Napoleon - Dresden the Zenith

Book V - Dresden: the Zenith

The excessive weight of this man in human destiny disturbed the equilibrium. This individual counted of himself alone, more than the universe besides. These plethoras of all human vitality concentrated in a single head, the world mounting to the brain of one man, would be fatal to civilisation if they should endure.

— Victor Hugo.

We now touch upon the most extraordinary period in Napoleon's momentous career, perhaps the most extraordinary throughout the whole course of human story, namely, the pageant of Dresden, when Napoleon's "star" had in truth reached its very zenith - when, during the latter half of May, 1812, surrounded by nearly every potentate of Europe, he posed as virtual Emperor of Europe - the highest pinnacle of human power which authentic history has to offer us. This passage in Bonaparte's epopee reads more like a bit of the wildest extravagance of exaggerated romance than a historical truism, the nearest approach to this state of human pre-eminence being Alexander after Arbela and Caesar after his victory at Munda - master of the Roman world, these two being the only great figures in history that in any way can be compared with Napoleon, Cyrus being too remote a prodigy for comparison. Many names besides Napoleon's are symbolical of great power and supremacy over mankind - Alexander, Caesar, Alaric, Attila, Theodoric, Charlemagne, Tamerlane, Charles V, are these. These great men - these Titans of history, all wielded abnormal power, but great as was their power and potential as was their influence over the destiny of the human race, Napoleon's was even greater and hisinfluence over the world still more potential.

Human genius in its highest state of exultation, the highest point which man has ever attained through the intellect, is to be found in Napoleon at Dresden. There in the blaze of the assembled sovereigns of Christendom, from the dizzy summit of his power, he beheld the world suppliant at his feet. At Dresden, Napoleon was in truth the king of kings, for every crowned head, from the Carpathians to the Rhine, had congregated there to pay him homage as his vassals. The Emperor of Austria, the Kings of Prussia, Saxony, Naples, Wurtemberg, and Westphalia, and a host of lesser satellites, were gathered there to obey the behest of the man who erstwhile had been but a mere subaltern in the French army and who now was the arbiter of the civilised world. That mortal ever rose to such an amazing height of power seems inconceivable, and had Bonaparte never existed, such a state of human pre-eminence would never have been deemed possible, if even conceived. An altitude of power as bewildering as that which Napoleon attained has scarcely been devised by the most fantastic imagination. Even the wildest vagaries of Oriental fable or Western fairy lore have not endued their heroes with more power than Napoleon wielded. The genii of the Arabian Nights never conceded an iota of the supremacy to which he had reached. We fully agree with Whately in his affirmation that Napoleon's career is a miracle. We even go further than Whately and say that Napoleon is a miracle - the miracle of the modern age, if miracles there be. A study of his career seems almost to reconcile us, in spite of ourselves, to the miraculous.

Among all the giants of history, in one respect especially, Napoleon is unique. Most of the world's Titans were either the sons of kings or scions of royal houses, or lineally affined to illustrious families. Alexander was the son of Philip, King of Macedonia; Theodoric, of Theodomir, King of the Ostrogoths; Charlemagne of the powerful Peppin, King of the Franks; Charles V was the grandson of the Emperor Maximilian, and Ferdinand the Catholic, king of Spain. Hannibal was the son of Hamilcar Barca, next to himself the greatest of Carthage's soldiers. Caesar

was of patrician birth. Both Alaric and Attila were potent rulers before entering upon their careers of conquest. Moreover, with the exception of Hannibal, who died by suicide, in exile, and Charles V, who abdicated voluntarily when at the height of his renown, they all died in the meridian of their power and glory. But with Napoleon it was otherwise. His father, Charles Bonaparte, although of good birth and even of noble descent, was only an impecunious lawyer of Corsica, unknown outside his native isle, and but for his illustrious son, the name of Bonaparte would not be to this day the shibboleth of a dynasty. Therefore, Napoleon's greatness seems all the greater by the comparative obscurity of his origin, which, when compared with that of the great predecessors, raises him, at least in our estimation, immeasurably above them all. He had to begin at the very root of things. If anyone truly earned his spurs it was he. Everything from his first commission to his throne and bewildering altitude of power he owed solely to himself - to his matchless genius. [...]

Napoleon, at Dresden, during the latter half of May, 1812, is significative of the most exalted state which man has perhaps ever attained. There, in the very heart of Europe, with empires as a footstool-with a supplicating humanity inert at his feet, he was the manifestation of human might in its most stupendous and strenuous form. Despite the magnificence by which he was environed - despite the apparent inviolableness of his position at Dresden, there is something ominous in the very exuberance of his power, for, strange inconsistency of Fate, was not the pageant of Dresden predictive of his impending portentous fall? Who that saw him then with kings as his retainers would have foretold that five months later his knell of doom would be sounded at Moscow? It is well-nigh impossible to appreciate the full import of Napoleon's power at this period of his career; however, a glance in retrospection may, perhaps, give us an idea of the prodigious power to which he had reached.

In the year 1795, seventeenyears before the pageant of Dresden, there was living in Paris, in the greatest obscurity and straitened circumstances, a young man whose prospects seemed about as

lugubrious as they could well be. By birth he was a Corsican, by calling an artillery officer, and despite his youth - he was only twenty-five years of age - had already distinguished himself in active service as a commandant of artillery. Having incurred the displeasure of the military authorities he had been obliged to resign his command and had come to Paris to solicit employment. An interview which he had with Aubry, the President of the Military Committee, had only conduced to render his position all the more desperate. Aubry, piqued at the young soldier's peremptory refusal to abandon the artillery and accept the command of a brigade of infantry in the Vandean War, caused his name to be struck off the register of general officers in employment.

Could any one's future offer a more hopeless prospect? His career, his hopes of future distinction (for his was an ardent, ambitious, even imaginative nature) seemed blighted for ever. That he had well-nigh succumbed to the stress of illfortune and thrown up the sponge in despair is clear enough, for, in his anguish of mind, he was on the verge of committing suicide and was only saved by the timely intervention of a friend. His ambition and day-dreams also seem to have degenerated with the continuous growth of his adversities - to have sunk to the prosaic level of those of a "petit bourgeois" for, with the resignation of a philosopher, he declared that life might be fairly tolerable if he could only afford to have a small house in the street where he lived, and to keep a cabriolet. The marriage of his elder brother with the daughter of a rich banker of Marseilles elicited from him a cry of reproof against the vagaries of fortune. Half in bitterness, half in pitying scorn would he often say, "How fortunate is that fool Joseph!" Yet, in spite of the overwhelming weight of his misfortunes, he was not utterly resigned to his bitter lot. His inordinate ambition made him recalcitrate against the obduracy of his cruel fate and the banalities of his existence. Even the baleful clouds that darkened his life were lit up by the radiance of his vivid imagination. In this dismal hour of his life his thoughts turned longingly towards the East. If in France he was unable to obtain distinction, then he would hither to the East, and win his laurels

there - the East which, to use his aphorism of later years, "only awaits a man". With the sanguineness of the dreamer he addressed a petition to the French Government, proposing that he, with a few artillery officers, be sent to Turkey to organise the Turkish artillery. For weeks the young commandant lived in the ferment of the wildest enthusiasm. The portals of renown seemed already open to him. We can picture him with his slim figure, pale, intelligent face and keen grey eyes, animated by the fire of enthusiasm, in his threadbare uniform, dreaming over his future renown and glory. We can almost hear him as he says in a transport of exultation, "How strange it would be if a little Corsican soldier became King of Jerusalem!" This dream, which to him seemed replete with a glorious promise, was never to be, his petition to the French Government remaining unanswered. His bumper of woe seemed, in truth, filled to overflowing - the Fates as relentless as ever. Little did he guess what the future held in store for him, little did he dream of the splendour that awaited him beyond the sullen horizon of his life's purview! There, reserved for him, was a destiny incomparably more glorious than that of a Godfroi de Bouillon, than a Saladin or even of a Tamerlane. It was not the East, however, he was to dominate, but the West, there to found an empire that would eclipse that of Charles the Great.

Seventeen years have rolled by - seventeen years of incessant warfare. A supreme genius now bursts upon the world. Conqueror of Italy and the East, he now controls the destiny of France. In his person is revived the Roman magisterial dignity of Consul, and as First Consul of the French Republic France is supreme in the West. Before long we see France discarding republicanism and assuming the Imperial Eagle and the insignia of autocracy. Her great dictator, invested with the Imperial dignity, is now Emperor of France, King of Italy, Lord of the West, and dictates to an empire whose confines stretch from the head-waters of the Tiber to the Zuider-Zee - an empire almost as extensive as that of Charlemagne. The floodgates of war now sunder open. From France's frontiers bursts with unbridled fury the angry tide of war. Before its mad onslaught empires and kingdoms are overthrown

— thrones fall; dynasties are extirpated. From the debris of nations new kingdoms are created. The tricolour waves exultantly over every capital in Europe - over Vienna, Berlin, Warsaw, Lisbon, Madrid, Rome, Florence, Naples, Munich, Milan, Venice, and Dresden. This tremendous upheaval in the political and social order of things is the work of a single individual. The Emperor of the West becomes Suzerain Lord of Europe, the subverter of dynasties, the creator of kings, the custodian of the Pope - the king of kings. At Austerlitz he dictates to an emperor; at Tilsit he remodels Europe, and his word is law to a continent, a king is his vassal, and the powerful autocrat of the East his sycophant; at Erfurt he is king of kings and at Dresden, the culminating point of his career, he is virtual Emperor of Europe. It is scarce conceivable that the man at Dresden in 1812, domineering over Europe and the obscure, impecunious young general of artillery, who seventeen years anteriorly, with blighted hopes, was a vagrant in Paris, were the same person - that the man of Dresden and the solitary denizen of the Rue Chanterine were both Napoleon - Napoleon at the zenith of his career and during the dismal hours of his youth. Has there ever been, throughout the whole course of history, such a transformation as this in the career of any other human being?

If one considers the bewildering height of Napoleon's power at Dresden, and even before then, the rapidity of his rise to the topmost pinnacle of supremacy is truly astounding. From the day his "star" first shone forth in its nascent brilliancy over the heights of Montenotte to the day of Dresden, when at its very zenith it scintillated in all its lucent splendour, was an interval of but sixteen years, and yet within this brief space of time were concentrated the vicissitudes, the changes of centuries. Within this lapse of time the face of Europe, of the civilised world, was utterly metamorphosed. The pageant of Dresden was the reward of Herculean toil unremitted during sixteen years - the goal attained, the outcome of twenty-two triumphs and the overthrow of a continent. [...] With regard to Napoleon it was very different. What was the political state of Europe at the close of the eighteenth century, when

Our Last Great Man

Bonaparte was winning his first laurels in Italy and the East? At that time there were four great Powers in Europe besides France - England, Austria, Prussia, and Russia. England, with her vast colonial empire ministering to her wealth, with her invincible navy sweeping the seas, was the emporium of the world. She was France's most redoubtable enemy. She had wrested Canada from her, driven the French from India, and but recently from Malta, and practically annihilated the French navy. [...] Austria was supreme in Central Europe. In the Netherlands and on the Rhine she had but recently been victorious over France. While Bonaparte, in Italy, was astounding the world by his innovations in the science of war, the Archduke Charles was victorious over

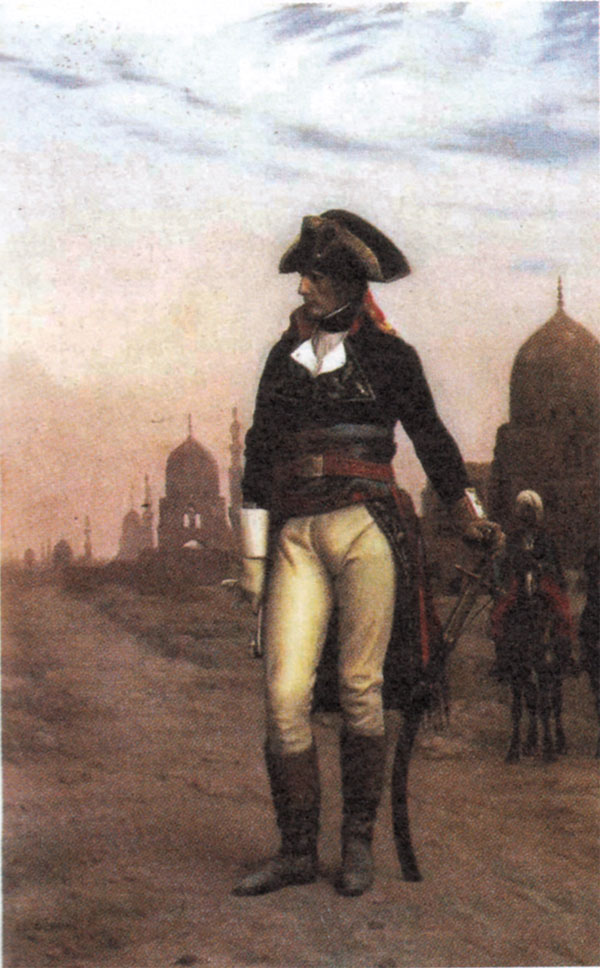

Napoleon in Egypt by painter Gerome

Jourdan at Wetzlar and Wurzburg and in the valley of the Po; he contended with Bonaparte for the supremacy in Italy. Prussia had but recently been greatly enlarged by her share of dismembered Poland. She was basking in the glory of Frederick's victories. Less than fifty years ago had she not humbled France at Rosbach? She was still under the spell of the glamour of that great day. She felt secure in her splendid army; and with just cause, for the Prussian army was reckoned perhaps the most perfectly disciplined army in the world. Russia, the colossal empire of Eastern Europe, was, next to France, perhaps the leading Power on the Continent of Europe. Her armies under Suwarrow, the greatest military genius of the time next to Napoleon, had triumphed over the Turks and the Poles. While Bonaparte was subjugating the Orient he extruded the French from Italy. The military skill of France's most able generals was of no avail against his superior genius. Russia it was that really overthrew Napoleon; the charred walls of Moscow, the snow-clad plains of Lithuania were more efficient towards the liberation of Europe than the united armies of Christendom.

Such was the political state of Europe at the close of the eighteenth century and at the dawn of the nineteenth, and these were the Powers Napoleon had to grapple with for the mastery of the world. Of the four great nations whose overthrow was essential for the gratification of his ambition England alone escaped the lion's claws. During nineteen years of incessant warfare she remained unscathed, invulnerable under the aegis of her invincible navy. In 1797 Austria was at Napoleon's mercy; in 1800 he ejected her from Italy; in 1805 she lay prostrate at his feet. In 1806 he annihilated Prussia and defeated Russia. In 1809, for the second time, he overthrew Austria. The supremacy of Dresden, the suzerainty of Europe was the recompense of these stupendous achievements. The vast power which Napoleon enjoyed at Dresden is the greatest reward of human endeavour the world has to offer us, only acquired by exploits as astounding as those he achieved. No human power, short of universal dominion, could be greater than that which Napoleon exercised from 1810 to 1812, culminating in the pageant of Dresden. Had he overthrown Russia in 1812 and

conquered England without doubt the world would have been at his feet. It was at Dresden, at the hour of his greatest prosperity, that Fortune, his faithful handmaiden for sixteen years, forsook him. She could no longer meet his demands. To no other mortal had she ever conceded so much. The pageant of Dresden is the uttermost limit of human transcendence on record throughout the history of the human race.

Taken from: Napoleon Our Last Great Man

By Elystan M. Beardsley, 1907

Sisley's Ltd. Makers of Beautiful Books,

London

Related Books

- Alexander the Great

- Arguments for The Existence of God

- But it is done

- Catherine The Great

- Danton

- Episodes from Raghuvamsham of Kalidasa

- Gods and The World

- Homer and The Iliad - Sri Aurobindo and Ilion

- Indian Institute of Teacher Education

- Joan of Arc

- Lenin

- Leonardo Da Vinci

- Lincoln Idealist and Pragmatist

- Marie Sklodowska Curie

- Mystery and Excellence on The Human Body

- Nachiketas

- Nala and Damayanti

- Napoleon

- Parvati's Tapasya

- Science and Spirituality

- Socrates

- Sri Krishna in Brindavan

- Sri Rama

- Svapnavasavadattam

- Taittiriya Upanishad

- The Aim of Life

- The Crucifixion

- The Good Teacher and The Good Pupil

- The Power of Love

- The Siege of Troy

- Uniting Men - Jean Monnet