Lenin - Chapter I

The Ulyanov family in 1879, from let to right: (standing) Olga, Alexandr, Anna; (Seated) Maria Alexandrovna with daughter Maria, Dmitri, Ilya Nikolaevich and Vladimir.

Vladimir ilyich ulyanov

(1870-1924)

CHAPTER I

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov was born in 1870, on April 101, in Simbirsk, a town on the river Volga, that later was in his honour called Ulyanovsk. He adopted in 1901 the last name Lenin — a name that is said to have been derived from the Lena, the longest river in Siberia. It was the main — one in a series of many — pseudonyms that he was obliged to use while undertaking revolutionary activities in Europe. His family was well-to-do, and Lenin, the third child was close to his parents and the other five siblings.

His parents both educated and highly cultured, encouraged a passion for learning in their children, especially Lenin who was a voracious reader and finished with a first position in his high school, leaving school with a gold medal for his exceptional performance. He decided that he wanted to study law at Kazan University.

In spite of his well-to-do background and a comfortable life during his school years, the rest of his life did not prove to be easy for Lenin and his family. His father passed away in 1886, and then a tragic event happened in 1887 that had a profound effect on his life;

1. (April 22). Russia till February 1918 used the Julian calendar, while the Western world used the Gregorian calendar which is in use today. During the nineteenth century the Julian calendar fell 12 days behind and, in the twentieth century it fell 13 days behind the Gregorian calendar. Generally, all dates cited by historians for pre-revolutionary events are according to the Julian calendar.

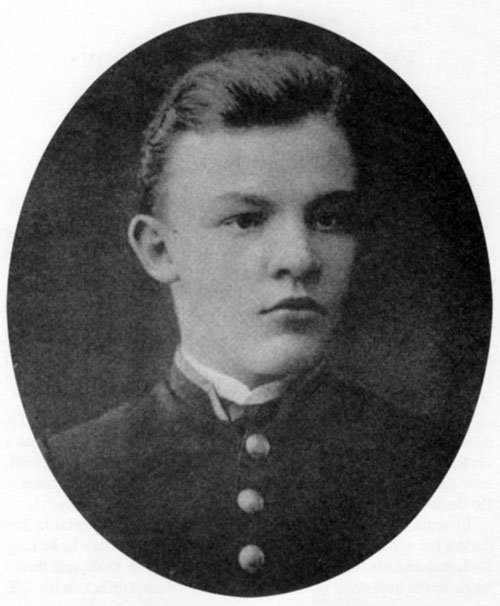

Vladimir Ulyanov, aged seventeen

Aleksandr, his older brother, who was a university student at the time, was arrested and hanged for being a part of a group planning to assassinate Emperor Alexander III. Aleksandr's involvement in political activism against the autocracy was not an isolated incident in Lenin's family. In fact, all of Lenin's siblings would take part to some degree in revolutionary activities. Lenin gained an interest in revolutionary leftist politics following his brother's execution and the same year enrolled at Kazan University to study law. However, he did not stay there for long, as during his first term, he was expelled for taking part in a student demonstration. After one protest demonstration he was arrested and taken to the police station. One of the police officers asked: "Why are you rebelling, young man? After all, there is a wall in front of you." Lenin confidently replied: "The wall is tottering, you only have to push it for it to fall over."

He was put under police surveillance and exiled to his grandfather's estate in the village of Kokushkino, where he stayed along with his sister Anna, who too had been ordered by the police to live there as a result of her own suspicious activities. Here, Lenin's political education began. His main activity was self-education, an intellectual self-preparation. He plunged into the study of radical literature; a novel that made a deep and lasting impact on him was, What Is To Be Done? by Nikolai Chernyshevsky, a story of socialists living in communes and of an activist's total dedication to revolutionary politics. Lenin began the study of the works of the German philosopher, Karl Marx, who was to influence him deeply. His famous book Das Kapital would affect Lenin's thinking enormously and by 1889 he was a committed Marxist.

With his family Lenin left for the city of Samara where he obtained permission to continue his studies away from the university. Being used to studying on his own, this posed no problem for him and finally in 1892, he received his law degree from the St. Petersburg University, achieving great success. He received the highest possible grade in every subject and was the only student that year to do so. He began to practice law and most of his clients being peasants and Russians from the poorer section of society gave him a further insight into their struggles with the existing legal system.

Lenin dedicated himself to becoming a revolutionary and revolutionary politics became his prime focus. In 1893 he moved again, choosing St. Petersburg, the Russian capital at the time, for his residence. There, Lenin made contact with other Marxists through a network of informal discussion groups, and participated in their activities. In 1895, Lenin made the first of many trips abroad primarily to make contact with some of the leading Marxists who were living in exile, in particular Georgy Plekhanov,1 considered the father of Russian Marxism, by whom he was greatly inspired. After he visited Switzerland in 1895, one of his hosts wrote the following about him:

I felt that I had before me a man who would be the leader of the Russian Revolution. He was not only a cultured Marxist — of these there were many — but he also knew what he wanted to do and how to do it.2

Back in St. Petersburg he continued with his political agitation, becoming soon a senior figure within the League of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class3 which had just been established. Lenin wrote a number of essays and pamphlets; in fact, he was a prolific writer, and he also regularly delivered lectures on Marx's Das Kapital, besides smuggling seditious literature into Russia. These activities had come to the notice of the authorities and finally they took action in December 1895. Lenin was arrested and so were other Marxist activists, his colleagues from the League of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class. Lenin after a period of detention was exiled and sent to Siberia where later he was joined by Nadezhda Krupskaya his fiancée, a committed Marxist herself who later became his wife. During the four years in exile he produced thirty works of political theory and it was during this time that he is said to have clarified and consolidated his political thinking.

- One of the founders of the first Marxist organisation in Russia: the Emancipation of Labour group.

- The World in Arms, History of the World, Time-Life Series, p. 55.

- Earlier the group was known as the Social Democrats.

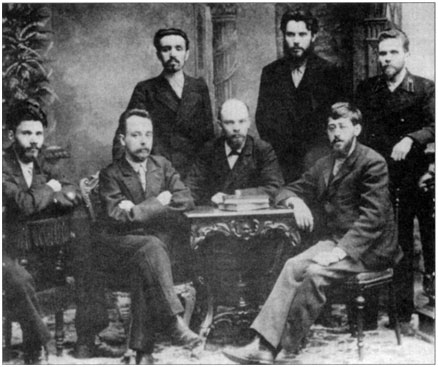

The leaders of the Petersburg League of Struggle for the Liberation of the Working Class. Seated behind the table: Lenin. The picture was taken when they were released from prison before being sent to Siberia.

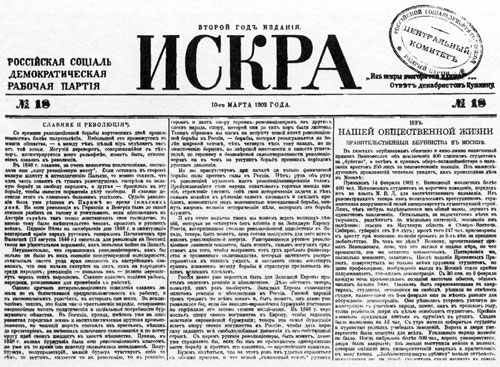

After his release from exile, Lenin fled to Western Europe, living in Germany, England and then Switzerland. In 1900, Lenin felt strongly the need of a Marxist newspaper and the formation of a political party; both could be used as vehicles to overthrow the Tsarist regime. He was a marked man in Russia under the constant surveillance of the Okhrana1 (the Russian secret police) and so had to base his publishing activities in Europe. He joined other leading exiled Marxists, Plekhanov and Martov, in starting a newspaper called Iskra, or The Spark,2 to expound their thinking and develop

1. An acronym for The Department for the Protection of Order and Public Security.

2. Its motto was taken from the Decembrists' reply to the poet Pushkin: "From the spark a flame will be kindled."

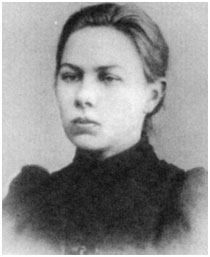

Nadezhda Krupskaya in 1895

their ideas, and which they hoped would unify under- ground Russian Marxist groups which were scat- tered throughout Russia and western Europe, into a Social- Democratic party. The idea was that a newspaper would be the best way to build the party, and develop the core of party thought. To avoid imprisonment by Russian authorities, he was forced to print the paper in European countries. Iskra would go on to become the most successful underground publication, smuggled into Russia illegally. It contained contributions from many known figures of Marxism all over Europe and in 1902 regularly from the young Ukrainian, Leon Trotsky. During these years of travel Lenin maintained close contacts with other revolutionaries in exile. Between 1893 and 1902, Lenin began to revise his understanding of Marx, the essential features of which would be called in later years, Leninism. His idea was that a class consciousness had to be developed among the masses by making them politically aware, by a well organized revolutionary party with an elite leadership in the vanguard — the "vanguard of the proletariat", leading ultimately to the dictatorship of the proletariat.

In 1902, he brought out a booklet What Is To Be Done? which stirred up a huge controversy among the readers. "Give us an organization of revolutionaries," he exhorted in the booklet, "and we will overturn Russia!" This type of exhortation was new for the Marxists who till then were used to a more moderate approach.

For the people sympathetic to Lenin and his approach, this booklet "was his hymn to leadership." It conveyed his sense of urgency and his insistence that the great duty in politics was to lead the way. From then onwards, even though he would go on to write numerouspamphlets, articles, and books, What Is To Be Done? would be taken as Lenin's defining interpretation of Marxism, based on Russian conditions.We are told that:

He cheered and cajoled his fellow activists. He managed to let them know that, whatever difficulties they might be experiencing, he understood them — and yet he also expected them to produce wonderful results. `Miracles', he asserted, were within the range of attainment of Russia's Marxists. Too much rationality was no great thing: 'We've got to dream!' 1

While completing What Is To Be Done? he was also involved with other political tasks such as editing Iskra and getting a draft party programme ready in time for the Second Party Congress of The Russian Social Democratic Labor party (RSDLP), a party that he had just joined. It had been secretly formed at a congress at Minsk in 1898; based on the doctrines of Marxism, it had been formed to unite the various revolutionary parties. The task of preparing a draft party programme was a difficult and time-consuming task as Lenin differed on many points from his mentor, the prominent Marxian scholar and revolutionary, Plekhanov, for whom, till then, he had a great admiration as the founder of Russian Marxism. He was a pupil of Plekhanov and one of his most passionate supporters.

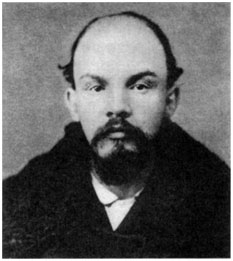

Vladimir Ulyanov in 1895. Picture taken by the police photographer

1. Robert Service, Lenin: A Biography, p. 141.

Plekhanov had written for Iskra when Iskra was founded in 1900 and along with Lenin supported proletarian revolution and attacked revisionism. However, Lenin wanted a programme that was suitable for a fighting political party. Though he and his followers wanted policy to be based on sound intellectual ground, uncompromising revolutionary action was of equal importance to them.

According to Leon Trotsky, one of the leading Russian revolutionaries — arrested for dissident activities while yet a teenager, he had not spent a single year on Russian soil as a free man — and a close associate of Lenin in later years, Lenin had:

... only one goal before his eyes, and towards this final goal he was pressing, whether in politics or in his theoretical or philosophical studies, in discussions with others or in learning foreign languages. His was perhaps the most determined utilitarianism ever produced in the laboratory of history... [Lenin's] whole being geared to one great purpose. He possessed the tenseness of striving towards his goal.1

He says further:

Lenin went abroad neither as a Marxist 'generally speaking', nor in order to devote himself to some 'general' literary-revolutionary work, nor for the purpose of carrying on the twenty-year-old activities of The Emancipation of Labour*. No. he went as a potential leader, as the leader of the revolution which was welling up, which he sensed and perceived. He went in order to build, in the shortest possible time, an ideological base and an organizational framework for that revolution. When I spoke about Lenin's tense concentration on his goal — concentration which was both passionate and disciplined — I did not see it as an effort to achieve a

1. Leon Trotsky, On Lenin, pp. 11-12.

* A Russian Marxist group

`final triumph', no, that would have been too vague and meaningless; I saw it as a concrete, direct, immediate work towards the practical aim of speeding up the outbreak of the revolution and of securing its victory.1

In 1903, Lenin attended the Second Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party (RSDLP), held in Brussels and then in London, which had been organized in an attempt to unite the party, to create a 'united force. However, it was an event that would lead to a split within the party. Should the party comprise activists (as Lenin urged) or have a broader membership? This was the issue, and Lenin argued forcefully for a streamlined party leadership group, one that would lead a network of lower party organizations and their workers.

Among all these varied tendencies and attitudes assembled under the banner of Iskra, which found their reflection in the editorial team, Lenin was the only one to personify the future: its grave tasks, its cruel struggles and innumerable victims. Hence the vigilance and suspicion of a combatant... Lenin began the task of sifting the cadres anew in a more stern and exacting manner.2

He believed that capitalism would only disappear with a revolution, not with gradual reforms, and that revolution was only possible under certain conditions; the revolution, to be followed by a dictatorship of the proletariat as the first stage of moving towards communism, and the need for a vanguard party to lead the proletariat in this effort. The party was split between Lenin's group called henceforth the Bolsheviks (Bolsheviki or majority group), and the group led by Martov, called the Mensheviks (Mensheviki or minority group), over the issue of "reformism". The Mensheviks were more focused on changing Russia peacefully through an evolutionary process, while the Bolsheviks wanted revolutionary change. Lenin's group

- Leon Trotsky, On Lenin, p. 64.

- Leon Trotsky, Ibid., p. 66.

remained in the majority for a very short while, but he kept the name and developed a disciplined, revolutionary group. His brainchild Iskra, which had been his life for three years, had now to be relinquished to the Mensheviks who took control, unwilling as he was to serve under them; there was an unbridgeable gap between his own unwavering determination and the other group's lack of political will. His break with his former colleagues done in the 'best interests of the revolution' brought him a great deal of criticism and he made enemies by what was seen as scant respect for the old guard. His uncompromising stand was viewed by many as "intransigence and ruthlessness — though he would call it revolutionary purity..."1 A year and a half later he would launch his own newspaper called Vpervod (Forward).

Leon Trotsky, who after his escape from Siberia had worked with Lenin on the revolutionary newspaper Iskra, in London, was initially a supporter of the Menshevik Internationalists faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party before joining Lenin's Bolsheviks at a later period. He has commented on this event in the following words:

To take such a step facing the opposition of half the assembly, having Plekhanov as a doubtful semi-ally and all the other members of the editorial staff as determined opponents; to embark in such conditions on a work like this, one had to have faith not only in the cause but also in one's own strength.

This faith in his own strength was the result of Lenin's self-evaluation tested in practical experience. He acquired it also during the work with the 'masters' and through the first skirmishes — already then there were sparks flying and flashes of lightning portending the thunders and the tempests of the coming rupture. It was Lenin's impressive singleness of purpose which allowed him to embark upon his task and to conclude it.

1. Helen Rappaport, Conspirator: Lenin in Exile, p. 96.

Tirelessly, he was tightening the string of his bow more and more, to the limit — quietly testing: was there no flaw? no danger that it would snap? From all sides he heard warnings: do not make it any tauter, don't!

"It will not snap," answered the master archer, "our bow is made of unbreakable proletarian stuff, and the string has to be tightened more and more, for the arrow is heavy and we have to launch it far, very far into the distance."1

The revolutionary newspaper Iskra

The revolutionary newspaper Iskra

1. Leon Trotsky, On Lenin, pp. 66-67.

Left: A Russian warship before meeting the Japanese.

Left: A Russian warship before meeting the Japanese.

Russian protected cruiser Oleg, showing battle damage after the Battle of Tsushima where the Russian fleet was annihilated by the Japanese

Russian protected cruiser Oleg, showing battle damage after the Battle of Tsushima where the Russian fleet was annihilated by the Japanese

Related Books

- Alexander the Great

- Arguments for The Existence of God

- But it is done

- Catherine The Great

- Danton

- Episodes from Raghuvamsham of Kalidasa

- Gods and The World

- Homer and The Iliad - Sri Aurobindo and Ilion

- Indian Institute of Teacher Education

- Joan of Arc

- Lenin

- Leonardo Da Vinci

- Lincoln Idealist and Pragmatist

- Marie Sklodowska Curie

- Mystery and Excellence on The Human Body

- Nachiketas

- Nala and Damayanti

- Napoleon

- Parvati's Tapasya

- Science and Spirituality

- Socrates

- Sri Krishna in Brindavan

- Sri Rama

- Svapnavasavadattam

- Taittiriya Upanishad

- The Aim of Life

- The Crucifixion

- The Good Teacher and The Good Pupil

- The Power of Love

- The Siege of Troy

- Uniting Men - Jean Monnet