Lenin - Chapter III

Chapter III

Even though Lenin returned to Russia only after the February Revolution in 1917, having been in exile since 1900, he nevertheless had an enormous influence and led the October Revolution. Few other émigré revolutionaries had Lenin's firmness and self-confidence, strength of vision and decisiveness for Russia's future. Lenin's great strength was an ability to organise the party — and much of this had to be done in secret before October 1917. Getting things done was Lenin's main quality and he got things done as a result of meticulous organisation.

In 1917, Russia, war-weary and desperate with cold and hunger, did away with tsarist rule. This revolution broke out spontaneously on 23rd February, 1917, without definite leadership and formal plans; it seemed that the Russian people had had enough of the existing system. Petrograd,1 the capital, became the focus of attention, and, on this date, people at the food queues started a demonstration. Many thousands of women textile workers who had come out of their factories — it was International Women's Day but largely as a protest against the acute shortages of bread — joined the demonstrators. Mobs marched through the streets, shouting slogans

1. Saint Petersburg was founded by Tsar Peter the Great on May 27 (Julian calendar) 1703. From 1713 to 1728 and from 1732 to 1918, it was the Imperial capital of Russia. In 1914 Saint Petersburg was named Petrograd and in 1918, the capital shifted to Moscow. Petrograd was named Leningrad in 1924. Since 1991, it is again Saint Petersburg.

such as "Bread!" and "Give us bread!" Large numbers of men and women were on strike and by 25th February everything had virtually shut down in the city. Police lost control on the situation as students, white collar workers and teachers joined the workers in the streets. Soldiers mutinied and there was near total breakdown of military power and collapse of civil authority. Seeing the demonstrations on such a massive scale, the cabinet resigned as calls went out to replace them with responsible members. Nicholas fearing for his life admitted defeat finally and abdicated on 2nd March, ending the 300 year rule of the Romanov dynasty.

Lenin, then in Switzerland, read about the Revolution occurring in the newspapers, when the first news of the revolution reached on 15th March.1

Stunned and delighted, Lenin and Nadya read the reports...There really could be no doubt: Revolution had occurred. ... This time monarchy had been blown away.2

Lenin's return home was imperative now. But that was a difficult task in the middle of the First World War. Switzerland was surrounded by the warring countries of France, Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy. Finally, on the evening of 3rd April, 1917, Lenin arrived in Petrograd (it is believed he transited through the front in a sealed train with the secret help of the German officials to pass through their territory), and he on arriving:

... finally saw the Russian masses as they really were and witnessed what Nadya called "the grand and solemn beauty of the Revolution" in all its visceral power and immediacy — an experience he had missed in 1905. "Yes," he whispered under his breath, as he emerged out onto the square packed with thousands of eager faces:

- According to the Gregorian calendar.

- Robert Service, Lenin: A Biography, p. 254.

Lenin's voyage back to russia: Lenin and his fellow travellers in Stockholm, days after disembarking from the sealed train across Germany. The woman in the large bonnet following Lenin is his wife Nadya.

Lenin's voyage back to russia: Lenin and his fellow travellers in Stockholm, days after disembarking from the sealed train across Germany. The woman in the large bonnet following Lenin is his wife Nadya.

Picture taken of Lenin for his offical documents with which to escape to Finland

"Yes, this is the revolution."1

Lenin's return was greeted by the Russian populace, as well as by many leading political figures, with great rapture and applause. His arrival was enthusiastically awaited, and a large crowd of supporters thronged to greet him and cheered as he stepped off the train. He was carried shoulder-high from the platform to the station hall.

The atmosphere was electric; the sense of euphoria palpable. "Just think," recalled an exhilarated Feodosiya Drabkina2 of that memorable night, "in the course of only a few days Russia had made the transition from the most brutal and cruel arbitrary rule to the freest country in the world."...

As the crowd rumbled in excitement, with sailors and soldiers hurling their caps in the air for joy, only a few fractured words of Lenin's speech penetrated the crowd. The people needed three things — peace, bread, and land. They must "fight for the social revolution, fight to the end, till the complete victory of the proletariat." And then, amid the clamor, one distinctive Leninist phrase was hurled at the crowd... "Long live the worldwide socialist revolution!"3

Following the February revolution, Russia was under dual power of the Provisional Government (the temporary government that replaced the tsar) and the Petrograd Soviet (an influential local council representing workers and soldiers in Petrograd). The two groups coordinated with each other on major issues but were often at odds with each other. Lenin to the shock and surprise of everyone condemned both the Provisional Government and the Petrograd Soviet for their ideologies and policies. At an impromptu meeting

- Helen Rappaport, Conspirator: Lenin in Exile, pp. 299-300.

- A Russian revolutionary underground worker.

- Ibid., pp. 300-1.

of party members later that night Lenin asserted that the only way to end the war was to overthrow the Provisional Government — the Provisional Government had taken the major decisions of remaining in the war and postponing the land reforms — and form a soviet government by soldiers, peasants and workers.

Among those listening to Lenin's two-hour tirade was a Menshevik, Nikolay Sukhanov, who had slipped past the Bolshevik guards. "I shall never forget that thunderlike speech...," he wrote. "It seemed as though all the elements had risen from their abodes, and the spirit of universal destruction, knowing neither barriers nor doubts, neither human difficulties nor human calculations, was hovering round... above the heads of the bewitched delegates."1

Lenin called for a new revolution; the Bolsheviks should press ahead to a revolution of the workers and the peasants and not rest content, like almost all other Russian socialists, with the "bourgeois" February Revolution. He reiterated that the country was still at war and the new government had failed to give the people bread and land. He gave several speeches in the days following his arrival, calling for the overthrow of the Provisional Government. April Theses was the name given to the publication of the collection of speeches given by Lenin during those days. Pravda (Truth), the Bolshevik newspaper, on 7th April , published the ideas contained in those speeches.

Apart from a short period in 1905, Lenin had spent 15 years as an émigré abroad. Yet:

His sense of the real, his intimate understanding of the living and toiling worker had not weakened during these years at all; on the contrary, through theoretical study and his creative imagination it had become even

1. The World in Arms, History of the World, Time-Life Series, p. 65.

more solid. From episodic and accidental encounters, from observation whenever an opportunity occurred, Lenin gathered details which allowed him to build up a whole.

However, it was as an émigré that he spent those years of his life during which he finally acquired the stature to play his future historical role. When he arrived in Petersburg, he brought with him those revolutionary conclusions which summed up all his social-theoretical work and all the practical experience of his life. He proclaimed the watchword of socialist revolution the minute he touched the soil of Russia. But only then, face to face with the awakening working masses of Russia, all the accumulated knowledge, all that had been pondered, and all that had been resolved, went on practical trial. The formulae stood the test. Moreover, only here in Russia, in Petersburg, in daily life, they took on a concrete irrefutable shape and consequently an irresistible force... The entire reality asserted itself with the full voice of the revolution. And here Lenin demonstrated — or perhaps he himself realized it fully for the first time — to what degree his ear was attuned to the still discordant clamour of the awakening masses. With what profound, almost organic, contempt he viewed the mice-like scurrying of the leading parties of the February revolution, and the waves of 'powerful' public opinion beating upon one newspaper and another; with what scorn he looked at the short-sighted, self satisfied, babbling official Russia of the February days! Behind this stage hung with democratic props, he heard the rumble of events on quite a different scale. When the sceptics were pointing to all the difficulties of his enterprise, to the mobilization of bourgeois public opinion, to the simplicity of the petty-bourgeoisie... He saw and he understood the difficulties just as well as did the others; but he also had the almost physical awareness — as if

it were tangible — of the gigantic historical forces pent up and now ready for the tremendous burst which was to overcome all obstacles.1

In his April Theses, he argued that the country was passing from the first stage of the revolution to its second stage. The first stage owing to the insufficient class-consciousness and organisation of the proletariat, placed power in the hands of the bourgeoisie; it must now place power in the hands of the proletariat and the poorest sections of the peasants — "All power to the soviets" was his slogan. He advocated non-cooperation with the liberals (i.e. non hard-line Communists) and an immediate end to the war. The April Theses was more radical than anything his fellow revolutionaries had heard before and invited a great deal of controversy.

Trotsky describes Lenin and that moment in history thus:

... Lenin invariably seemed extremely preoccupied —under the apparent calmness and his usual matter-of-fact behavior one could sense a tremendous inner tension. At that time the Kerensky regime seemed all-powerful. Bolshevism seemed a quantite negligeable. The party itself was not yet aware of its gathering strength. And yet Lenin was leading it, unfalteringly, towards momentous tasks...

His speeches at the First Congress of the Soviets surprised the Social Revolutionary and the Menshevik majority and provoked their anxiety. Confused, they sensed that this man was aiming very, very high. But they did not see his goal. And the petty-bourgeois revolutionaries wondered: What is he? Who is he? Simply a madman or a historical missile endowed with an unheard of explosive force?

... he made the impression of someone who had not as yet said all he had to say, or who said it not quite as he

1. Leon Trotsky, On Lenin, pp. 77-8.

wished to... At that moment an extraordinary breath of air drifted over the hall: it was the blast of the wind of future change felt by everybody, while bewildered eyes anxiously followed Lenin's figure, so ordinary and so enigmatic.1

At first his was a lone voice and his resolute and uncompromising stand isolated Lenin and the Bolsheviks. Lenin, however, worked ceaselessly and within a few months with the powerful slogans of `Peace, land and bread,' he began to win over the Russian people no longer able to bear the crushing burden of war and poverty, and steadily the popularity of the Bolsheviks increased.

In July this popularity manifested in a pro-Bolshevik uprising known as the July Days. There were demonstrations against the Provisional Government and riots resulting in many deaths. However, the government responded with a heavy hand against the Bolsheviks and Lenin was accused of being a German spy. Pravda was closed down and several leaders arrested. Lenin had to go into hiding again as the Bolshevik central committee feared for his life. Russia plunged into further chaos as lawlessness and disorder gained ground. There was a threat of a coup by the right-wing, which brought a fresh upsurge of support for the Bolsheviks and they won control over the Petrograd and Moscow soviets.

By September 1917, Lenin believed the Russian people were ready for another revolution and exhorted the Bolshevik central committee to make preparations. "...he was acutely aware that there was no time to be lost. It is impossible to maintain a revolutionary situation at will until such moment as the party is ready to make use of it."2

"History will not forgive us," he declared, "if we do not seize power now."3 However, the central committee decided to wait —there were differences within the party itself — and it was only at a secret meeting of the Bolshevik leaders on 10th October, that he successfully convinced the others that it was time for an armed

- Leon Trotsky, On Lenin, p. 70.

- Leon Trotsky, Ibid., p. 81.

- The World in Arms, History of the World, Time-Life Series, p. 86.

uprising. The date of 24th October was tentatively fixed and it was agreed that the Military Revolutionary Committee (MRC) that had been formed would arrange the details of the uprising. However, all would have been lost when on that date the government suddenly took action and declared the MRC illegal; orders went out for Trotsky and other Bolshevik leaders to be arrested. Lenin from his secret hideout made a last minute appeal to the central committee:

With all my power 1 wish to persuade the comrades that now everything hangs on a hair... We must at all costs, this evening, tonight, arrest the ministers... We must not wait!! We may lose everything...1

In the early hours of 25th October, the revolution began. The October Revolution led by Vladimir Lenin, was far less sporadic than the revolution of February and came about as the result of deliberate planning and coordinated activity to that end. The Revolution of October 1917 is a classic example of how Lenin and Trotsky worked together.

Leon Trotsky had joined the Mensheviks in the 1903 split; a year later in 1904 he left the Mensheviks describing himself a "non-factional social democrat". During the years leading up to 1917, he occupied himself with trying to bring the differing factions together and in the process clashing with many prominent members of the party including Lenin. Later he admitted that he had been wrong to oppose Lenin on the issue of the party. He had spent ten years as an émigré revolutionary in Europe and America, before returning to Russia in March 1917 where he assumed control of a Menshevik group that sided with the Bolsheviks.

Lenin's organizing skills — he understood the minutest details — combined powerfully with Trotsky's skills as a military leader, his rousing oratory and his devotion to the revolution. The planning for the revolution was done by Lenin and the actual execution of what Lenin had planned was carried out by Trotsky. This

1. Ibid., p. 66.

combination infused the rest of the party with enthusiasm and vigour which was vital at that point and during the critical time that immediately followed the Bolsheviks rise to power in Russia. However, none of this would have been meaningful, if the Bolsheviks had not offered the people what appealed to them. Lenin's message of "Peace, bread and land" found widespread acceptance.

Describing Lenin's, role during the Revolution of 1917, Trotsky has said the following:

One has to learn not to lose one's breath in the rush of revolutionary events. When the tide is flowing strongly, when the forces of revolution are automatically gathering strength, and the forces of reaction are scattering and fritter away, then there is the great temptation to let oneself be carried by the elemental power of the mighty wave. Success too quick may be as dangerous as defeat. Not to lose sight of the guiding light of events; after each new success to tell oneself: nothing has been achieved yet, nothing made quite secure; five minutes before final victory to act with the same vigilance, the same energy and the same tenacity with which one acted five minutes before the beginning of the military operations; five minutes after victory, even before the first triumphant applause has sounded, to remind oneself: What has been conquered has not yet been secured and no time must be lost — such was the attitude, such was the manner and such was the method of Lenin; such was the organic essence of his political character and revolutionary spirit.1

On 24th October troops loyal to the Bolsheviks took up crucial positions in the city. Sporadic violence took place on the night of 24-25. By the 25th October every key building in St. Petersburg was under Bolshevik control, except the Winter Palace where Kerensky2

- Leon Trotsky, On Lenin, p. 90.

- The Provisional Government was led by Alexander Kerensky.

and the other Ministers remained with a small guard. The Provisional Government had been overthrown by Vladimir Lenin, leader of the Bolshevik Party, along with the workers' Soviets on 25th October 1917, (of the Julian calendar which Russia was using at that time). At the emergency meeting of the Petrograd Soviet, Trotsky made the historic announcement, that the power of Kerensky had been overthrown and that a socialist administration would now assume power.

Lenin, now chairman of the Bolshevik cabinet — the Council of People's Commissars — addressed the All-Russian Congress of Soviets. Lenin attending the meeting undisguised for the first time stood up to speak to "a thundering wave of cheers". According to the American journalist John Reed, Lenin waited for the applause to subside before declaring simply: "We shall now proceed to construct the Socialist order!" There was thunderous applause again. Reed described the man who appeared at about 8:40 pm:

A short, stocky figure, with a big head set down in his shoulders, bald and bulging. Little eyes, a snubbish nose, wide, generous mouth, and heavy chin; clean-shaven now, but already beginning to bristle with the well-known beard of his past and future. Dressed in shabby clothes, his trousers much too long for him. Unimpressive, to be the idol of a mob, loved and revered as perhaps few leaders in history have been. A strange popular leader — a leader purely by virtue of intellect; colourless, humourless, uncompromising and detached, without picturesque idiosyncrasies — but with the power of explaining profound ideas in simple terms, of analysing a concrete situation. And combined with shrewdness, the greatest intellectual audacity.1

Soon after, Lenin proceeded to propose a Decree on Peace and a Decree on Land which were passed by the Congress.

While Lenin was undisputed political leader, Trotsky was a close

1. John Reed, Ten Days That Shook the World, London: Penguin (1977), p. 128 (Available online, courtesy of the Marxist Internet Archive).

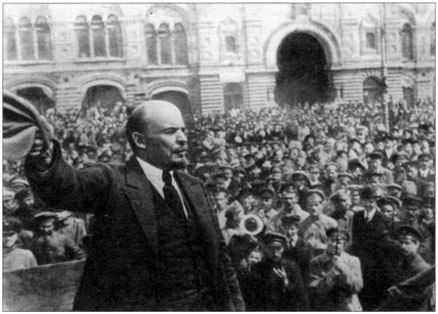

Lenin making a speech in Moscow

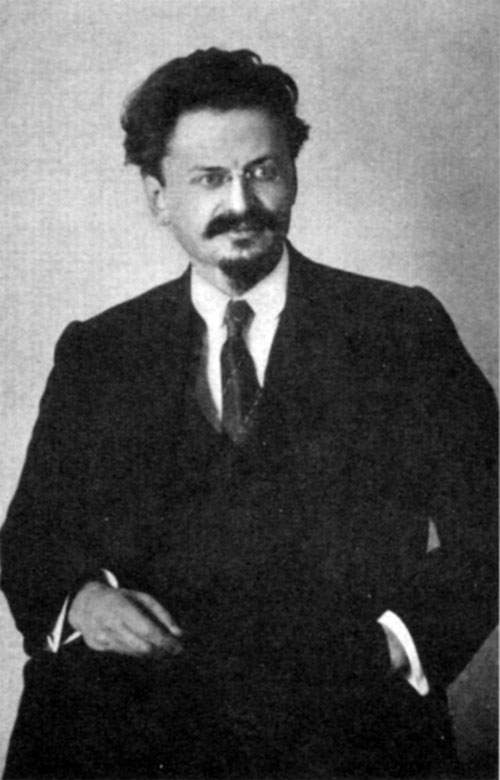

partner, leading the Petrograd Soviet and its Military-Revolutionary Committee. It is the MRC which stormed the Winter Palace and ejected the liberal Provisional Government of Alexander Kerensky. Morgan Phillips Price, an Englishman, sent to report for the Manchester Guardian in 1917, watched the Bolshevik leaders, Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky, very closely during this period. He wrote the following:

Lenin struck me as being a man who, in spite of the revolutionary jargon that he used, was aware of the obstacles facing him and his party. There was no doubt that Lenin was the driving force behind the Bolshevik Party... He was the brains and the planner, but not the orator or the rabble-rouser. That function fell to Trotsky. I watched the latter, several times that evening, rouse the Congress delegates, who were becoming listless,

Leon Trotsky

Leon Trotsky

probably through long hours of excitement and waiting. He was always the man who could say the right thing at the right moment. I could see that there was beginning now that fruitful partnership between him and Lenin that did so much to carry the Revolution through the critical periods that were coming.1

Leon Trotsky describes Lenin's style of speaking:

... But a line of intense and powerful thought cuts its way surely and clearly through these cumbrous phrases.

Is the speaker really a profoundly educated Marxist, thoroughly versed in economic theory, a man of enormous erudition? It seems, now and again rather, that here is a self-educated man who has arrived at an extraordinary degree of understanding all by himself, by an effort of his own brain, without any scientific apparatus, any scientific terminology, and now expounds it all in his own manner. How is it that we get such an impression? Because the speaker has thought out things not only for himself, but also for the broad masses; because his own ideas have been filtered through the experiences of these masses and in the process have become free of theoretical ballast. He can now construct his own exposition of problems without the scientific scaffolding which served him so well when he approached them first himself...2

Lenin's speeches are characterized by what is so essential in all his activity: the intentness on the goal, his purposefulness. The speaker is not out to deliver an oration, but to guide towards a conclusion which is to be followed by action.3

- Price was sent to Petrograd and reported on the overthrow of Tsar Nicholas II.

- Leon Trotsky, On Lenin, p.139.

- Ibid., p.141.

Related Books

- Alexander the Great

- Arguments for The Existence of God

- But it is done

- Catherine The Great

- Danton

- Episodes from Raghuvamsham of Kalidasa

- Gods and The World

- Homer and The Iliad - Sri Aurobindo and Ilion

- Indian Institute of Teacher Education

- Joan of Arc

- Lenin

- Leonardo Da Vinci

- Lincoln Idealist and Pragmatist

- Marie Sklodowska Curie

- Mystery and Excellence on The Human Body

- Nachiketas

- Nala and Damayanti

- Napoleon

- Parvati's Tapasya

- Science and Spirituality

- Socrates

- Sri Krishna in Brindavan

- Sri Rama

- Svapnavasavadattam

- Taittiriya Upanishad

- The Aim of Life

- The Crucifixion

- The Good Teacher and The Good Pupil

- The Power of Love

- The Siege of Troy

- Uniting Men - Jean Monnet