest. What, he asked, is the cause of suffering? He found it to be desire. In order to eliminate desire from our consciousness he proposed an eight-fold path through which one could be liberated into a state free from all affliction, a state of unshakable and perfectly unassailable peace. But, having reached this state, is there anything left to be done in this world? Is there any aim of life to be further pursued? As we have seen, the life of the Buddha shows clearly that the state of Nirvana and the state of activity need not be opposed to each other. For man, when liberated from desire, is motivated to act by something else. Action does not necessarily have its origin in desire. True action proceeds from Silence, and there are deeper and deeper profundities of silence, each corresponding to a greater effectivity of action. At the deepest, or highest, state of Silence, we find the Buddhahood. Thus was it possible for the Buddha to attain the state of Nirvana and yet act in the world, impersonal in his inner consciousness, in his action the most powerful personality we know of as having lived and produced results upon earth...

1.Dhammacakkappavattana-katha, Mahavagga, Part. I (Bom. Uni., 1944), pp. 15-16.

2. The oldest documents purporting to be the teaching of Buddha are the Pitakas or "Basket of the Law", prepared for the Buddhist Council of 241 BC, accepted by it as genuine, transmitted orally for four centuries from tlie death of Buddha, and finally put into writing, in the Pali tongue, about 80 BC. These Pitakas are divided into three groups: the Suttas, or tales, the Vmaya or discipline; and the Abhidhamma, or doctrine. Among these writings, the Dhammapada (in Pali: "Words of Doctrine", or "Way of Truth") is probably the best known book in the Pali Buddhist canon and the most quoted in other Buddhist writings: an anthology of basic Buddhist teachings (primarily ethical teachings) in an easy aphoristic style. As the second text in the Khuddaka Nikaya ("Short Collection") of the Sutta Pittaka, TheDhammapada contains 423 stanzas arranged in 26 chapters.

Ajanta

Dhammapada (a few extracts)

The Flowers

Who will conquer this world of illusion and the kingdom of Yama' and the world of the gods? Who will discover the path of the Law as the skilled gardener discovers the rarest of flowers?

The disciple on the right path will conquer this world of illusion and the kingdom of Yama and the world of the gods. He will discover the path of the Law as the skilled gardener discovers the rarest of flowers.

Knowing his body to be as impermanent as foam and as illusory as a mirage, the disciple on the right path will shatter the flowery arrow of Mara and will rise beyond the reach of the King of Death.

Death carries away the man who seeks only the flowers of sensual pleasure just as torrential floods carry away a sleeping village.

Death, the destroyer, overcomes the man who seeks only the flowers of sensual pleasure before he can satisfy himself.

The sage should go from door to door in his village, as the bee gathers honey from the flowers without bringing harm to their colours or their fragrance.

Do not criticise others for what they do or have not done, but be aware of what, yourself, you do or have not done.

Just as a beautiful flower which is radiant yet lacks fragrance, so are the beautiful words of one who does not act accordingly.

Just as a beautiful flower which is both radiant and sweetly scented, so are the beautiful words of one who acts accordingly.

Just as many garlands can be made from a heap of flowers, so a mortal can accumulate much merit by good deeds.

The fragrance of flowers, even that of sandalwood or of incense, even that of jasmine, cannot go against the wind; but the sweet fragrance of intelligence goes against the wind. All around the man of intelligence spreads the fragrance of his virtue.

No fragrance, not even that of sandalwood or incense, nor of the lotus nor of jasmine, can be compared with the fragrance of intelligence.

Weak is the fragrance of incense or sandalwood compared to that of a virtuous man which reaches up to the highest of divinities.

Mara cannot discover the way that those beings follow who lead a life of perfect purity and who are liberated by their total knowledge.

As the beautiful scented lily rises by the wayside, even so the disciple of the Perfectly Enlightened One,2 radiant with intelligence, rises from the blind and ignorant multitude.

The Fool

Long is the night for one who sleeps not; long is the road for one who is weary; long is the cycle of births for the fool who knows not the true law.

If a man cannot find a companion who is his superior or even his equal, he should resolutely follow a solitary path; for no good can come from companionship with a fool.

The fool torments himself by thinking, "This son is mine, this wealth is mine." How can he possess sons and riches, who does not possess himself?

The fool who recognises his foolishness is at least wise in that. But the fool who thinks he is intelligent, is a fool indeed.

Even if the fool serves an intelligent man throughout his life, he will nevertheless remain ignorant of the truth, just as the spoon knows not the taste of the soup

If an intelligent man serves a wise man, if only for a moment, he will quickly understand the truth, just as the tongue instantly perceives the savour of the soup.

The fools, those who are ignorant, have no worse enemies than themselves; bitter is the fruit they gather from their evil actions.

The evil action which one repents later brings only regrets and the fruit one reaps will be tears and lamentations.

The good action one does not need to repent later brings no regret and the fruit one reaps will be contentment and satisfaction.

As long as the evil action has not borne its fruits, the fool imagines that it is as sweet as honey. But when this action bears its fruits, he reaps only suffering.

Though month after month the fool takes his food with the tip of a blade of Kusa grass,3 he is not for all that worth a sixteenth part of one who has understood the truth.

An evil action does not yield its fruits immediately, just as milk does not at once turn sour; but like a fire covered with ashes, even so smoulders the evil action.

Whatever vain knowledge a fool may have been able to acquire, it leads him only to his ruin, for it breaks his head and destroys his worthier nature.

The foolish monk thirsts after reputation, and a high rank among the Bhikkhus, after authority in the monastery and veneration from ordinary men.

"Let ordinary men and holy ones esteem highly what I have done; let them obey me!" This is the longing of the fool, whose pride increases more and more.

One path leads to earthly gain and quite another leads to Nirvana. Knowing this, the Bhikkhu, the disciple of the Perfectly Enlightened One, longs no more for honour, but rather cultivates solitude.

The Sage

We should seek the company of the sage who shows us our faults, as if he were showing us a hidden treasure; it is best to cultivate relations with such a man because he cannot be harmful to us. He will bring us only good.

One who exhorts us to good and dissuades us from doing evil is appreciated, esteemed by the just man and hated by the unjust.

Do not seek the company or friendship of men of base character, but let us consort with men of worth and let us seek friendship with the best among men.

He who drinks directly from the source of the Teaching lives happy in serenity of mind. The sage delights always in the Teaching imparted by the noble disciples of the Buddha.

Those who build waterways lead the water where they want; those who make arrows straighten them; carpenters shape their wood; the sage controls himself.

No more than a mighty rock can be shaken by the wind, can the sage be moved by praise or blame.

The sage who has steeped himself in the Teaching, becomes perfectly peaceful like a deep lake, calm and clear.

Wherever he may be, the true sage renounces all pleasures. Neither sorrow nor happiness can move him.

Neither for his own sake, nor for the sake of others does the sage desire children, riches or domains. He does not aim for his own success by unjust ways. Such a man is virtuous, wise and just.

Few men cross to the other shore. Most men remain and do no more than run up and down along this shore.

But those who live according to the Teaching cross beyond the realm of Death, however difficult may be the passage.

The sage will leave behind the dark ways of existence, but he will follow the way of light. He will leave his home for the homeless life and in solitude will seek the joy which is so difficult to find.

Having renounced all desires and attachments of the senses, the sage will cleanse himself of all the taints of the mind.

One whose mind is well established in all the degrees of knowledge, who, detached from all things, delights in his renunciation, and who has mastered his appetites, he is resplendent, and even in this world he attains Nirvana.

The Adept

No sorrow exists for one who has completed his journey, who has let fall all cares, who is free in all his parts, who has cast off all bonds.

Those who are heedful strive always, and, like swans leaving their lakes, leave one home after another.

Those who amass nothing, who eat moderately, who have perceived the emptiness of all things and who have attained unconditioned liberation, their path is as difficult to trace as that of a bird in the air.

One for whom all desires have passed away and who has perceived the emptiness of all things, who cares little for food, who has attained unconditioned liberation, his path is as difficult to trace as that of a bird in the air.

Even the Gods esteem one whose senses are controlled as horses by the charioteer, one who is purged of all pride and freed from all corruption.

One who fulfils his duty is as immovable as the earth itself. He is as firm as a celestial pillar, pure as an unmuddied lake; and for him the cycle of births is completed.

Calm are the thoughts, the words and the acts of one who has liberated himself by the true knowledge and has achieved a perfect tranquillity.

The greatest among men is he who is not credulous but has the sense of the Uncreated, who has cut all ties, who has destroyed all occasion for rebirth.

Whether village or forest, plain or mountain, wherever the adepts may dwell, that place is always delightful.

Delightful are the forests which are shunned by the multitude. There, the adept, who is free from passion, will find happiness, for he seeks not after pleasure.

The Thousands

Better than a thousand words devoid of meaning is a single meaningful word which can bring tranquillity to one who hears it.

Better than a thousand verses devoid of meaning is a single meaningful verse which can bring tranquillity to one who hears it.

Better than the repetition of a hundred verses devoid of meaning is the repetition of a single verse of the Teaching which can bring tranquillity to one who hears it.

The greatest conqueror is not he who is victorious over thousands of men in battle, but he who is victorious over himself.

The victory that one wins over oneself is of more value than victory over all the peoples.

No god, no Gandharva,4 nor Mara nor Brahma can change that victory to defeat.

If, month after month, for a hundred years one offers sacrifices by the thousand, and if for a single instant one offers homage to a being full of wisdom, that single homage is worth more than all those countless sacrifices.

If for a hundred years a man tends the flame on Agni's altar, and if, for a single instant, he renders homage to a man who has mastered his nature, this brief homage has more value than all his long devotions.

Whatever the sacrifices and oblations a man in this world may offer

throughout a whole year in order to acquire merit, that is not worth even a quarter of the homage offered to a just man.

For one who is respectful to his elders, four things increase: long life, beauty, happiness and strength.

A single day spent in good conduct and meditation is worth more than a hundred years spent in immorality and dissipation.

A single day of wisdom and meditation is worth more than a hundred years spent in foolishness and dissipation.

A single day of Strength and energy is worth more than a hundred years spent in indolence and inertia.

A single day lived in the perception that all things appear and disappear is worth more than a hundred years spent not knowing that they appear and disappear.

A single day spent in contemplation of the path of immortality is worth more than a hundred years lived in ignorance of the path of immortality.

A single day spent in contemplation of the supreme Truth is worth more than a hundred years lived in ignorance of the supreme Truth.

The Ego

If a man holds himself dear, let him guard himself closely. The sage should watch through one of the three vigils of his existence (youth, maturity, or old age).

One should begin by establishing oneself in the right path; then, one will be able to advise others. Thus the sage is above all reproach.

If one puts into practice what he teaches to others, being master of

himself, he can very well guide others; for in truth it is difficult to master oneself.

In truth, one is one's own master, for what other master can there be? By mastering oneself, one acquires a mastery which is difficult to achieve.

The evil done by himself, originated by himself, emanating from him, crushes the fool as the diamond crushes a hard gem.

Just as the creeper clings to the Sal tree, even so one entrapped by his own evil actions does to himself the harm his enemy would wish him.

It is so easy to do oneself wrong and harm, but how difficult it is to do what is good and profitable!

The fool who, because of his wrong views, rejects the teachings of the adepts, the Noble Ones, and the Just, brings about his own destruction, as the fruit of the bamboo kills the plant.

Doing evil, one harms oneself; avoiding evil, one purifies oneself; purity and impurity depend on ourselves; no one can purify another.

No man should neglect his supreme Good to follow another, however great. Knowing clearly what is his best line of conduct, he should not swerve from it.

The Awakened One (The Buddha)

He whose victory has never been surpassed nor even equalled — which path can lead to Him, the Pathless, the Awakened One who dwells within the Infinite?

One in whom there is neither greed nor desire, how can he be led astray? Which path can lead to Him, the Pathless, the Awakened One who dwells within the Infinite?

Even the gods envy the sages given to meditation, the Awakened Ones, the Vigilant who live with delight in renunciation and solitude.

It is difficult to attain to human birth. It is difficult to live this mortal life. It is difficult to obtain the good fortune of hearing the True Doctrine. And difficult indeed is the advent of the Awakened Ones.

Abstain from evil; cultivate good and purify your mind. This is the teaching of the Awakened Ones.

Of all ascetic practices patience is the best; of all states the most perfect is Nirvana, say the Awakened Ones. He who harms others is not a monk. He who oppresses others is not a true ascetic.

Neither to offend, nor to do wrong to anyone, to practise discipline according to the Law, to be moderate in eating, to live in seclusion, and to merge oneself in the higher consciousness, this is the teaching of the Awakened Ones.

Even a rain of gold would not be able to quench the thirst of desire, for it is insatiable and the origin of sorrows. This the sage knows.

Even the pleasures of heaven are without savour for the sage. The disciple of the Buddha, of the Perfectly Awakened One, rejoices only in the extinction of all desire.

Impelled by fear, men seek refuge in many places, in the mountains, in the forests, in the groves, in sanctuaries.

But this is not a safe refuge; this is not the supreme refuge. Coming to this refuge does not save a man from all sufferings.

One who takes refuge in the Buddha, in the Dhamma5 and the Sangha," with perfect knowledge, perceives the Four Noble Truths:

Suffering, the origin of suffering,

the cessation of suffering

and the Noble Eightfold Path which leads

to cessation of suffering.

In truth,

this is the sure refuge,

this is the sovereign refuge.

To choose this refuge is to be liberated

from all suffering.

It is difficult

to meet the Perfectly Noble One.

Such a being is not born everywhere.

And where such a sage is born,

those around him live in happiness.

Happy is the birth of the Buddhas,

happy the teaching of the true Law.

Happy is the harmony of the Sangha,

happy the discipline of the United.

One cannot measure

the merit of the man who reveres

those who are worthy of reverence,

whether the Buddha or his disciples,

those who are free from all desire

and all error,

those who have overcome

all obstacles and who have crossed beyond

suffering and grief.

The Path

The best of all paths is the Eightfold Path; the best of all truths is the Fourfold Truth; the best of all states is freedom from attachment; the best among men is the One who sees, the Buddha.

Truly, this is the Path; there is no other which leads to purification of vision. Follow this Path and Mara will be confounded.

By following this Path, you put an end to suffering. This Path I have made known, since I learned to remove the thorns (of life).

The effort must come from oneself. The Tathagatas7 only point out the Path. Those who meditate and tread this Path are delivered from the bondage of Mara.

"All conditioned things are impermanent." When one has seen that by realisation, he is delivered from sorrow. That is the Path of purity. "All conditioned things are subject to suffering." When one has seen that by realisation, he is delivered from sorrow. That is the Path of purity.

"All things are insubstantial." When one has seen that by realisation, he is delivered from sorrow. That is the Path of purity.

He who though young and strong, does not act when it is time to act, is given to indolence, and his mind is full of vain thoughts; one who is so indolent will not find the Path of wisdom

Moderation in speech, control of the mind, abstention from evil actions, thus these three modes of action are to be purified first of all, to attain the Path shown by the sages.

From meditation wisdom springs, without meditation wisdom declines. Knowing the two paths of progress and decline, a man should choose the Path which will increase his wisdom.

Cut down all the forest (of desires) and not one tree alone; for from this forest springs fear. Cut down this forest of trees and undergrowth, 0 Bhikkhus. Be free from desire.

As long as one has not rooted out of oneself entirely the desire of a man for a woman, the mind is captive, as dependent as a suckling on its mother.

Root out self-love, as one plucks with his hand an autumn lotus. Cherish only the Path of the peace of Nirvana that the Sugata8 has taught us.

"Here shall I live in the rainy season; I shall stay there in the winter and elsewhere in the summer." Thus thinks the fool and knows not what may befall him.

And this man who is attached to his children and his cattle, is seized by death and carried off, as a sleeping village is swept away by torrential floods.

Neither children, nor father, nor family can save us. When death seizes us, our kinsmen cannot save us.

Knowing this perfectly, the intelligent man, guided by good conduct, does not delay in taking up the path which leads to Nirvana.

1. Yama: The God of Death.

2. The Perfectly Enlightened One'. The Buddha.

3. Taking one's food with the tip of a blade of Kusa grass symbolises an act of asceticism.

4. Gandharva: Celestial musician.

5. Dhamma: the True Doctrine.

6. Sangha: the community; the order of the Great Ones and the order of the monks.

7. Tathagatas: The Buddhas who, according to tradition, came on earth to reveal the eternal Truth.

8. Sugata: the Buddha.

Notes

During his lifetime, the Buddha's ideas spread rapidly through the north of India, where he had begun his teaching, and some Buddhists could be found in every part of the peninsula.

In the years that followed, Buddhist monasteries developed into notable centres of learning and stimulated the growth of the new religion. For a while it seemed that the whole subcontinent might become Buddhist. The future of Buddhism seemed especially bright under the Mauryan dynasty, which lasted from 322 to about 184 BC. The first king of this dynasty, Chandragupta Maurya (322- 298 BC), came closer to uniting India than had any earlier ruler; only the extreme south escaped his domination. The third Mauryan king, Asoka (ca. 273-ca. 232 BC), became a Buddhist, and with his support Buddhism developed into the first great missionary religion. In Asoka's days Buddhism was accepted in most parts of India and throughout Ceylon. Later it spread to the countries of Southeast Asia and across the mountains into China. And with Buddhism went Indian art, literature, and philosophy. The influence that India still exercises in eastern Asia began with this cultural expansion under Asoka.

Suggestions for further reading

Arnold, Sir Edwin. The Light of Asia (Many editions).

Coomaraswamy, Ananda K. Buddha and the Gospel of Buddhism. New York: Verry, 1964.

David-Neel, Alexandra. Buddhism : its Doctrines and its Methods. London: B.I. Publications, 1977.

Dhammapada, The. Trs. Thera Narada. London: John Murray, 1972.

Saddhatissa, H. Buddhist Ethics. London: Alien & Unwin, 1970.

The Buddha s Way. London: Alien & Unwin, 1971

The Life of the Buddha. New York: Harper & Row, 1976.

Thomas, E. J. Life of Buddha as Legend and History. London and New York: Routledge,1975. ¦ Way of the Buddha, The. Publication Division: Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Gov. of I India. (Published on the occasion of the 2500th anniversary of the Mahaparanirvana of Buddha). '

...the adoration group of the mother and child before the Buddha, one of the most profound, tender and noble of the Ajanta masterpieces....

The Adoration Group: mother and child befor Buddha, Ajanta (copy Nandala Bose)

Related Books

- Alexander the Great

- Arguments for The Existence of God

- But it is done

- Catherine The Great

- Danton

- Episodes from Raghuvamsham of Kalidasa

- Gods and The World

- Homer and The Iliad - Sri Aurobindo and Ilion

- Indian Institute of Teacher Education

- Joan of Arc

- Lenin

- Leonardo Da Vinci

- Lincoln Idealist and Pragmatist

- Marie Sklodowska Curie

- Mystery and Excellence on The Human Body

- Nachiketas

- Nala and Damayanti

- Napoleon

- Parvati's Tapasya

- Science and Spirituality

- Socrates

- Sri Krishna in Brindavan

- Sri Rama

- Svapnavasavadattam

- Taittiriya Upanishad

- The Aim of Life

- The Crucifixion

- The Good Teacher and The Good Pupil

- The Power of Love

- The Siege of Troy

- Uniting Men - Jean Monnet