Mystery and Excellence on The Human Body - Ayurvedic Nutrition

Ayurvedic nutrition

In the ancient medical system of India, we find what is one of the oldest and most time-tested approaches to nutrition. Its science of food and diet is an integral part of a philosophy of man, his consciousness and his relation to the universe. The result is an approach to diet that is unsurpassed both in its profundity and sophistication as well as in its practicality and simplicity. Here the selection and preparation of food is seen as inseparable from the treatment of disease and the cultivation of vibrant health. Both these goals are part of traditional Indian medicine.

The traditional system of Indian medicine is called Ayurveda. Ayur means "life" and veda means "science," so Ayurveda means "the Science of Life." It comprises a body of medical tradition that extends back at least several thousands of years. Moreover, it has continued to be practiced without interruption during this period of time, its present form having been shaped primarily by the writers Charaka, Shushruta and Vag Bhata prior to 500 B.C. It is thought that this codification rep resents a transfer of oral tradition into written, and it is considered likely by historians that the spoken tradition dates back much further. The form and organization given to the Ayurvedic system of medicine by Charaka and Shushruta has persisted, and these textbooks are still taught and used by medical students in the schools of traditional medicine throughout India today.

Through its long history, it would appear that Ayurveda witnessed the rise and fall of many schools of therapy ranging from herbal medicine to physical therapy and massage, surgery, psychiatry, the use of meditation, mantra and many other treatment modalities. Each of these apparently was integrated into the physician's practice, and the conceptual scheme expanded to accommodate them. As a result, the school of Ayurveda has a breadth and depth that could be unparalleled in the history of medical science. This also made it possible for Ayurvedic physicians, or vaidyas, to develop, over thousands of years, an extremely

complex and complete science of haematology and pharmacology. Long before we discovered their use in the West, traditional Indian physicians were using such preparations as reserpine to lower blood pressure and calm nerves, cardiac glycosides similar to digitalis to regulate the rhythm of the heart, and fungal preparations similar to penicillin as antibiotics. Their practice of surgery was astonishingly advanced for the time, and as early as 1,200 years ago, there are accounts of successful plastic surgery such as the replacement of ears and noses that had been severed in battle. Moreover, even in ancient times, the treatment of mental illness was advanced, and the treatment of physical disorders often involved definite mental, psychotherapeutic and meditative techniques. In fact, perhaps the one thing that can be said most clearly about Ayurveda is that it admits no distinction between mind and body, and that it provides one of the most comprehensive schemata for understanding psychosomatic interaction.

The science of nutrition in Ayurveda is vast and comprehensive and is not separated from pharmacology. Since no distinction is admitted between foods and drugs, herbal and mineral substances that are used in the preparation of food are thought to be equally important medicinally as those that are given separately.

Tridosha

Those few people who are familiar with the name of Ayurveda know that it is often taken to be synonymous with the concept of tridosha. Tridosha is that conceptual framework which forms the heart of Ayurvedic medicine, and a proper understanding of its meaning has been greatly hindered by this fact since most Western students tend to assume that the meanings of the terms used in tridosha are equivalent to the "humors" of Greek and medieval European medical thought. Though the "bile," "wind" and "phlegm" of the Europeans are apparently descendants of the ancient Indian concepts, they were (and are) too often corrupted by overly literal interpretation.

Tridosha is essentially a system of conceptualizing mind, body and their interaction in dynamic terms that cut across the usual categories of Western thought. Tridosha means the system of "three doshas." The doshas are dynamic factors of vectors whose interaction produces that complex known as the psychosomatic entity, or person. The doshas are called Vata, Pitta and Kapha. In Sanskrit, Kapha signifies all that about

the psychosomatic complex which is heavy, dense, gross, sluggish, coarse and tending toward the material. Pitta indicates that aspect of the total system which is hot, energetic, assertive, capable of doing work and having the property of fire. Vata, the last aspect of the psycho-physiological system, represents that which is least tangible, least perceptible, most subtle, most active, erratic and unpredictable. For this reason, it is often translated "wind". It is the wind which we cannot see, which moves in such subtle and erratic ways, yet which has the power to generate electricity, move ships or destroy cities.

Pitta is most often translated as fire, since in the natural world it is the flame which most closely corresponds to this aspect of the psycho somatic system. The flame is hot, quick, angry, aggressive, yet full of warmth, energy and the ability to act in the world. The normal "home" of this fire in the Ayurvedic system is the "solar plexus" whose name reflects the ancient recognition that the organs of digestion were the primary site where fuel is broken down and the whole process of energy production begins and is to a great extent regulated. Modem physiologists acknowledge that a significant amount of energy may be produced during the digestion and assimilation of foods.

Kapha is difficult to translate. It designates that aspect of the system which is most material. Sometimes it is connected with the earth or water since these are the material, tangible, grosser aspects of the universe. In the context of medicine, Kapha is often translated as "mucus," and as we noted earlier, there seems to be some etymological relation ship between the English cough and the Sanskrit Kaph, both of which are connected with the accumulation of mucus in the respiratory system. In a similar way, Pitta is often translated (though perhaps regrettably so) as "bile" since it is bile which is the identifiable fluid most closely connected to the digestive processes of the body. Vata's translation as "wind" is taken in the context of physiology to mean gas in the intestinal tract or elsewhere in the body. This is, of course, a limited aspect of its meaning, and the literal translation of the doshas as mucus or phlegm, bile and wind is clearly a misinterpretation of their intended significance.

Tridosha can perhaps be most aptly understood in the context of Western science if its derivation is likened to a process of factor analysis: if we can imagine the ancient physicians working primarily on the basis of empirical evidence gathered through self-scrutiny, careful

clinical experience and keen observation, if we can imagine their trying to analyze the multiplicity of psychological, emotional, mental, spiritual and physical phenomena into manageable terms, then we might see that their efforts amounted to something quite similar to what a computer does to a pile of data when it carries out a factor analysis. The reduction of the multiple variables into functionally-grouped categories not only brings order out of the chaos, but brings an order which, is most meaningful and revealing of the basic nature of the system being studied. This "factor analysis" carried out by the traditional physicians of India apparently revealed three major functional "forces" or groupings involved in the psychosomatic system, and these were designated as the doshas (that is, three main categories as far as understanding and dealing with disease).

It is through examining and evaluating in each patient the predominant activity, quality and imbalances in these three functional entities that the physician arrives at a conceptualization of the disease process. For instance, in some diseases Pitta might be greatly accentuated while Kapha is normal and Vata is deficient. Diagnosis is more complex than this, of course, since any one, any two, or all three of the doshas may be either accentuated, vitiated (i.e. irregularly or unevenly active), or decreased. The various combinations are many.

Of course, the use of the conceptual scheme is not limited to dealing with "disease". It is not necessary that one be disabled, nor that he apply to a physician for help to avail himself of the insights that tri dosha can provide. In fact, the Ayurvedic writings not only clarify diseases and functional disorders through use of tridosha, they also conceptualize the "normal" person in these terms. Though the ideal situation is one where the three doshas are in perfect harmony, such an ideal state rarely exists. Each person's makeup or constitution determines that he will tend to slip out of balance in certain characteristic ways, e.g., one may tend toward anger, volatileness and have a reputation as being "hot-headed". The red face, quick assertive manner and aggressive actions all suggest the "pittic" constitution. If there is, in addition, an erratic nature, an inconsistency and spaciness, then there is also an element of Vata involved. The person who is heavy, staid, unshakable, with perhaps a tendency toward lethargy and indifference, would be called kaphic.

Tridosha and taste

Ayurvedic science is, as we have seen, experiential and practical. It is first and foremost a way of organizing one's experience. Therefore, it is not surprising that its methods for judging the properties of foods and naturally occurring medicines (herbs, spices, mineral substances, etc.) is simple and part of one's everyday experience. In fact, as mentioned before, the properties of food and medicines as conceptualized in Ayurveda can be deduced by their tastes in most cases. There we find the sense of taste put in a different perspective: it has evolved to help us apprehend the dynamic qualities of foods so that we can judge their effect on us. Whether it is the vaidya in his pharmacy or the cook in his kitchen, one of the most important guides to the properties of food or drug is its taste.

Taste reflects certain qualities in the food — its ability to modify certain principles (doshas) — therefore one can know from the taste of the substance how it will affect the dynamic equilibrium of the body mind complex. ... The Ayurvedic pharmacology of taste is essentially a way of putting into formal terms the intuitive and experiential sense of what is right and proper to eat at any moment.

A person who is overweight, for example, and who is dull and heavy and lethargic, will find that he feels livelier, more active, and has less tendency to gain weight if his foods are predominantly pungent and bitter. His tendency, however, is likely to be the opposite of that since it is often this which has led him to over indulge in sweet foods in the first place. By contrast, a person who is very nervous, shaky, "spaced out," flighty and unable to "keep his feet on the ground," should not take a preponderance of bitter substances. If he does, he will tend to become even "spacier," and may even lose contact with reality. Such a person, the typical ectomorphic, intellectual, dreamy, paranoid recluse can usually benefit from some starchy, fattening food. This is the secret, perhaps, of much of the success of the macrobiotic diet which emphasizes whole grains, especially rice. Among the wandering youth of the mid and late 1960's, the "macrobiotic" diet gained quite a reputation. A steady diet of predominantly brown rice is often very settling, bringing the "spaced out" veteran of "mind-expanding" drugs down-to-earth and helping him feel more in touch with the world around him. Centres offering assistance based on such dietary practices have sometimes been dramatically helpful. Foods which are hot and spicy stimulate digestive fire,

and it is thus that traditional cooks the world over add chilis and pungent spices to their bean recipes so that the difficult-to-digest legume can be handled better and will not cause so much gas. The kashaya or astringent substances are a special case. Astringency is almost more of a sensation than a taste, strictly speaking. It is a drawing or pulling together, and according to Ayurvedic thought, this means that a cool, dry contraction is produced. Such a dynamic effect is useful where there is a preponderance of watery Kapha.Any discharge or flow from the body will be reduced by this, thus the universal use of astringent compounds in such cases from the American Indians' blackberry root or oak bark tea for diarrhoea to the current use of alum compounds in underarm anti-perspirants.

The appreciation of the taste-related properties allows one to be less crude in his understanding of the effects of foods. For example, before ripening, the banana has a subtle but distinct astringency. When properly cooked, it is therefore useful in such disorders as diarrhoea and runny, drippy colds. When the banana ripens, however, it loses its astringent taste and becomes quite sweet. At that point the drying and "drawing closed" effect is lost and increasingly replaced by its opposite, so that banana (which to most people means ripe banana) is notoriously "mucus forming."

There are other gunas or properties that food contains besides simply that of taste or rasa. Another is, for example, virya, which means the effect that the food has on the temperature of the body — does it create heat or does it make one cold? For instance, sesame seeds tend to generate heat in the body while mung beans tend to do the opposite. This is despite the fact, it should be noted, that both contain roughly similar quantities of protein, carbohydrate and fat. Here we are dealing with a subtler system of analysis than the laboratory method of simply determining the quantities of known nutrients. There is something about the non-nutritional compounds or properties of the sesame seed that has a specifically warming effect on the body and something about the mung bean that is the opposite.

Meats were classified in that way too by the ancients, and whereas most kinds of fish will tend to produce warmth, other meats do not seem to. Of course most spices, with the exception of cloves, are heat producing, while fruits are generally cooling though here, too, there are exceptions. In both the tropical plains of India and the icy Himalayan

slopes, heating or air-conditioning are still used very little. The traditional wisdom about virya is therefore adhered to carefully. A heating (ushna) food taken in the hot season can produce considerable discomfort. Sesame confections, for example, cannot be found in Indian sweet shops during the warm months, whereas in the winter they are especially favoured by those who suffer from the cold.

Altogether, there are twenty-two pairs of gunas, like heat-producing (ushna) versus cold-producing (shita). The more important of these are lightness versus heaviness and oiliness versus dryness. Among beans, for example, mung beans are considered light(laghu) and easy to digest, whereas kidney beans are heavy (guru). Both, however have the quality of dryness (rooksh). Urad dahl, on the other hand, another kind of legume, is considered oily or unctuous (snigdha), the opposite of dry.

Whether a food is drying (rooksh) or oily (unctuous or snigdha) is of some practical importance. Those who have problems with dry, hard bowel movements may find they have been eating foods that were pre dominantly rooksh. An increase of foods that are snigdha such as fats, ripe bananas, coconut, sugar and salt, can correct this. Similarly, one who is having a runny nose and eyes can often greatly relieve his discomfort by temporarily limiting his diet to more drying foods, herbs and seasonings like chick peas, honey or black pepper. The bajra chappati, made from the flour of a dark millet, is remarkable in its ability to dry up a drippy nose — especially in cool, damp weather.

Many of these properties are in line with common sense and do not come as a surprise because they are consonant with our experience. Most of the others follow logically from the principles of taste pharmacology. However, there is another set of properties which are not so apparent or logical. This is the "taste" (rasa) of the. food after it has undergone some process of digestion. This is called vipaka. For instance, most starchy foods after chewing, become sweet, and the post-digestion "taste" is sweet (madhura).But starchy foods tend to be classified as sweet (madhura) anyway, so the taste (rasa) is the same as the vipaka. Sometimes, however, this is not true, so that a predominantly starchy substance like mung beans, becomes pungent or kata after digestion. Thus the value of mung beans, for while they may be agree able in taste to those who prefer mild, sweetish foods, they will not be unduly fattening and actually help to stimulate the digestive fire.

The pharmacologic use of spices and foods

An understanding of the doshas and their relationship to the taste and other properties of food are part and parcel of common knowledge and folk culture in India. Everyone educated in the traditional way under stands, at least to some extent, these basic concepts. Classically, the selection of foods from the table and the choice of things to cook are based on seasonal and other considerations with an understanding of how they affect the doshas and what sorts of foods would be appropriate.

An appreciation of tridosha and the science of taste pharmacology also explains much of the use of spices in Indian cooking. When the seasonings and spices are added to a food, they change its taste. Therefore they change its properties and the effect that it has on the body. For instance, rice with salt and pepper will have quite a different effect on the physiology than rice alone. Though in Western scientific terms it is said that the spice has little nutritional value, in Ayurvedic terms it has a very specific pharmacologic action, such that he whole processing of the food and the net effect on the body is changed.

It is perhaps for this reason that the average Indian can eat a pre dominantly starchy diet made up of rice, chapatti, potatoes and dahl with a madhura rasa (sweet taste) as long as he adds his spices —

cumin, coriander, pepper, ginger, and so forth, which are predominantly katu or pungent with some bitter and astringent taste. They serve to balance the food and prevent it from having a fattening or kaphic effect. Of course, it is common sense, even to the Westerner, that seasoning a food so that it becomes hot and pungent decreases its mucus forming properties and "cleans out the sinuses."

During ancient times when the Ayurvedic scriptures were written, it seems that a more varied diet of fruit, vegetables, grains and wild and leafy greens was much more easily available. The population was less dense and there was more vegetation per person. At that time, it seems likely that the need for spices was less, and they seemed to have been used predominantly as medicine. But as the diet became increasingly domesticated and agricultural, and the population density greater, food became less varied and more starchy with a predominantly sweet taste (madhura rasa). It was then that the spices moved from the pharmacy into the kitchen, and their use became a daily necessity. Unfortunately, a very starchy diet sometimes leads to the heavy-handed use of the least expensive and most potent spices such as chili peppers. The result can be caustic, irritating and inflaming to the intestinal tract. In fact, the use of chilis, brought only a few hundred years ago from Mexico, might be regarded as a corruption of classical Indian cuisine. Many people have had tearful and burning experiences with so-called Indian food as a result of eating in East Indian restaurants. Actually, restaurants are not used by most people in India, and the preparation of food is carefully done at home. A mastery of subtle seasoning is the mark of a cultured and well-educated cook, and the judicious use of spices is considered a crucial part of turning out a meal that is not only nutritious but that can promote a gentle rebalancing of the system.

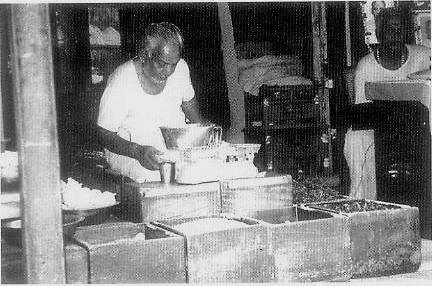

Because so little distinction is made between the pharmacy and the kitchen in traditional Indian culture, we find in Ayurvedic medical schools that pharmacology and cooking are taught as the same course. The culinary spices like cardamom, cumin, coriander, turmeric, etc. have always been an important part of the armaraentarium of tradition al physicians. Cardamom, for example, is an important cough remedy, and even today can be found in Western over-the-counter cough syrups. Moreover, many of the items which we regard as strictly foodstuffs are considered by the traditional physician to have important pharmacologic action. For instance, onions, honey, clarified butter, sesame seed oil,

milk, many meats, etc., are ascribed very specific and important medicinal effects.

Milk is a laxative, as is honey. Ghee (clarified butter) promotes digestion as do most fats, which is in accord with research which has shown that full-fat soy flour is digested with less gas than the defatted preparation. One can easily compile a list of over a hundred plants which are used in India both as food and as medication. This is another reason why both foods and medicinal substances are subsumed under the term dravya, and why in the discussions of taste and of the proper ties of foods and medicines, so little distinction is made between the two. The same methods of preparation, processing, handling, and selection are applicable to the major part of this spectrum of substances. It is for such reasons, too, that cooking and the preparation of medicine can be taught at the same time. In fact, the Ayurvedic physician who would attempt to prescribe medication without seeing to the preparation of the meals taken during the course of the day by a patient would be considered a fool.

Even among the Ayurvedic physicians, the matter is regarded as extremely complex, and even the most extensively tested rules, evolved over thousands of years, like that of the taste pharmacology, are not always completely accurate. The properties of perhaps 80% of foods and medicinal-like herbs can be deduced according to their taste (rasa). Another 10% or 15% must be explained by what happens after digestion occurs (vipakha) and a few others by the virya or other gunas. For example, honey, which is sweet in taste, is converted upon digestion to a pungent (katu) substance. This means that after it is processed by the body, it is transformed so that it does not have the effect that most sweet substances do. It does not aggravate the tendency toward obesity, nor does it increase the formation of mucus. Thus, instead of being a kaphic food, it is one which stimulates pitta and has exactly the opposite effect of most sweet foods. Because it is transformed by the body into a pungent or "hot" substance, it helps one lose weight, stimulates body heat and tends to dry up mucus. For this reason, it is sometimes used along with milk or yogurt to reduce their mucus-forming tendencies. The Ayurvedic scriptures say that yogurt is an excellent food if it is taken with honey. On this basis it is also said that the diabetic can take honey without harm, whereas he should avoid sugar assiduously. Conventional modem medicine, by contrast, has tended to forbid honey

to the diabetic on the rationale that it is a carbohydrate. Interestingly enough, however, honey contains primarily fructose which, as we have seen, is different from most sugars in that it does not require insulin for its metabolism. If taken in excess, however, honey can over stimulate and unbalance or disturb pitta, causing digestive problems that may be difficult to correct. For this reason, though it is an excellent food, one is counselled to take honey in proper measure (for most people more than two tablespoons a day is unwise).

All in all, there may be one food, herb, or spice in a thousand which falls into a special category which is called prabhava, meaning "it can't be explained!" This means that neither the taste, the virya, nor the vipaka can account for the effect that the food has on the body. In fact, these classifications are for convenience, simply a way of organizing the information that has been accumulated. Though they usually can be reasoned out and followed through, the designations were, and still are, derived empirically. That is, different foods were tried and their results (gunas) were catalogued, and thus they were designated a certain rasa, a certain virya or a certain vipaka. It is for this reason that the rasa (taste) sometimes cannot accurately predict the vipaka or the gunas (properties). Moreover, foods and plants not described in the ancient writings must be tested out today, as well as new varieties of the ancient plants or even those grown under vastly different conditions or on markedly different soils.

Ayurveda and the patterns of nature

The properties of the substance may be evident from the source of the food itself. For instance, the goat has the quality of being "dried up" and small. It also has a quickness, a lightness and a jumpiness that goes along with this. The ability of goat's milk to reduce diarrhoea and tighten the bowel movements is not surprising if one looks at the goat itself, whose feces are small and hard. The milk or meat of the water buffalo, however, stands in contrast. The water buffalo is an animal which is heavy, large, calm, quiet and slow to anger or-movement. Its feces are copious, loose and mushy. Its products are considered to be very good for people who are underweight, undernourished and nervous. It tends to calm them. In a similar way, the meat of certain birds is said, according to the traditional teachings, to be very good for heavy people. This is not as true, on the other hand, of those birds which are water dwellers.

The world of nature and the predominance of wild fruits, vegetables, herbs and game provided the Ayurvedic physicians with a rich store of foods having a wide variety of very specific effects. By pre scribing food alone, along with a few herbal seasonings, they were able to have a great impact on a person's health and often reversed serious chronic diseases. Moreover their theoretical framework, their conceptual scheme, based on tridosha and a holistic approach to observing the world of nature around them, permitted them to benefit from the complexity of natural substances.

This is why in Ayurvedic nutrition, one can deal with milk in dimensions that are quite impossible from the point of view of Western nutrition. Though goat's milk can be said, through the laboratory analysis of Western nutritionalists, to contain a bit less butterfat and perhaps more protein than cow's milk, according to Ayurveda, its unique properties can be deduced from its taste, which is somewhat astringent (kashaya). Thus its tendency is to draw together, pull tight and cure diarrhoea. This would lead one to think that it would be very effective in reducing weight which it has been found from experience to do, while the milk of the water buffalo has the opposite effect which the difference in its taste as well as the nature of the two animals would lead one to expect.

Ayurvedic nutrition is based on the concept that for each food, whether it is meat, fish, vegetable, fruit or milk, there is an essence or energy state or quality that can be identified and formulated. It can be partially identified through its taste and partially through the other properties which it is observed to manifest. Partly it can be identified by the observation of the personality or role of the plant or animal as it participates in the overall ecological system. Finally the essence of the food's effects can be formulated by using tridosha, a conceptual system that allows the physician enough breadth and depth to express such a holistic understanding. It is tridosha which has given the Ayurvedic physician the capacity to express his understanding of food in a way that is usable and practical since it can relate the uniqueness of the food to the present state of the person who is to eat it. Modem nutritional science in the West stands in dramatic contrast to this, of course. Here we have succeeded in attaining greater accuracy, dependability and predictability by studying much more limited and isolated components of food. By separating out the carbohydrates, the proteins, or certain

vitamins or minerals, we can make accurate predictions about how each will effect the body. Unfortunately, this is often difficult to relate to natural foods since each vegetable contains many nutrients and one may vary dramatically from the next in terms of its exact content of vitamins or minerals, and may include besides many other complex substances and properties which our analysis has overlooked. Thus, we might say that our Western analytic science of nutrition has attained greater precision at the expense of a sort of impoverishment: an appreciation of the richness and individuality of natural phenomena, both in the world of foods and in the world of human physiology, is lost.

Moreover, as we have seen before, a study of vitamins, minerals, and the other isolated components of food leaves us ill-equipped to deal with the practical situation of selecting this apple rather than that or one seasoning instead of a second. The practical, everyday, experiential situation of eating or preparing food seems far divorced from Western laboratory research on nutrition. By contrast, the Oriental science of nutrition is organized around and based on personal experience. It is through the inner experience of taste and one's reaction to the food that he formulates its properties. It is one's individuality and experience of himself that allows a conceptualization of how his system is functioning, i.e., a "diagnosis" in terms of tridosha. The focus of Ayur vedic nutrition is on the interaction between the person and the food and the directly observed and experienced reactions that occur.

Though Ayurveda is a medical science, its application is not limited to the physician. An understanding of the rudiments of Ayurveda is an important part of traditional education, and the physician's role is merely to be an expert or consultant in this area. The patient's role is to learn from the physician what he can about his own inner state, how it has become imbalanced, and how he can correct and prevent this through the proper selection of foods, herbs and condiments. The Ayurvedic physician is a teacher, and the patient takes over from him as treatment is terminated, the role of studying his own system, taking the management and maintenance of balance into his own hands.

From Rudolph Ballentine, M.D,

Diet And Nutrition: A Holistic Approach,

Himalayan International Institute, Honesdale, PA 18431, USA

Related Books

- Alexander the Great

- Arguments for The Existence of God

- But it is done

- Catherine The Great

- Danton

- Episodes from Raghuvamsham of Kalidasa

- Gods and The World

- Homer and The Iliad - Sri Aurobindo and Ilion

- Indian Institute of Teacher Education

- Joan of Arc

- Lenin

- Leonardo Da Vinci

- Lincoln Idealist and Pragmatist

- Marie Sklodowska Curie

- Mystery and Excellence on The Human Body

- Nachiketas

- Nala and Damayanti

- Napoleon

- Parvati's Tapasya

- Science and Spirituality

- Socrates

- Sri Krishna in Brindavan

- Sri Rama

- Svapnavasavadattam

- Taittiriya Upanishad

- The Aim of Life

- The Crucifixion

- The Good Teacher and The Good Pupil

- The Power of Love

- The Siege of Troy

- Uniting Men - Jean Monnet