Alexander the Great - Alexander as a General

Alexander as a general, leader of men and king of Asia

When Alexander died, he was not yet thirty-three. He was carried off at the very height of his youthful vigour, like his ancestor and model Achilles.1 He had not completed the thirteenth year of his reign. A retrospect of his gigantic life work brings before us a personality of quite unique genius, a marvellous mixture of demonic passion and sober clearness of judgement. In this iron-willed man of action, who was a realist in policy if anyone ever was, beneath the surface lay a nonrational element: for example, his 'longing' for the undiscovered and the mysterious, which, coupled with his will to conquer and his delight in scientific discovery, sent him to the limits of the known world. (...) He was firmly persuaded that he was under the special protection of the gods, and therefore

_______________

1 Achilles in Greek mythology, son of the mortal Peleus, king of the Myrmidons, and the Nereid, or sea nymph, Thetis. He was the bravest handsomest, and greatest warrior of the army of Agamemnon in the Trojan War. During the first nine years of the war, Achilles ravaged the country around Troy and took 12 cities. In the 10th year a quarrel with Agamemnon occurred when Achilles insisted that Agamemnon restore Chryseis, his prize of war, to her father, a priest of Apollo, so as to appease the wrath of Apollo, who had killed many in the camp with a pestilence. An angry Agamemnon recouped his loss by depriving Achilles of his favourite slave, Briseis. Achilles refused further service, and consequently the Greeks floundered so badly that at last Achilles allowed Patroclus to impersonate him lending him his chariot and armour. Hector (the eldest son of King Priam of Troy) slew Patroclus, and Achilles, having finally reconciled with Agamemnon, obtained new armour from the god Hephaestus and slew Hector After dragging Hector's body behind his chariot, Achilles gave it to his father Priam at his earnest entreaty.

Believed in his mission. It was said that: "This sense of divine possession is characteristic of the conduct of the great men of antiquity;" that is true of no one more than Alexander. (...) This firm belief in his mission gave him an absolute confidence in victory, without which his will and actions would be unintelligible. The supernatural in his temperament gave him also control over men.

The general and the statesman are indissolubly bound up in Alexander; as a general he was the executor of his political will. The general is easier to comprehend, since we have finished performances to survey, whereas the tasks of the statesman were still in process of evolution when he died. Alexander is the type of the royal general, who has unlimited control over the military material and apparatus of his country and is responsible to himself alone. He had no trials for conduct in the field to fear, such as the Athenian democracy loved, and no need to whitewash himself. (...) He had further the good

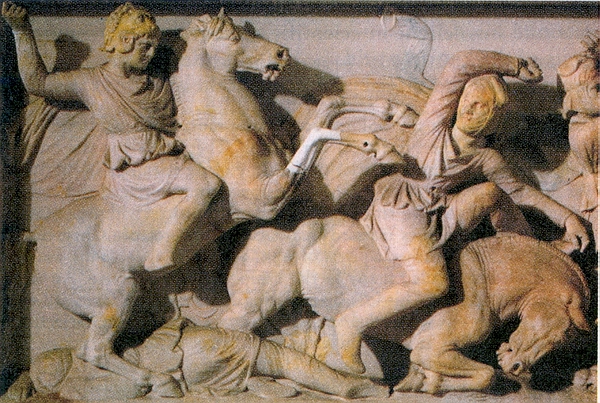

Alexander in battle (detail of sarcophagus sculpture)

Fortune to inherit the best army in the world at the time, together with a tried body of officers, and to have been initiated into the art of war by his father, who was himself a great general. These fortunate conditions made it easier for him fully to develop his military genius, but the important point was that this genius was born in him. (...) Military experts in ancient as in modern times agree that Alexander as a general was as great a genius as any in history.

As a tactician we saw him fight and win the three great battles, theGranicus,IssusandGaugamela,by the tactics developed by his father. But only the tactical idea was common to them. Its execution in detail Alexander varied according to the peculiarities of the ground and of the enemy. (...) Completely different was the set of problems he had to solve in the terribly difficult guerrilla war in Eastern Iran. Here we have a still more brilliant exhibition of his independence of his father's tradition in his operations with flying corps and his adaptation to the different mode of warfare of the new enemy. The severe fighting in the mountainous region north of Kabul, and especially the capture of Aornos, display Alexander in all his greatness. Perhaps the most signal stroke of genius is to be seen in his last great field of battle on the Hydaspes, when he had to deal with the totally new problem presented by the huge elephant host of Porus.

His strategic genius we saw from the beginning in his plan for the Asiatic campaign, according to which, on account of the difficult situation in Greece, he resolved first to win the Mediterranean coasts of the Persian empire with his land army in order to eliminate the superior Persian fleet. We saw with what tenacity and how in spite of all temptations he pursued this plan, up to the conquest of Egypt, and how thus he actually became master of the sea. When he led his army into the interior of Asia he faced new problems. Up to the Euphrates the march of the Ten Thousand had made all clear. What lay beyond the Euphrates was completely unknown country. So it was into mysterious distances that Alexander led his army, overcoming

All natural obstacles, over the snowy Hindu-Kush and over broad rivers, and finally through the Punjab to the Hyphasis, where the rnorale of his troops gave out and he turned round.

Yet the; re is nothing adventurous in his march. On the one hand, always and from the beginning he tried to get advance information about the foreign country which he wished to conquer, cook care, as far as was possible, to be enlightened by his spies about political, military and local conditions, and as a result entered into alliances with individual rulers by clever diplomacy, as before his Indian campaign, or sent out voyages of exploration, as before the Arabian expedition. On the other hand he never advanced without having covered his rear. (...) When he made his first conquests in Asia, he began at once to secure the conquered territories from the military point of view, and to ensure peace and order by administrative arrangements. Later when he penetrated into the heart of Asia, and went ever to more remote countries, he followed the same principle, and thus in spite of the tremendous distances, which finally he put between himself and home, he succeeded in never losing connection with it. Only once, at Issus, was he, by an unusual chain of events, cut off from his base of operations, yet in a few hours he carved his way out of the dangerous situation. "What proves his systematic method is that even in the Far East the drafts1 for his army from Macedonia and Greece always reached him according to his directions. This was only possible because he deliberately and most carefully built up a system of rest stages. Without such measures his successes and his triumph over distances, which our military experts often admire more than his battles, would not be conceivable. (...)

Among Alexander's great qualities as a general is the tenacity "with which, when he once regarded anything as essential, he carried it out to the bitter end. He lay seven months before Tyre, till he had got hold of it. (...)

He showed himself, too, a great leader of men, by participating

___________

1 Draft: detachment of military personnel from one unit to another.

In all the dangers and fatigues of his troops; in this way he carried them along with him. In battle he set them an example of supreme personal bravery; on the march there were no toils1 he did not share. If in sieges causeways or anything of the kind had to be constructed, he himself took a hand in the task, praised those who succeeded, and punished those who failed. When outstanding successes had been gained, he liked to reward his troops, by holding games and all sorts of festivities for them. His extensive money gifts to his army were a compensation for the prohibition of plundering the conquered districts, which for political reasons he thought necessary. This presupposes strict discipline. By the humanity with which after battles he cared for the wounded, he won the hearts of his soldiers. To his Macedonian officers he preserved to the end the attitude of a comrade. Though not imposing in figure, for he scarcely reached middle height, he dominated everybody by his wonderfully bright eyes. The towering nature of his personality is most clearly exhibited in the fact that the men nearest to him, who after his death in many cases showed themselves to be strong rulers, blindly obeyed him during his lifetime.2 Nearchus says once, with reference to the beginning of his-ocean voyage, that the army believed in Alexander's wonderful luck, and was of the opinion that there was nothing he could not dare and do. It was that mystical faith of an army in its leader, which Caesar also and later Napoleon were able to evoke.

It is more difficult to understand or even to judge the statesman in Alexander than the general; for his views as a statesman were in a state of flux,3 when he was called away by an early death. None of his political creations had as yet taken definitive shape, and new plans were constantly emerging from his restless brain. It is impossible to conceive how different the world would have looked, if he had lived only ten or twenty

________

1 Toil: hard or exhausting work.

2 Cassender, son of Antipater, when king himself, shuddered at the sight of a statue of Alexander at Delphi.

3 Flux: state of continuous change, fluctuation.

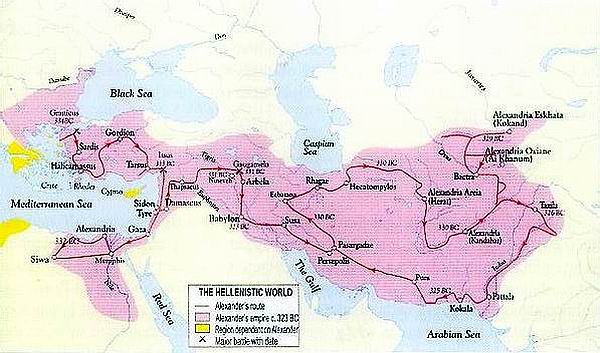

Alexander's empire

Years longer. How differently then should we be able to judge the youthful work which he did up to 323. We must never forget that we have only beginnings before us.

Let us now examine his behaviour as King of Asia. The use of Darius' seal confirms the view that after the death of Darius Alexander felt himself to be his legitimate successor; henceforth on principle he regarded the Asiatics no longer as his enemies but as his subjects. Starting from this, he reached the thoroughly statesmanlike conviction that he must enlist the vigour contained in these nations for the great problems that Asia presented to him. This course commended itself the more as it was to be hoped that it would have a reconciling and calming influence on the subjected peoples. (...) A still more urgent necessity was the recruiting of his army with the elite troops of Asia, for his European troops were insufficient for the colossal plans he was revolving in his brain. The filling up of gaps with Asiatic forces was absolutely imperative from the military point of view. Here, as in the administrative posts, he chose Iranians especially Persians, and after the court quest of Eastern Iran its inhabitants too. (...)

He did not, however, stop at the use of Iranians in the administration and the army, a use which will be recognised as politically right and required by circumstances, but went beyond it to the idea of a race-fusion of his Macedonians with these Iranians, an idea which dominated him more and more, as we saw, in his last years. He himself set the example by his marriage with Roxane (327), and later by the mass-marriage of Susa (324) he expressed most plainly his political intentions. Obviously he regarded this fusion as a means to an end; his aim was to build a bridge between the Macedonians, who were increasingly dissatisfied with the military employment of the Persians, and these same Persians, and to restore concord and agreement between the two peoples, so that hand in hand they might afford a sufficient guarantee against possible hostile reactions on the pan of other nations of the empire. Thus conceived, the policy of fusion may be regarded as a statesmanlike

Idea, however surprising the thought of race-breeding promoted by government may appear, and however doubtful it is whether such a fusion as Alexander desired was at all feasible, and finally, whether it would have had the effect for which he hoped. (...)

In the "Prayer of Opis"1 Alexander expressed very clearly the conception he held of his monarchy over Asia and his policy of reconciliation, when at the great feast of union he prayed to the gods that concord and partnership of rule might be granted to the Macedonians and Persians. As the Macedonians alone were insufficient for the ruling of Asia, the previously dominant Persians, who already under the Achaemenids2 had taken up a privileged position before the other nations of the world empire, were to be called to the leadership along with them. Alexander's Asiatic empire — for only to this can his words refer — was thus to become a Macedonian-Persian empire. In this ideal, only to be brought about by concord, he seems to have seen the best guarantee for the security and permanence of his Asiatic empire, and his civilising policy. (...)

We see Alexander too as an economist who knew what he was aiming at. He founded numerous cities, which were able and were intended to be the props3 of distant traffic. His most magnificent foundation, Alexandria in Egypt, was from the

________________

1 In 324 Alexander's decision to send home Macedonian veterans under Craterus was interpreted as a move toward transferring the seat of power to Asia. There was an open mutiny involving all but the royal bodyguard; but when Alexander dismissed his whole army and enrolled Persians instead, the opposition broke down. An emotional scene of reconciliation was followed by a vast banquet with 9,000 guests to celebrate the ending of the misunderstanding and the partnership in government of Macedonians and Persians but not, as has been argued, the incorporation of all the subject peoples as partners in the commonwealth. Ten thousand veterans were now sent back to Macedonia with gifts, and the crisis was surmounted.

2 Also called Achaemenid, Persian Hakmanishiya (559-330 B.C.), ancient Iranian dynasty whose kings founded and ruled the Achaemenian Empire. The dynasty became extinct with the death of Darius III, following his defeat (330 BC) by Alexander the Great.

3. Prop: support.

First designed to be an emporium. Even among the new cities in the Far East were many whose position on the old trade routes shows that they were designed to serve trading purposes; and so some of them are prosperous at the present day, like Herat,1 Kandahar2 and Khojend.3 He opened new sea routes for trade: the voyage of Nearchus connected his new colonial territory in India with Babylon; he himself intended shortly before his death to connect Babylon with Egypt by an expedition by sea around Arabia; he rendered the Tigris navigable, and a "new Phoenicia" was designed on the coast of the Persian gulf; great harbour works were begun in Pattala and Babylon for the pro- motion of navigation and trade. All these are achievements and designs of colossal dimensions, which display a genius at work, who intended to divert into the paths he regarded as right the world commerce of his world-empire. (...)

Finally we come to his civilising policy. Alexander marched out as the enthusiastic admirer of Greek culture who was to open up the East to its influence. Did he remain faithful to this object after he had become acquainted with the old cultures of the East, which could not fail to impress his susceptible4 nature? Was he still faithful after the idea of a fusion of the nations had laid hold upon him in his last years with ever-increasing force? One thing is undeniable: in spite of all Iranian policy he was personally to the last an enthusiastic admirer of Greek culture. The pupil of Aristotle never abandoned the idea of making his triumphal march also a journey of discovery, and of causing it to serve Greek science through the examination of lands hitherto unknown by the staff of experts who accompanied him. Out of the later years we need only call to mind the zealous work of investigation in India, Nearchus' voyage of exploration, and finally the mission of Heraclides to the Caspian Sea. (...)

___________

1 In western Afghanistan.

2 In south-central Afghanistan.

3 Modern Leninabad.

4 Sensitive, impressionable.

His love of Greek literature remained unchanged to the end. He started out with Homer, and later he sent from the Far East for other works of literature, classical and modern. He had special veneration for the three great tragedians, above all for Euripides, whom he knew so well that at times he could recite entire scenes from memory. Besides the poets who accompanied his travelling court there were also in his camp philosophers and philosophically educated men of the most different schools. (...) The intellectual life at the court of Alexander, which we picture as very animated, was thoroughly Greek. So far as we know, he had no acquaintance with the literatures of the Oriental peoples. (...)

Greek art too remained for him the art. We never hear that he caused Oriental artists to work for him; on the contrary he exclusively employed Greeks. His architects also were Greeks. (...)

But nothing actually had so strong an effect on the Hellenisation of the East (so far as one can speak of anything of the kind) as Alexander's foundation of cities. (...) The colonists settled in these cities were chiefly Greek mercenaries, many thousands of whom were left behind in these spots, along with a lesser number of Macedonians, probably veterans for the most part. As these mercenaries to a great extent came from an uprooted proletariat1 (...) one may regard Alexander's city-foundations as a solution on a grand scale to a social and economic problem. (...) These cities received from him a Greek constitution: a council, popular assembly and city magistrates. In spite of this they seem not to have possessed complete autonomy, and in all likelihood were directly under the king.(...)

At the time of the foundation of the cities in Eastern Iran Alexander had already conceived the idea of bringing the Iranians into closer relation with the Macedonians and Greeks, and soon afterwards he was busy with the fusion of these

__________________

1 Proletariat: the lowest social class in any community.

Peoples. The prospect therefore of a gradual mixture of cultures in the settlements cannot have run counter to the views which he then held. Was he thus unfaithful to his original object of spreading Greek culture in the East? Personally, in spite of all the political concessions which he made to the Iranians, he remained to the last, as we saw, a thorough admirer of Greek culture, and it must accordingly still have been his ambition to make Greek culture prevail as far as possible. But just as he had learned as a politician that he could not rule his Asiatic Empire with Macedonians alone, so in active contact with Oriental cultures it must have become clear to him that neither could he make Greek culture exclusively dominant. The chief requisite was that centres should at first be created from which the spread of Greek culture could take its start — and that is what he accomplished by the cities which he founded. Though mixtures of culture might be expected later, vet in his attitude to Greek culture he must have had the desire and confident expectation that it would be the leading factor. The great question of the future in fact was, which of the two cultures would prove itself the stronger. For many centuries this was the chief problem of the history of civilisation. (...)

Taken from:

Alexander the Great by Ulrich Wilcken Translated by G.C. Richards W.W: Norton and Company

Related Books

- Alexander the Great

- Arguments for The Existence of God

- But it is done

- Catherine The Great

- Danton

- Episodes from Raghuvamsham of Kalidasa

- Gods and The World

- Homer and The Iliad - Sri Aurobindo and Ilion

- Indian Institute of Teacher Education

- Joan of Arc

- Lenin

- Leonardo Da Vinci

- Lincoln Idealist and Pragmatist

- Marie Sklodowska Curie

- Mystery and Excellence on The Human Body

- Nachiketas

- Nala and Damayanti

- Napoleon

- Parvati's Tapasya

- Science and Spirituality

- Socrates

- Sri Krishna in Brindavan

- Sri Rama

- Svapnavasavadattam

- Taittiriya Upanishad

- The Aim of Life

- The Crucifixion

- The Good Teacher and The Good Pupil

- The Power of Love

- The Siege of Troy

- Uniting Men - Jean Monnet