Napoleon - The French Revolution

Portrait of General Bonaparte during the campaign of Italy, by Giuseppe Longhi

The French Revolution

by Sri Aurobindo

In this text, Sri Aurobindo, the great Indian sage and yogi, gives a deep commentary on the French Revolution and its prodigious inheritor, Napoleon.

The greatness of the French Revolution lies not in what it effected, but in what it thought and was. Its action was chiefly destructive. It prepared many things, it founded

nothing. Even the constructive activity of Napoleon only built a halfway house in which the ideas of 1789 might rest until the world was fit to understand them better and really fulfil them. The ideas themselves were not new; they existed in Christianity and before Christianity they existed in Buddhism; but in 1789 they came out for the first time from the Church and the Book and sought to remodel government and society. It was an unsuccessful attempt, but even the failure changed the face of Europe. And this effect was chiefly due to the force, the enthusiasm, the sincerity with which the idea was seized upon and the thoroughness with which it was sought to be applied. The cause of the failure was the defect of knowledge, the excess of imagination. The basal ideas, the types, the things to be established were known; but there had been no experience of the ideas in practice. European society, till then, had been permeated, not with liberty, but with bondage and repression; not with equality, but with inequality and injustice;

not with brotherhood, but with selfish force and violence. The world was not ready, nor is it even now ready for the fullness of the practice. It is the goal of humanity, and we are yet far off from the goal. But the time has come for an approximation being attempted. And the first necessity is the discipline of brotherhood, the organisation of brotherhood,— for without the spirit and habit of fraternity neither liberty nor equality can be maintained for more than a short season. The French were ignorant of this practical principle; they made liberty the basis, brotherhood the superstructure, founding the triangle upon its apex. For owing to the dominance of Greece and Rome in their imagination they were saturated with the idea of liberty and only formally admitted the Christian and Asiatic principle of brotherhood. They built according to their knowledge, but the triangle has to be reversed before it can stand permanently.

***

The action of the French Revolution was the vehement death-dance of Kali trampling blindly, furiously on the ruins She made, mad with pity for the world and therefore utterly pitiless. She called the Yatudhani in her to her aid and summoned up the Rakshasi. The Yatudhani is the delight of destruction, the fury of slaughter, Rudra in the Universal Being, Rudra, the bhuta, the criminal, the lord of the animal in man, the lord of the demoniac, Pashupati, Pramathanatha. The Rakshasi is the unbridled, licentious self-assertion of the ego which insists on the gratification of all its instincts good and bad and furiously shatters all opposition. It was the Yatudhani and the Rakshasi who sent their hoarse cry over France, adding to the luminous mantra, Liberty, Equality, Fraternity, the stern and terrible addition "or Death." Death to the Asura, death to all who oppose God's evolution, that was the meaning. With these two terrible Shaktis Kali did Her work. She veiled Her divine knowledge with the darkness of wrath and passion, She drank blood as wine, naked of tradition and convention She danced over all Europe and the whole continent was filled

with the war cry and the carnage and rang with the hunkara and the attahasyam. It was only when She found that She was trampling on Mahadeva, God expressed in the principle of Nationalism, that She remembered Herself, flung aside Napoleon, the mighty Rakshasa, and settled down quietly to her work of perfecting nationality as the outer shell within which brotherhood may be securely and largely organised.

***

The Revolution was also great in its men filling them all with its vehemence, its passion, its fierce demand on the world, its colossal impetus. Through four of them chiefly it helped itself, through Mirabeau, Danton, Robespierre and Napoleon. Mirabeau initiated, Danton inspired, Robespierre slew, Napoleon fulfilled. The first three appeared for the moment, the man in the multitude, did their work and departed. The pace was swift and, if they had remained, they would have outstayed their utility and injured the future. It is always well for the man to go the moment his work is done and not to outstay the Mother's welcome. They are fortunate who get that release or are wise enough, like Garibaldi, to take it. Not altogether happy is their lot who, like Napoleon or Mazzini, outstay the lease of their appointed greatness.

***

Mirabeau ruled the morning twilight, the sandhya of the new age. Aristocratic tribune of the people, unprincipled champion of principles, lordly democrat, — a man in whom reflection was turbulent, prudence itself bold, unflinching and reckless, the man was the meeting-place of two ages. He had the passions of the past, not its courtly restraint; the turbulence, genius, impetuosity of the future, not its steadying attachment to ideas. There is an honour of the aristocrat which has its root in manners and respects the sanctity of its own traditions; that is the honour of the Conservative. There is an honour of the democrat which has its

root in ideas and respects the sanctity of its own principles; that is the honour of the Liberal. Mirabeau had neither. He was the pure egoist, the eternal Rakshasa. Not for the sake of justice and liberty did he love justice and liberty but for the sake of Mirabeau. Had his career been fortunate, the forms of the old regime wide enough to satisfy his ambitions and passions, the upheaval of 1789 might have found him on the other side. But because the heart and senses of Mirabeau were unsatisfied, the French Revolution triumphed. So it is that God prepares the man and the moment, using good and evil with a divine impartiality for His mighty ends. Without the man the moment is a lost opportunity; without the moment the man is a force inoperative. The meeting of the two changes the destinies of nations and the poise of the world is altered by what seems to the superficial an accident.

There are times when a single personality gathers up the temperament of an epoch or a movement and by simply existing ensures its fulfilment. It would be difficult to lay down the precise services which made the existence of Danton necessary for the success of the Revolution. There are certain things he did, and no man else could have done, which compelled destiny; there are certain things he said which made France mad with resolution and courage. These words, these doings ring through the ages. So live, so immortal are they that they seem to defy cataclysm itself and insist on surviving eternal oblivion. They are full of the omnipotence and immortality of the human soul and its lordship over fate. One feels that they will recur again in aeons unborn and worlds untreated. The power from which they sprang, expressed itself rarely in deeds and only at supreme moments. The energy of Danton lay dormant, indolent, scattering itself in stupendous oratory, satisfied with feelings and phrases. But each time it stirred, it convulsed events and sent a shock of primal elemental force rushing through the consciousness of the French nation. While he lived, moved, spoke, felt, acted, the energy he did not himself

use, communicated itself to the millions; the thoughts he did not utter, seized on minds which took them for their own; the actions he might have done better himself, were done worse by others. Danton was contented. Magnificent and ostentatious, he was singularly void of personal ambition. He was satisfied to see the Revolution triumph by his strength, but in the deeds of others. His fall removed the strength of victorious Terror from the movement within France, its impulse to destroy and conquer. For a little while the impetus gathered carried it on, then it faltered and paused. Every great flood of action needs a human soul for its centre, an embodied point of the Universal Personality from which to surge out upon others. Danton was such a point, such a centre. His daily thoughts, feelings, impulses gave an equilibrium to that rushing fury, a fixity to that pregnant chaos. He was the character of the Revolution personified, — its heart, while Robespierre was only its hand. History which, being European, lays much stress on events, a little on speech, but has never realised the importance of souls, cannot appreciate men like Danton. Only the eye of the seer can pick them out from the mass and trace to their source those immense vibrations.

***

One may well speak of the genius of Mirabeau, the genius of Danton; it is superfluous to speak of the genius of Napoleon. But one cannot well speak of the genius of Robespierre. He was empty of genius; his intellect was acute and well-informed but uninspired; his personality fails to impress. What was it then that gave him his immense force and influence? It was the belief in the man, his faith. He believed in the Revolution, he believed in certain ideas, he believed in himself as their spokesman and executor; he came to believe in his mission to slay the enemies of the idea and make an end. And whatever he believed, he believed implicitly, unfalteringly, invincibly and pursued it with a rigid fidelity. Mirabeau, Danton, Napoleon were all capable of permanent discouragement, could recognise that they were beaten, the

hour unsuitable, fate hostile. Robespierre was not. He might recoil, he might hide his head in fear, but it was only to leap again, to save himself for the next opportunity. He had a tremendous force of sraddha. It is only such men, thoroughly conscientious and well-principled, who can slay without pity, without qualms, without resting, without turning. The Yatudhani seized on him for her purpose. The conscientious lawyer who refused a judgeship rather than sacrifice his principle by condemning a criminal to death, became the most colossal political executioner of his or any age. As we have said, if Danton was the character of the French Revolution personified when it went forth to slay, Robespierre was its hand. But, naturally, he could not recognise that limitation; he aspired to think, to construct, to rule, functions for which he was unfit. When Danton demanded that the Terror should cease and Mercy take its place, Robespierre ought to have heard in his demand the voice of the Revolution calling on him to stay his sanguinary course. But he was full of his own blind faith and would not hear. Danton died because he resisted the hand of Kali, but his mighty disembodied spirit triumphed and imposed his last thought on the country. The Terror ceased; Mercy took its place. Robespierre, however, has his place of honour in history; he was the man of conscience and principle among the four, the man who never turned from the path of what he understood to be virtue.

***

Napoleon took up into himself the functions of the others. As Mirabeau initiated destruction, he initiated construction and organisation and in the same self-contradictory spirit; he was the Rakshasa, the most gigantic egoist in history, the despot of liberty, the imperial protector of equality, the unprincipled organiser of great principles. Like Danton, he shaped events for a time by his thoughts and character. While Danton lived, politics moved to a licentious democracy, war to a heroism of patriotic defence. From the time he passed, the spirit of Napoleon shaped events and politics moved to the rule first of the civil, then of the military dictator,

war to the organisation of republican conquest. Like Robespierre he was the executive hand of destruction and unlike Robespierre the executive hand of construction. The fury of Kali became in him self-centred, capable, full of organised thought and activity, but nonetheless impetuous, colossal, violent, devastating.

II

Napoleon

The name of Napoleon has been a battle-field for the prepossessions of all sorts of critics, and, according to their predilections, idiosyncrasies and political opinions, men have loved or hated, panegyrised or decried the Corsican. To blame Napoleon is like criticising Mont Blanc or throwing mud at Kanchenjunga. This phenomenon has to be understood and known, not blamed or praised. Admire we must, but as minds, not as moralists. It has not been sufficiently perceived by his panegyrists and critics that Bonaparte was not a man at all, he was a force. Only the nature of the force has to be considered. There are some men who are self-evidently superhuman, great spirits who are only using the human body. Europe calls them supermen, we call them vibhutis. They are manifestations of Nature, of divine power presided over by a spirit commissioned for the purpose, and that spirit is an emanation from the Almighty, who accepts human strength and weakness but is not bound by them. They are above morality and ordinarily without a conscience, acting according to their own nature. For they are not men developing upwards from the animal to the divine and struggling against their lower natures, but beings already fulfilled and satisfied with themselves. Even the holiest of them have a contempt for the ordinary law and custom and break them easily and withOut remorse, as Christ did on more than one occasion, drinking wine, breaking the Sabbath, consorting with publicans and harlots; as Buddha did when he abandoned his self-accepted duties as a husband, a citizen and a father; as Shankara did when he broke the holy law and trampled upon custom and achar

to satisfy his dead mother. In our literature they are described as Gods or Siddhas or Titans or Giants. Valmiki depicts Ravana as a ten-headed giant, but it is easy to see that this was only the vision of him in the world of imaginations, the "astral plane", and that in terms of humanity he was a vibhuti or superman and one of the same order of beings as Napoleon.

* * *

The Rakshasa is the supreme and thoroughgoing individualist, who believes life to be meant for his own untrammelled self-fulfilment and self-assertion. A necessary element in humanity, he is particularly useful in revolutions. As a pure type in man he is ordinarily a thing of the past; he comes now mixed with other elements. But Napoleon was a Rakshasa of the pure type, colossal in his force and attainment. He came into the world with a tremendous appetite for power and possession and, like Ravana, he tried to swallow the whole earth in order to glut his supernatural hunger. Whatever came in his way he took as his own, ideas, men, women, fame, honours, armies, kingdoms; and he was not scrupulous as to his right of possession. His nature was his right; its need his justification. The attitude maybe expressed in some such words as these, "Others may not have the right to do these things, but I am Napoleon."

* * *

The Rakshasa is not an altruist. If by satisfying himself he can satisfy others, he is pleased, but he does not make that his motive. If he has to trample on others to satisfy himself, he does so without compunction. Is he not the strong man, the efficient ruler, the mighty one? The Rakshasa has Kama, he has no Prema. Napoleon knew not what love was; he had only the kindliness that goes with possession. He loved Josephine because she satisfied his nature, France because he possessed her, his mother because she was his and congenial, his soldiers because they were

necessary to his glory. But the love did not go beyond his need of them. It was self-satisfaction and had no element init of self-surrender. The Rakshasa slays all that opposes him and he is callous about the extent of the slaughter. But he is never cruel. Napoleon had no taint of Nero in him, but he flung away without a qualm whole armies as holocausts on the altar of his glory; he shot Hofer and murdered Enghien. What then is in the Rakshasa that makes him necessary? He is individuality, he is force, he is capacity; he is the second power of God, wrath, strength, grandeur, rushing impetuosity, overbearing courage, the avalanche, the thunderbolt; he is Balaram, he is Jehovah, he is Rudra. As such we may admire and study him.

* * *

But the Vibhuti, though he takes self-gratification and enjoyment on his way, never comes for self-gratification and enjoyment. He comes for work, to help man on his way, the world in its evolution. Napoleon was one of the mightiest of Vibhuties, one of the most dominant. There are some of them who hold themselves back, suppress the force in their personality in order to put it wholly into their work. Of such were Shakespeare, Washington, Victor Emmanuel. There are others like Alexander, Caesar, Napoleon, Goethe, who are as obviously superhuman in their personality as in the work they accomplish. Napoleon was the greatest in practical capacity of all moderns. In capacity, though not in character, he resembles Bhishma of the Mahabharat. He had the same sovran, irresistible, world-possessing grasp of war, politics, government, legislation, society; the same masterly handling of masses and amazing glut for details. He had the iron brain that nothing fatigues, the faultless memory that loses nothing, the clear insight that puts everything in its place with spontaneous accuracy. It was as if a man were to carry Caucasus on his shoulders and with that burden race successfully an express engine, yet note and forecast every step and never falter. To prove that anything in a human body could be capable of such work, is by itself a service

to our progress for which we cannot be sufficiently grateful to Napoleon.

* * *

The work of Bonaparte was wholly admirable. It is true that he took freedom for a season from France, but France was not then fit for democratic freedom. She had to learn discipline for awhile under the rule of the soldier of Revolution. He could not have done the work he did, hampered by an effervescent Parliament ebullient in victory, discouraged in defeat. He had to organise the French Revolution so far as earth could then bear it, and he had to do it in the short span of an ordinary lifetime. He had also to save it. The aggression of France upon Europe was necessary for selfdefence, for Europe did not mean to tolerate the Revolution. She had to be taught that the Revolution meant not anarchy, but a reorganisation so much mightier than the old that a single country so reorganised could conquer united Europe. That task Napoleon did effectively. It has been said that his foreign policy failed, because he left France smaller than he found it. That is true. But it was not Napoleon's mission to aggrandise France geographically. He did not come for France, but for humanity, and even in his failure he served God and prepared the future. The balance of Europe had to be disturbed in order to prepare new combinations and his gigantic operations disturbed it fatally. He roused the spirit of Nationalism in Italy, in Germany, in Poland, while he established the tendency towards the formation of great Empires; and it is the harmonized fulfilment of Nationalism and Empire that is the future. He compelled Europe to accept the necessity of reorganisation political and social.

The punya of overthrowing Napoleon was divided between England, Germany and Russia. He had to be overthrown, because, though he prepared the future and destroyed the past, he misused

the present. To save the present from his violent hands was the work of his enemies, and this merit gave to these three countries a great immediate development and the possession of the nineteenth century. England and Germany went farthest because they acted most wholeheartedly and as nations, not as Governments. In Russia it was the Government that acted, but with the help of the people. On the other hand, the countries sympathetic to Napoleon, Italy, Ireland, Poland, or those which acted weakly or falsely, such as Spain and Austria, have declined, suffered, struggled and, even when partially successful, could not attain their fulfilment. But the punya is now exhausted. The future with which the victorious nations made a temporary compromise, the future which Napoleon saved and protected, demands possession, and those who can reorganise themselves most swiftly and perfectly under its pressure, will inherit the twentieth century; those who deny it, will perish. The first offer is made to the nations in present possession; it is withheld for a time from the others. That is the reason why Socialism is most insistent now in England, Germany and Russia; but in all these countries it is faced by an obstinate and unprincipled opposition. The early decades of the twentieth century will select the chosen nations of the future.

* * *

There remains the question of Nationalism and Empire; it is put to all these nations, but chiefly to England. It is put to her in Ireland, in Egypt, in India. She has the best opportunity of harmonising the conflicting claims of Nationalism and Empire. In fighting against Nationalism she is fighting against her own chance of a future, and her temporary victory over Indian Nationalism is the one thing her guardian spirits have most to fear. For the recoil will be as tremendous as the recoil that overthrew Napoleon. The delusion that the despotic possession of India is indispensable to her retention of Empire, may be her undoing. It is indispensable to her, if she meditates, like Napoleon, the conquest of Asia and of the world; it is not necessary to her imperial self-fulfilment,

for even without India she would possess an Empire greater than the Roman. Her true position in India is that of a trustee and temporary guardian; her only wise and righteous policy the devolution of her trust upon her ward with a view to alliance, not ownership. The opportunity of which Napoleon dreamed, a great Indian Empire, has been conceded to her and not to Napoleon. But that opportunity is a two-edged weapon which, if misused, is likely to turn upon and slay the wielder.

Taken from Sri Aurobindo, The French Revolution,

in "The Hour of God", SABCE (1972) edition, Vol. 17, pp. 577-87

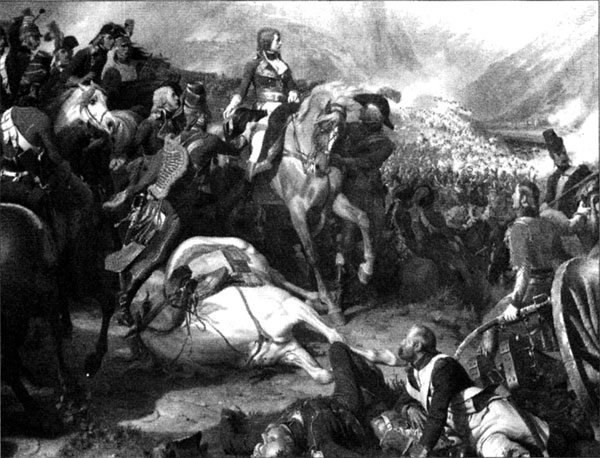

Two contrasted episodes in Napoleon's life. Above, the Battle of Rivoli in 1797 where Bonaparte defeated the Austrians, which led to French occupation of northern Italy. Below, a scene of the retreat from Russia, in 1812.

Related Books

- Alexander the Great

- Arguments for The Existence of God

- But it is done

- Catherine The Great

- Danton

- Episodes from Raghuvamsham of Kalidasa

- Gods and The World

- Homer and The Iliad - Sri Aurobindo and Ilion

- Indian Institute of Teacher Education

- Joan of Arc

- Lenin

- Leonardo Da Vinci

- Lincoln Idealist and Pragmatist

- Marie Sklodowska Curie

- Mystery and Excellence on The Human Body

- Nachiketas

- Nala and Damayanti

- Napoleon

- Parvati's Tapasya

- Science and Spirituality

- Socrates

- Sri Krishna in Brindavan

- Sri Rama

- Svapnavasavadattam

- Taittiriya Upanishad

- The Aim of Life

- The Crucifixion

- The Good Teacher and The Good Pupil

- The Power of Love

- The Siege of Troy

- Uniting Men - Jean Monnet