Leonardo Da Vinci - Chapter III

"He filled entire pages with profiles..."

Chapter III

these artists who had everything to discover, and, who in less than a century did discover everything (the principle of perspective, the science of anatomy, the rules of light...) — one understands how this era is different from the others, and what makes it unique. It is a heroic age of which each masterwork is a trophy, the mark of a conquest. This huge conquest comes from a return to Nature, meaning to the real. Leonardo fulfilled this idea linking it to another one doubly significant: the desire not to repeat what was done before. He wrote: "How the art of painting slowly declines and is slowly lost from age to age when painters only have their predecessors as models."

But beginning with his sketches we see a demonstration of convergence of divergent concerns served by such a variety of means, that we find it difficult to reconcile such opposites in a single man. Often on the same page of his diagrams there is a constant going from one subject to another, attested by the juxtaposition of diagrams and notes that do not seem to have anything in common. For example, he filled entire pages with profiles and did so all his life. He drew a great number of them, all more or less the same: a repulsive, almost ferocious-looking old man, next to a handsome youth. In the domain of art, these diagrams represent grace and imagination on the one hand, and the

strict discipline of the scientific naturalist on the other. He was as much interested in gross deformities as in beauty. Technically speaking, the range of Leonardo was extraordinarily wide: he excelled as much in imprecise sketches — calm, with an infinite rigour of detail — as in the spontaneous study: quick, febrile and violent. These two methods are as far apart as possible from one and the other. The quality of qualities, in Leonardo's drawings, is this feeling of the free transfer of a vision to paper that has been neither clouded nor altered... And yet, there is so little apparent effort in this marvellous alchemy that everything happens as if, by the simple action of a demiurge, earth transmuted into heaven.

One of the first signed works of Leonardo is the landscape of Santa Maria della Neve, dated 2 August 1473, a drawing which was later considered as "the first real landscape sketch in the occidental art". In this work, what interested Leonardo more than description of the shapes of trees and rocks, was to capture the essence of the phenomena — winds, snow or rain moving through the sunlight. He expressed a new sensitivity to the values of light, which he vibrated with shadings, giving time density and transparency to the landscape. Volume and space, shadows and mist are animated by a powerful and dynamic stroke.

During his whole life, Leonardo had been obsessed by the movements of water. In his last years he started the series of strange, terrifying sketches, all under the name of Deluge. He predicted this Deluge would exterminate man and all his works, bringing an end to the world. Almost abstract and of a great audacity since he was breaking away from conventional art forms, these exercises of the imagination, of stupefying depth and vigour, show his passion for complex movements, for convolutions, as much as his dismay at the future of humanity. His scientific knowledge is used here, with an implacable logic, to demonstrate how poor the means at man's disposal when he struggles with Nature; one sees here a prodigious spirit dredging the secret depths of his anguished soul: "Ah! What frightening tumults resound in the sadness of the air," wrote Leonardo in the commentary which

described his sketches. "Ah! What lamentations!"

The enormity of his drawing work shows us that his life was a long preparation for the art of painting, which to him was the supreme art. But knowing that it was his duty to bring it to perfection, moreover aware, to the highest degree, of the complexity of Nature which he proposed to equal, he forced himself to a preliminary labour of a gigantic scope, seemingly out of proportion, with the number of works that he actually accomplished. That an artist could dedicate years to the mental incubation of a painting which sometimes he would even not complete, is what his public could not fathom. This is why after the flashing debut that had left an unforgettable impression, Leonardo little by little tired his patrons and the public and became a legendary figure, admired for his past prowess. But all the while he had been devoting himself to the meticulous elaboration of future works that were constantly postponed.

What was his method of working?

Before deciding to sculpt or to paint, he travelled the road from the minutest detail to entire organized form. Before working on the human body, he completely mastered its secret springs and the internal structure. "Having learned the nature of nerves, muscles and tendons", he wrote, "the painter will know exactly which nerves determine the movement of each member and their number, and which muscle provokes the contraction of the nerve when it swells, and what nerves, once converted into delicate cartilages envelop and contain this muscle. And so will he be able, in different ways and universally, to indicate the varied muscles, from the different poses of the figures." Leonardo's great contribution to anatomy lay in the creation of a system of drawing, still in general use, which enabled physicians to transmit their findings to students. Prior to his time the medical profession took little interest in anatomical drawing; many physicians actually opposed its use in books. Leonardo's

system involved the presentation of four views of a subject, and this was so clear and effective that physicians could no longer deny the value of art in teaching.

This rigourousness, which seemed to grow with age, explains both the severity of the study of drapes and the exuberance of the grotesque heads; he extended it to everything he perceived of the reality of the world. He was aware, above his senses, of the infinite plays of shadow and light, of the geometric sequences of the refraction.

The quality of grace comes before strength; the hyper-contracted muscles of Michaelangelo's figures would always displease Leonardo. The smiles that radiate throughout his most famous paintings prove that gracefulness is not only "more beautiful than beauty", but that it is stronger than strength.

Since light is God's first creation; it is the painter's first resource and should be his first care. The chiaroscuri, the sfumato make light spring from darkness, in a painting, as God made it spring in the world; a painting must express the splendour of light, which is the main characteristic of the Creation. In The Last Supper Leonardo tends to blend Christ with the light and Judas with the shadow; in The Virgin of the Rocks the Virgin is more brilliant than St Ann, on whose knees she is resting; the lower part of the body of the Mona Lisa is hardly seen on the background, on the contrary, her face is set on a luminous landscape. To Leonardo light was something toward which one climbs.

The artist in him wanted to embrace the whole of Nature, as if to build in his own vision, the unity of the spirit. Science and technique are always only auxiliaries to the service of art: "The one who disdains painting does not like Nature's philosophy. Painting is the most beautiful language of the mind."

The place that philosophy occupies in the life of the mind, the profound exigency of which it is the witness, the generalized curiosity that comes with painting or philosophy, the need for the number of facts that it holds and assimilates, the ever present thirst for cause, here was the permanent concern of the work of painting which occupied Leonardo.

In fact, Leonardo found in painting all the problems which the intention of a synthesis of Nature offered to the mind, because his painting always demanded of him a thorough and previous analysis of the objects he wished to represent, analysis which did not refer only to their visual characteristics, but which went to the most intimate or organic, to the physical, to the physiological, up to the psychological, so that in the end his eye, somehow, was able to perceive the visible characteristics of the model which resulted from its hidden structure.

In Leonardo's Treatise on Painting he speaks a lot about relief, on its nature, its function, on the different ways to translate it, that is, to render the three dimensions of things on a surface essentially two-dimensional. However, he does not reveal the source of the intuition of its importance, its pre-eminence; the idea that painting must not be a linear representation of the world, but rather its representation in volumes. One of the key points of his Treatise on Painting is that: "The painter follows these two objectives, man and the intention of his soul. The first objective is easy to reach, the second harder, because he must represent it by the movements of the members."

The Adoration of the Magi

Leonardo ended his Florentine period with a veritable manifesto of humanism. The unfinished Adoration of the Magi was the first painting he conceived in this radical — and even revolutionary — way.

The Renaissance already had a number of paintings on this subject, all of which had been painted in the narrative style. But Leonard chose to abandon narration, to represent instead the maelstrom of impression which had accompanied this major event of Christian history: the arrival on earth of the Son of God. Moreover, he deliberately ignored a logic that would impose on him only the presence of peasants or of Magi, or the union of both: he wanted to include the whole of humanity around the

The Adoration of the Magi, 1481/82

Study for the sleeve of the Virgin and Child with St Ann, See p.28

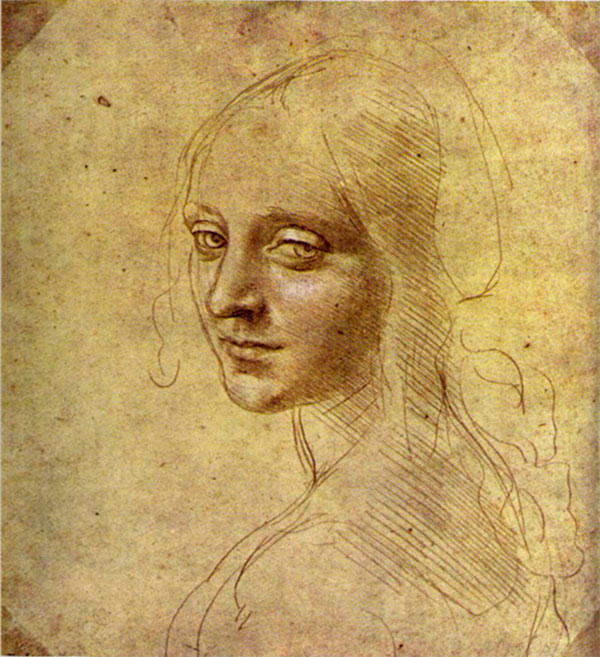

Study for the angel's head in the Louvre The Virgin of the Rocks (see p. 65)

Study of hands for Mona Lisa, seep .76

divine Infant. One critic has counted 66 characters... old men, young men, poets, soldiers, believers and non-believers.

This painting has a profound meditative quality. In it the rational meets the irrational. The background layers open on vast perspectives of far away horizons; the foreground figures reveal a complex repertoire of psychological attitudes of human relations and symbols. The mechanisms, the screws and springs of this pictorial machine are the figures, the gestures, the poses and his geometry the frame of mind, the attitudes and emotions. At the summit of the pyramid formed by the Virgin and the kneeling Magi is the Infant, the centre of this cosmogony. All around this young child, princes, shepherds, angels and knights move wrapped in this vast Epiphany — more revelation than simple adoration — such is the main idea of this composition.

Why did he believe that he had to introduce all these figures and elements into his compositions? One of the explanations that we can propose has to do with the profound feeling that Leonardo had for the bonds that unite all living creatures with Nature: trees, flowers, animals, men mingled and driven inexorably toward their destiny. Absolutely revolutionary, this was the most dramatic and the best-balanced composition of the whole Quattrocento, and the one in front of which generations of artists would lose themselves in an amazing contemplation.

The Virgin of the Rocks

The Virgin of the Rocks sings the victory of light over darkness. Here, Leonardo reconciled his imaginary universe with that of scientific naturalism. The painting is a mysterious revelation on a background which is not of this world: a grotto under an open sky where the Virgin takes refuge with Baby Jesus, St John the Baptist as a child, and an angel. But the figures have a supreme grace linked to a marvellous relaxed attitude, and the details of the vegetation are as close to nature as if they were from the hand of the best botanical painter.

The Virgin of the Rocks (detail), Paris

The Virgin of the Rocks, rich in allusions and symbols, which overflow the usual limits of the mind, reveals the most enigmatic aspect of Leonardo's character. What sense can we give to the enigmatic gesture of the angel, pointing to St John and not to Christ? The Virgin protects the Infant with her hand and seems to shelter him with a part of her cloak, is it St John, or perhaps humanity one sees instead, in its perpetual quest for divine protection? The centre of the composition is animated by a play of hands which has no equal in any work of art: one hand appears to protect, the others to worship, consecrate, and to indicate a mysterious point.

The characters are arranged in the usual pyramid, the Virgin's head forming once more the summit. Leonardo finally could express his ideal of beauty in the angel's face whose features do not any longer keep their shape according to a surface design, but seem to express its interiority. The grotto is immersed in a twilight atmosphere, veiled with a light mist of sfumato. The shaping of the subjects in sfumato is so delicate that the precise contours can hardly be perceived; faces and bodies materialise in the soft light which fall on them; and the shadows inside the grotto are so dense that they seem to possess their own substance. But the painting is not sombre and in spite of layers of varnish that soften its colours, they are always radiant.

Whatever the deep meaning of this work, and wherever and at whatever date Leonardo painted it, one fact certainly remains: it was his farewell to the Quattrocento. Having mastered the art of the Renaissance, he now went much further. Years would pass before he undertook another major work and, when he would decide to begin again, it would be to create one of the world's marvels, the first classical example of the Renaissance ideals at their highest: The Last Supper.

But before we come to The Last Supper, let us take a look at The Battle of Anghiari.

The Battle of Anghiari

The central design of the Battle of Anghiari is of hexagonal shape and represents a tangle of men and horses overlapping and so close to each other, that it seems as if it is the preparatory study for a group sculpture. The rearing horses are reminiscent of an early work of Leonardo, The Adoration of the Magi, but there is no longer an expression of joy and exuberance that is communicated, but a sensation of furious and cruel drunkenness: the warriors chop each other with their sabres while the beasts kick and bite. This painting can be considered the crystallisation of Leonardo's attitude toward war, which he called the pazzia bestialisima — the most bestial of madness — an opinion that his experience at the service of Caesar Borgia could only have reinforced. He wanted to transform The Battle of Anghiari into a terrible and timeless accusation and he succeeded by removing all background details. There is no decoration in the background and the fabulous costumes of the warriors do not belong to any precise period. To render the crystallisation more impressive, Leonardo directed all the lines of his composition — sabres, the men's faces, the horses curving bodies and outstretched hooves — toward the interior. Nothing distracts the eyes from this accusation, which stands here as convincing as the evidence that a prosecutor would place on a table.

Leonardo had worked long on his idea on the way to represent a battle; it is this very idea he is going to follow "You will first design the smoke of the artillery mixed in the air with the dust raised by the movement of the horses and the warriors", he wrote around 1490. "You will redden the faces, the people, the air, the gunmen, their neighbours, and this redness will go fading while it moves away from its cause... Arrows will go up in all directions, they will come down, will fly in straight lines, filling the air, and the bullets of the gunmen will leave behind a track of smoke... If you show a man falling to the ground, reproduce the marks of his sliding down on the dust transformed into a pool of blood; and all around, in the viscous earth you will show the

Copy after Leonardo's Battle of Anghiari, by Peter Paul Rubens

Copy after Leonardo's Battle of Anghiari, by Peter Paul Rubens

footprints of the men and the horses who went this way. A horse will drag his master's dead body leaving behind him, in the dust and the mud, the traces of the cadavers. Make the losers pale and dejected, the eyebrows high and frowning and the forehead lined with painful wrinkles... Men in flight will cry, mouth wide open. Put all kinds of arms under the feet of the warriors — broken shields, lances, broken swords, and all such similar things... The dying will grind their teeth, their pupils rolled upwards, beating their bodies with fists and their legs twisted. You will draw an unarmed warrior knocked down who, facing his enemy, bites and scratches him, in cruel and bitter revenge; there will also be a horse without his rider galloping among enemies, mane flying in the wind and causing huge damage with its hooves. Or someone crippled falling to the ground, covering himself with his armour and the enemy bending over him to administer the fatal blow. Or again a group of men slaughtered, flung down on the cadaver of a horse. Many conquerors will leave the battlefield; they will depart from the entanglement wiping with both hands, over their eyes and their cheeks, the thick layer of mud caused by tears and dust... Take care not to leave any flat spot which would not have been saturated with blood." In the Battle of Anghiari his idea on the way to represent a battle is made manifest.

The Last Supper

In 1495, at the request of Ludovico Sforza, Leonardo set about painting the Last Supper on the wall of the dining room of the convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie, in Milan. For about 15 years Leonardo had been reflecting on the ideas which he developed in The Last Supper. And so, The Last Supper gave the artist the opportunity to test his idea that painting is something mental, and to achieve in a single piece of art, a synthesis of his vast experience in the optical domain, in musical harmony, in the fields of anatomy and architecture, in the realms of colour and perspective, as well as in the domains of matter and technique.

During the year when he worked on The Last Supper, the painter's life became an inner adventure. It took Leonardo almost three years to paint this huge, obsessing project, which did not leave his thoughts for a moment. The Italian writer, Matteo Bandello, a student at the priory at the time of The Last Supper, watched Leonardo working and described it thus: "He would arrive at the convent at dawn. Quickly climbing the scaffolding, he worked without resting until the night's shadow would force him to stop, without the least thought for food, so much absorbed by his work. At other times he would stay three or four days without touching a brush and would spend hours in front of his painting, arms crossed, looking carefully at its subjects, as though criticizing his own painting."

This painting is not only prodigious in itself but later had a great influence. There is an aspect so evident in this masterpiece that it is often overlooked. In art few compositions offer so many difficulties as the presentation of thirteen subjects seated at a long table. Under Leonardo's brush this difficulty has been so majestically overcome that it is not seen. One does not even think about it.

He cleverly placed familiar objects around the disciples so that he would not have recourse to imaginary outdated modes. The wall on which he was painting occupied one of the short sides of the long room of the refectory of the convent. In front of the opposite wall, the prior's table was placed on a platform; all along the room there were rows of tables for the monks. The painting reproduced the tablecloths, knives, forks and the monk's glasses. In Leonard's mind, Christ had to nourish himself, in this company, with the same food as the mortals. When the painting was completed, in 1498, those who were invited to contemplate it must have thought they were the object of a hallucination: the monks' room had become the extension of The Last Supper.

Another difficulty was the necessity to isolate Judas, in such a way that he could be recognized at first glance. For a thousand years, in fact from the first expression of Christian art, this problem was solved by placing Christ and the eleven faithful

The Last Supper.

The traitor Judas, the fourth from left, with his right hand clutches the pouch containing the money he has been paid to betray Christ.

The Last Supper. The traitor Judas, the fourth from left, with his right hand clutches the pouch containing the money he has been paid to betray Christ.

disciples on one side of the table, facing forward, with Judas on the other side. Artists, at the beginning of the Renaissance, broke off with the traditional representation of the religious themes. But generally speaking they could not discover other solutions to the presentation of the disciples. To isolate Judas, Leonardo found, at least apparently, an easy solution. He placed Judas on the same side of the table as the other disciples, but isolated him from them by his expression: psychologically making him an outsider. And this isolation is infinitely more poignant, clearer than a simple physical separation. Sombre, staring fixedly, Judas keeps himself away from Christ, forever a prisoner of his remorse and his solitude. The disciples question, address reproaches to themselves, forgive themselves and do not yet know who among them has betrayed Christ: but one who contemplates The Last Supper recognises the traitor at first glance. The only one, who is spared this wave of emotion breaking all around, is Christ. An aura of peace floats around him, space isolates him and indicates that he is at the centre of the event as well as of the painting.

In its complexity The Last Supper expresses perhaps better than any other work of Leonardo, the master's innovations: the naturalness of the poses and the harmony with the psychological content; the insertion of each individual in a dynamic web of correspondence and contrasts, in an emotion which is indicated by the position of the hands and the movement of the heads; the psychological and not any longer the geometrical perspective, which enliven the scene in space and in the real light of the room. Tradition asks one to interpret the work as if Christ had just uttered the sentence: "One of you must betray me", and says that Leonardo wished to fix forever this dramatic moment. The disciples deeply reacted to these words: a superb show of attitudes and gestures which reveal "the intentions of their souls."

It is assumed that the faces, except for that of Christ were those of people who Leonardo found in Milan or in the vicinity. Leonardo spent so many hours wandering in the haunts of the ruffians of Milan searching for the right Judas that the prior of Santa Maria delle Grazie complained to the Duke of Sforza that

the work was going too slowly. Leonardo replied that he was having a hard time finding a Judas. But, if they insisted that he go ahead with his work, he could use the prior's head, which would perfectly suffice. In fact, for Jesus he had two models in mind, but finally, the Christ became an abstraction not a portrait; a figure profoundly moving and universal.

As soon as The Last Supper was revealed, Leonardo's contemporaries were stunned by the brutal revelation of reality. In one stroke, the traditional methods became obsolete and painting entered a new phase of its history. All references from that time agree in saying what admiration this piece aroused.

The unfortunate destiny of this prodigious composition, in which Leonardo gave the best of himself and dared to use an experimental technique, resulted in disaster. It was not long before The Last Supper began to deteriorate. If it is famous today, it is because of the number of copies that were made in the XVIth century, some by Leonardo's direct disciples, which permit us to guess more or less what the original was like; notably the details and the colours and at the same time, to appreciate its incredible radiance. A series of restorations and wars, ending in the bombing of 1943, have reduced this masterpiece to a ghost-like state.

Mona Lisa

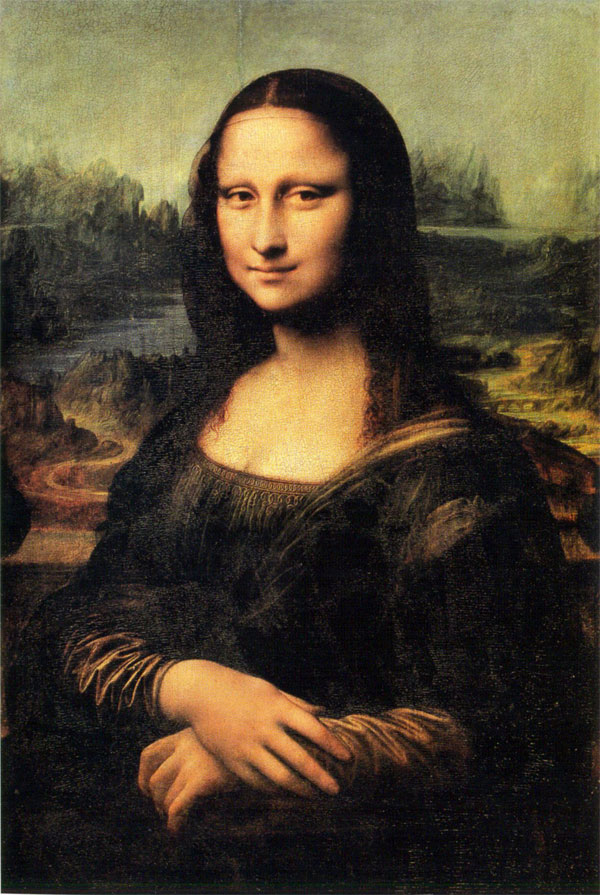

One of the worlds best loved paintings carried two names: Mona Lisa, a short form of Madona Lisa, the third wife of a Florentine merchant, and La Joconde, taken from the merchant's name, Francesco de Giocondo.

The first time Madona Lisa posed for Leonardo, she was twenty-four years old. To the eyes of her contemporaries she was approaching maturity. As a portrait, this work was an admirable success, "an exact copy of the subject", thought Vasari. But Leonardo far transcended the realistic portrait to make of his subject not only a woman, but the Woman. Under his hands, the individual and the symbolic became one. The idea that the artist

Portrait of Lisa del Giocondo (Mona Lisa), 1503-1506 and later (1510?)

St John the Baptist, c. 1513-1516?

had of the Woman as symbol does not coincide with that of most men. Leonardo portrays her with an absence of sensuality quite disconcerting, in fact making her appear at the same time voluptuous, cold and admirably beautiful.

The painting is of modest dimensions, but it feels monumental to the viewer, due to the effect achieved by setting the model in relation to the background of the portrait. This monumental effect further increases the impression of charm and coldness that Mona Lisa radiates. For centuries she has been contemplated with delight, astonishment, or with a feeling of awe. Technically, Leonardo brought to the peak of perfection the use of sfumato; it is not known how many layers of extreme thinness — perhaps as many as one hundred — play their role in the sfumato. The background is without any doubt the most beautiful of all Leonardo's paintings. The details are precise but the jagged rocks, the water, the bones and blood of the earth bring to mind a romantic vision of earth the day after the Creation. This painting has had such an influence on art that it is quite difficult to look at it with fresh eyes.

The Mona Lisa was an immediate success. From the time of its creation, people started to imitate and copy it, in France, in Italy, in Flanders, and in Spain. There are dozens of copies of this work, painted between the XVIth and the XIXth centuries. Its glory has never faded.

St John the Baptist

No matter how troubling it is, this tender face with a provoking smile is that of St John, just as Leonardo had wanted to interpret it, contrary to the traditional character of the ascetic, emaciated and full of fire. It is certain that by giving him this smiling and graceful pose, Leonardo had wanted to express the quintessence of the eternal mystery of which we find the signs in such a great part of his work — the enigma of Creation and of life itself.

The St John the Baptist reaches perfection in its fluidity and transparency. It seems that one cannot go further in the representation of the immaterial by the balance of shadow and light, of the concrete and the evanescent. This work which is more an apparition than a picture, also possesses the ring of ultimate success. The raised index finger of St John the Baptist would remain a prodigious affirmation, even if it was not pointing at anything in particular.

* * *

To Leonardo the question was always to know how the world is made and since this can never be ably resolved, he did not dare to ask others. Painting, a mental subject was, for him, a certain way to know and evidence of the knowledge acquired. He would never have said that it is a manual craft; he preferred it to sculpture, precisely because the latter seemed to him more manual and less mental. Even when he wrote about machines and tools, he more readily said: "I know the way to..." than: "I do...". Art aims to render the individuality of the model, and, for that, it searches behind the lines that can be seen, for the movement the eye does not see, behind the movement itself, to something still more secret, the original intention, the fundamental aspiration of the subject. "The artist", he says, "has first the universe in mind, then in the hands." To him, science was not the only way to gain the knowledge of the world, but again neither the richest nor the truest of it. "Painting embraces all forms of Nature... You have the effects of the manifestation, we have the manifestation of the effects. In art, we can be said to be God's grand children."

Leonardo was a painter: painting was his philosophy. In fact he said it himself, and he spoke of painting as one speaks of philosophy. That is, he related everything to it. He had excessive ideas about painting, even a peculiar turn of thought which is far from satisfying the whole intelligence.

He felt with an intense suffering the constraint of time, and, in one page of the Codex Atlantica, he let out this moan, the

The Virgin of the Rocks, London

distressing cry of a man who feels that life escapes him, and with life, action. "Oh time, consumer of things, and oh you, envious old age which destroys everything." To surmount the anxiety of impermanence and this sensation at once physical and intellectual, of time, Leonardo took refuge in the pursuit of the eternal. Not in the metaphysical concept of eternity, but in the representation of something eternal: light. "Immerse everything in light, it is immersing them in the infinite", one reads in the Leicester Manuscript. The problem of expression and representation of light becomes the major concern of the painter. In the domain of science and practical action, he knows very well that everything is devoured and nibbled by time; only in a work of art can beauty last, under one condition, that it contains the essence of infinity and eternity: light. Then the great miracle is accomplished. The subjects which represent perishable beings become infinite and eternal by wrapping themselves in this mysterious luminosity which transposes them into other dimensions, into a world devoid of the sad bonds of death and old age. "Beautiful mortal things go and do not last", it is written in the Forster Manuscript, but the privilege of art, beyond everything, is to confer a kind of immortality to the mortal element by associating it to light, dissolving it in light. In this Leonardo was also a forerunner.

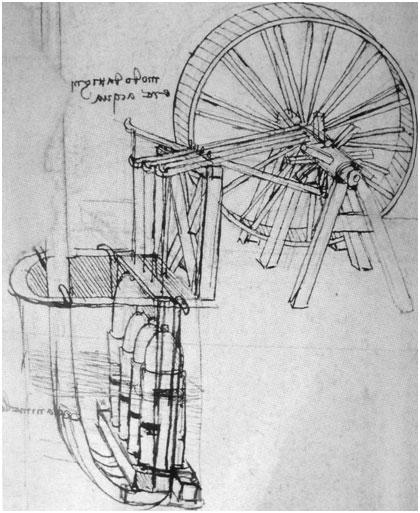

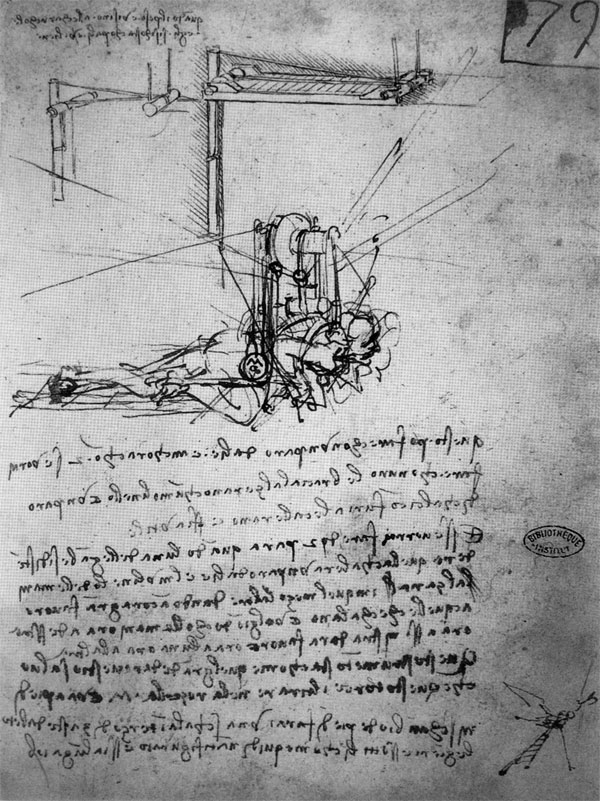

Study of a hydraulic device.

Leonardo's applied mechanics, perhaps more than any other of his scientific or technical pursuits, strike sparks of recognition and admiration in the machine-conscious 21th Century mind.

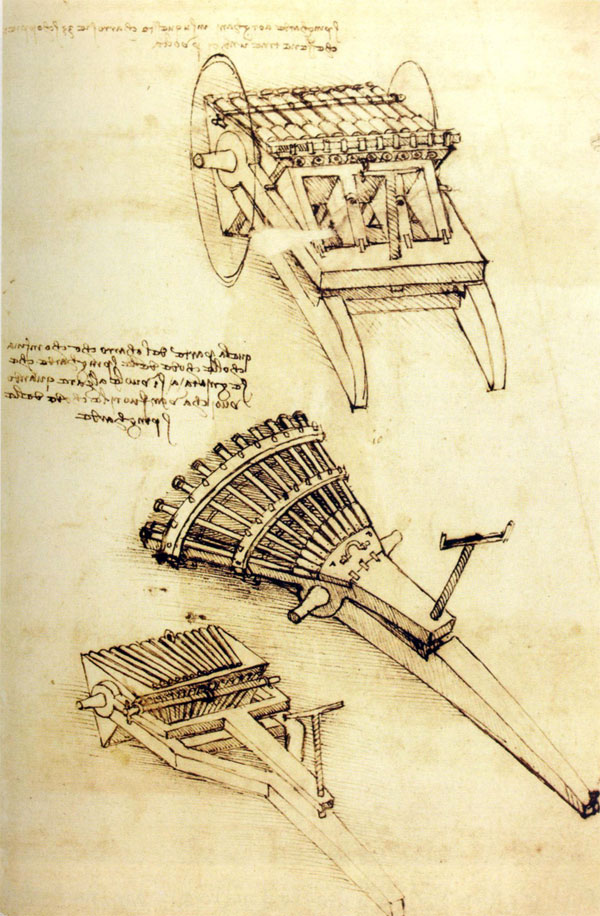

Sheet of Studies with multi-barrelled guns, c. 1482

Study of a flying Machine with a Hand and Foot-Powered mechanism 1487-1490

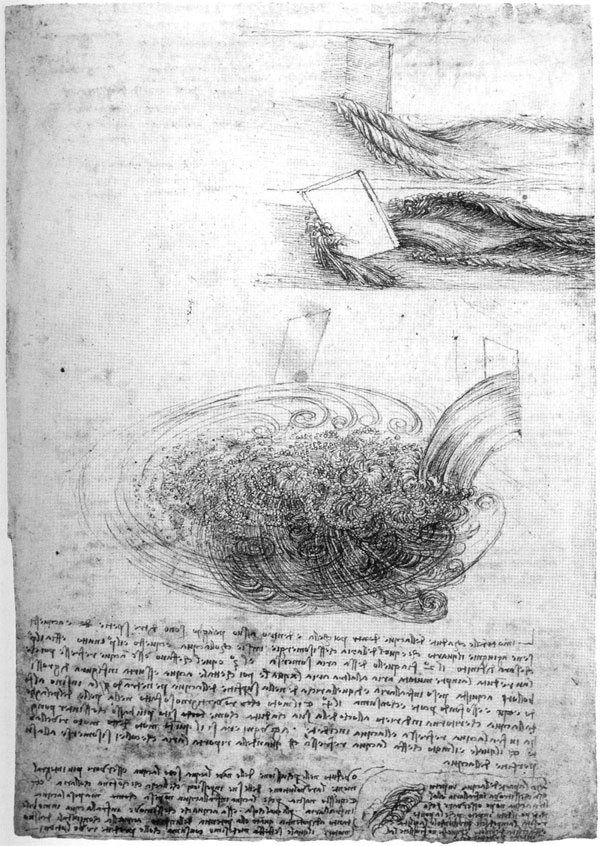

Studies of water formations, c. 1507

Leonardo's superhuman quickness of vision is shown in these sketches of flowing water - at top as it swirls around impeding boards, then below as it rushes into as pool.

Related Books

- Alexander the Great

- Arguments for The Existence of God

- But it is done

- Catherine The Great

- Danton

- Episodes from Raghuvamsham of Kalidasa

- Gods and The World

- Homer and The Iliad - Sri Aurobindo and Ilion

- Indian Institute of Teacher Education

- Joan of Arc

- Lenin

- Leonardo Da Vinci

- Lincoln Idealist and Pragmatist

- Marie Sklodowska Curie

- Mystery and Excellence on The Human Body

- Nachiketas

- Nala and Damayanti

- Napoleon

- Parvati's Tapasya

- Science and Spirituality

- Socrates

- Sri Krishna in Brindavan

- Sri Rama

- Svapnavasavadattam

- Taittiriya Upanishad

- The Aim of Life

- The Crucifixion

- The Good Teacher and The Good Pupil

- The Power of Love

- The Siege of Troy

- Uniting Men - Jean Monnet